Pompeii (26 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

Yes – or, at least, up to a point. The zebra stripe design is very obviously associated with the service quarters. It is true that there are one or two more upmarket rooms in the town decorated in this style, but by and large this was the cheap wall decoration slapped onto latrines, slave rooms, utility areas and corridors (the ancient equivalent of a quick coat of white emulsion). We have also seen that the walls of a garden would often be decorated with themes which picked up the idea of verdant foliage, and hinted at an imaginary wilderness (populated by beasts, pygmies and other exotic figures) stretching in the mind’s eye far beyond the confines of the house. It is significant too that those parodies of well-known myths, treated with all due seriousness in most other paintings in Pompeii, are found in a private bath suite. For baths were a place of pleasure where social norms were relaxed, as is signalled in the House of the Menander by the mosaic on the floor at the entrance to the ‘hot room’: a dashing and scantily clad black slave, garland on his head, carrying two water flasks which rhyme in colour and shape with his (large) penis; underneath an arrangement of four strigils (oil scrapers) and a jar on a chain which is also decidedly phallic (Ill. 52).

But we can trace a few more-general links between the use of different areas of the house and the decoration on its walls, its colours and themes. In the modern Western home, pastel colours regularly signal bedrooms or bathrooms. In Pompeii, the householder often seems to have chosen black background paint for his grandest rooms, cheap though the basic ingredient of that paint could be (Pliny, interestingly, refers to various more-expensive black pigments, including one imported from India). Yellow and red were relatively high-status alternatives.

52. The mosaic floor at the entrance to the hot room in the House of the Menander. An almost naked black slave displays his large penis, while underneath the strigils used by bathers for scraping off the sweat and grease are arranged in a matching phallic pattern. What message was this for the naked bathers?

To judge from the cost and from the comments of Roman writers, one very special red pigment, cinnabar or vermilion (‘mercury sulphide’ to a scientist), which was mined in Spain, was the very height of luxury. This was so sought after that, according to Pliny, a maximum price was set by law (just over twice the price of Egyptian blue), to keep it ‘within limits’. He also notes that it was one of a small number of expensive colours which were usually paid for by the patron separately, over and above the standard contract price for the job. It’s not hard to imagine how those negotiations might have gone: ‘... well, of course, I

could

do it in cinnabar, sir, but it’d cost you. It’d have to come as an extra. You’d probably be better getting hold of some yourself ...’ Negotiations between client and builder may not have changed very much over the centuries.

Not only a very desirable shade of red, cinnabar was also tricky to handle (no doubt part of its allure). For in certain conditions, particularly in the open air, it rapidly discoloured, turning a mottled black, unless a special coating of oil or wax was applied. As if to drive the point home, Vitruvius tells the story of a lowly but rich ‘scribe’ in Rome who had his peristyle painted with cinnabar and it had changed colour within a month. It served him right for not being better informed was the moral. The work being done in the House of the Painters at Work was not in the cinnabar range. But that pigment has been discovered in two of the obviously most prestige decorative schemes in Pompeii: the Villa of the Mysteries frieze and one of the rooms off the peristyle in the House of the Vettii.

Different decorative styles also pointed to different functions or different levels of exclusivity with the house. The fact that the First Style is most often preserved in domestic atria and that it continued in use in public buildings in the town is probably no coincidence. Within the domestic sphere it came to signal public areas of the house. Likewise (though this argument is perhaps rather too circular for comfort) you can often spot rooms, large or small, that were intended to impress the invited guest by their concentration of mythological paintings, almost as if in an art gallery, and by their extravagant architectural vistas. One scholar has even suggested a simple rule of thumb, which works well enough for Second and Fourth Styles at least: ‘the greater the depth suggested by the perspective effects, the higher the prestige of the room.’

So decorative choices for the Pompeian householder came down to a trade-off between fashion and function. This was true right across the social spectrum. For, as we saw with the overall architecture of the house, there is no sign of any particular difference in taste, or in the underlying logic of their decor, between the properties of the rich and those of modest means, or between those of the old elite families and rich ex-slaves. Even if the houses of the poor had no public role, the householders followed the same cultural norms of decoration so far as they could afford it. And, despite many attempts by modern archaeologists to sniff out the vulgarity of the Trimalchio-style nouveaux riches, it has usually been more a projection of their own class prejudices than anything else. In the end, the differences between the paintings in rich and poor houses come down to not much more than this: the poor had fewer figured scenes, fewer dramatic extravaganzas of design and no cinnabar, and (notwithstanding a few second-rate daubings in elite properties) the quality of painting in their houses was generally much cruder. Pompeii was a town where you got what you paid for.

Myths do furnish a room

When the eighteenth-century excavators first discovered the paintings of Pompeii, it was the figured scenes in the centre of many of the Third and Fourth Style walls, not the extravagant or whimsical architectural fantasies, that caught their imagination. For these were the first visual representations of ancient myth ever to be discovered in such quantity. What is more, they offered a first glimpse of the lost tradition of painting which Pliny and other ancient writers hyped as one of the highlights of ancient art. True, Pliny was usually referring to masterpieces of easel painting by famous Greek artists of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, prize possessions of temples and monarchs; and these were panels painted directly onto the wet wall plaster of domestic housing in a small Roman town. But, in the absence of the original works by Apelles, Nicias, Polygnotus and the others, they were the best evidence available. Many of the most striking examples were cut out of the wall on which they were found and taken to the nearby museum – where, of course, they came to resemble ‘gallery art’ even more closely.

The range of myths chosen by the painters and their patrons is very wide. There are, it is true, some puzzling absences. Why, for example, so few traces of the myth of Oedipus in Pompeii? But some of the themes of Pompeian painting are old favourites for us too: Daedalus and Icarus, Actaeon accidentally (but disastrously) catching sight of the goddess Diana at her bath, Perseus rescuing Andromeda from her rock, the self-regarding Narcissus, and a variety of familiar scenes from the story of the Trojan War (the Judgement of Paris, the Trojan Horse and so on).

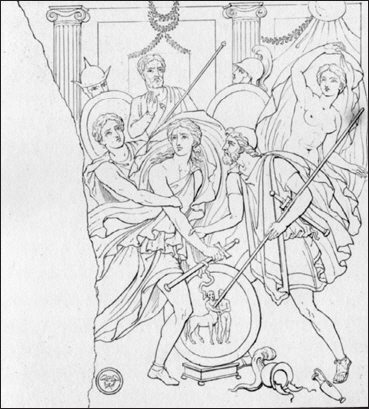

Others, though obviously favourites in Pompeii, are to us rather more arcane. No fewer than nine similar paintings have been discovered depicting a tale which came to be told as a ‘prequel’ to the Trojan War: Achilles on the island of Skyros. At first sight their subject looks like any other heroic brawl. But there is a curious back story. The Greek hero has been hidden away by his mother Thetis to keep him out of the conflict; he is disguised as a woman and lodged with the daughters of Lycomedes, the king of the island. Knowing that Troy can only be taken with Achilles’ help, Odysseus arrives disguised as a pedlar and succeeds in ‘outing’ him with a cunning ruse. When he lays out his wares – trinkets, ornaments and an assortment of weapons – the ‘real’ girls go for the ornaments, while Achilles reveals his manhood by choosing the weapons. Odysseus, as we see here (Ill. 53), takes that as his opportunity to pounce on the renegade.

53. A tale of cross-dressing – and a favourite theme of Pompeian painting. Achilles, in the centre, is in hiding from the Trojan War, dressed as a woman and living among the daughters of the king of Skyros. But he is ‘outed’ by Odysseus, who grabs him from the right, to take him back to do his duty as a warrior.

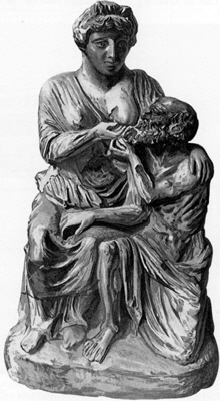

An even stranger story appears in at least four paintings, plus a couple of terracotta statuettes (Ill. 54). It is the image of one of the most extreme forms of filial piety imaginable. An old man, Micon, has been imprisoned with no food and risks dying of starvation. He is visited, so the legend goes, by his daughter, who has recently had a baby. To keep her father alive, she feeds him with the milk of her breast. In one version, in the House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto (so called after the likely owner), the scene is explained and the message is underlined by some lines of poetry, painted next to the figures: ‘Look how in his poor neck the veins of the old man now pulse with the flow of the milk. Pero herself caresses Micon, face to face. It is a sad combination of modesty [

pudor

] and a daughter’s love [

pietas

]’. A superfluous explanation perhaps. For paintings of this story were notorious at Rome for their visual impact: ‘Men’s eyes stare in amazement when they see what is happening’, in the words of one roughly contemporary Roman writer.

54. A devoted daughter feeds her imprisoned father. This myth of filial piety caught the imagination of the Pompeians. Here it is represented in a terracotta figurine. Elsewhere it provides the subject for paintings.

Why so many versions of the same scene? Almost certainly, in some cases, because they were inspired by the same famous old master of Greek art. The archaeologists of the eighteenth century were not entirely wrong when they imagined that the paintings in Pompeii might give a glimpse of lost Greek masterpieces, faint as it might be. Occasionally, in fact, there are tantalising similarities between the images on these walls and the descriptions of much earlier paintings given by Pliny and others.

One of the best-known panels from the House of the Tragic Poet, for example, shows the sacrifice of the young Iphigeneia by her father Agamemnon before the Greek fleet sailed for the Trojan War – an offering to the goddess Artemis in return for fair winds (Ill. 55). The almost naked girl is being carried to the altar while her father, distraught at his own deed, covers his head in sorrow. This is exactly how both Pliny and Cicero describe a painting of the sacrifice of Iphigeneia by the fourth-century BCE Greek painter Timanthes: ‘the painter ... felt that Agamemnon’s head must be veiled, because his intense grief could not be represented with the paint brush.’ But, as a whole, what we see at Pompeii was nowhere near an exact copy of Timanthes’ masterpiece, in which Odysseus and the girl’s uncle Menelaus also featured, and Iphigeneia, rather than being carried as she is here, stood calmly by the altar awaiting her fate. There seems a fair chance too that some of the scenes of Achilles among the women of Skyros go back ultimately to a famous easel painting by one Athenion: ‘Achilles concealed in girls’ clothes when Ulysses [i.e. Odysseus] finds him out’, as Pliny briefly describes it; though the differences in detail from one Pompeian version to the next suggest again that they are variations on the theme, not exact copies of the original.