Secondary Schizophrenia (147 page)

Read Secondary Schizophrenia Online

Authors: Perminder S. Sachdev

but quite clear and occurred in overlapping sequence

with damage to the occipital lobe may

[62]

or may

A

→

B

→

C over a period of 10 to 12 days.

not

[19,

63]

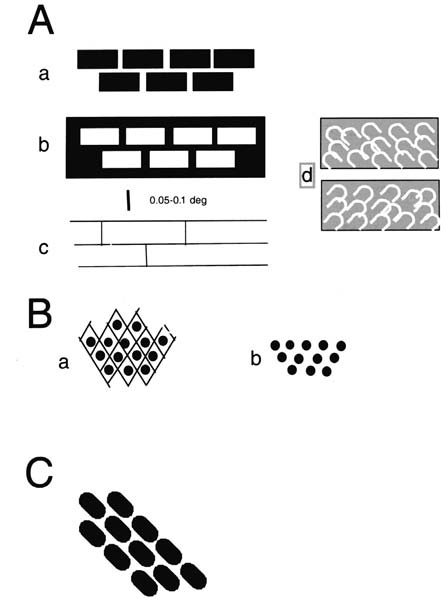

show epileptiform discharges. Neverthe-When the primate visual area V1 is stained for

less, it has been repeatedly shown that isolated cortex

cytochrome oxidase, it is characterized by orderly rows

becomes epileptogenic

[64, 65].

of “blobs” with an arrangement both qualitatively and

A further elaboration of these ideas is to sug-

quantitatively similar to that of the “spots” shown in

gest that the more extensive the damage to the visual

Figure 30.2B.

Similarly, when visual area V2 is stained,

system, the higher in the visual hierarchy does the

it reveals an arrangement of stripes closely resem-

increased spontaneous activity extend and the more

bling in dimensions the brickwork shown in Figure

likely it is that the hallucinations will be complex.

30.2A. Cytochrome oxidase is an indicator of high

Leaves and branching structures might be located

371

metabolic rate and might be expected to signal the

higher than brick walls; people and buildings would be

Related Concepts – Section 4

is this second model, which is appropriate for CBS,

and which I will explore in detail. Simply stated, the

deafferentation theory proposes that deafferentation

leads to hypersensitivity at the deafferented synapses

and this leads to increased spontaneous activity that is

the neural basis of the hallucinations. The fact that low

contrast sensitivity is a strong risk factor for CBS also

supports this theory

[72].

The deafferentation syndrome model has been

most successful when applied to the somatosensory

system, the best example being the “phantom limb”

phenomenon. When a patient loses a limb, the neurons

in the cerebral cortex that normally receive input from

the limb are still there and undamaged. Therefore, if

by any means they are excited, they will signal that the

limb is being touched or stimulated in some way. It

is irrelevant how the cortical neurons are excited; as

a result of deafferentation, they are likely to become

spontaneously active and this activity will create the

phantom. The theory was probably even more success-

ful in explaining the anomalies in pain sensation, for

example, how pain can be increased when the number

of pain receptors is decreased

[73].

Deafferentation in

the auditory system can lead to tinnitus and hallucinations

[74, 75, 76].

Occasionally, a combination of visual

Figure 30.2

Sketches of portions of hallucinations seen by the

and hearing loss leads to both visual and auditory hal-author over a period of 10–12 days following a macular hole in each

eye. The hallucinations appeared in the sequence A, B, C with some

lucinations

[77].

The fact that hallucinations can occur

overlap. Those shown in Ad have persisted for several years and

in other sensory modalities in the absence of psychi-may be generated in the lateral geniculate nucleus where

atric involvement suggests that the term “CBS” might

reinnervation may occur less readily. (From

[60],

with permission.)

reasonably be applied to these occurrences also but this

is not the case at present.

in the highest regions. However, the evidence to date

Hallucinations could depend on a purely excita-

does not support this idea

[66, 67].

It may be that the

tory effect or there could be removal of a maintained

progression through the visual cortex from simple to

inhibition, a “disinhibition.” Cogan

[35]

classified

complex is dependent on the ability of the cortical neu-visual hallucinations into “irritative” and “release.”

rons to emit marked spontaneous discharges, and this

The former were compared to an “epileptic” or “ictal”

ability would vary in different individuals.

attack, whereas the latter was presumably a disinhibition. In fact, we do not usually have enough information to decide between these two alternatives or even

Theories of hallucination generation

to determine if they are alternatives. For convenience, I

There are two broad theories of hallucination genera-will concentrate on the purely excitatory model, always

tion

[68].

The first theory, the “Perception and Atten-remembering that other possibilities exist.

tion Deficit Model”

[69]

, proposes that there is both

Several synapses, some from the mammalian cen-

impaired attention and poor sensory activation and

tral nervous system, some from elsewhere, have been

the interaction between the two leads to hallucina-

studied in great detail under conditions in which the

tions. This model may be appropriate for the hallucina-inputs have been varied widely. There has been a large

tions of schizophrenia and some other hallucinations,

measure of agreement between the different reports.

although a case has been made out for a deafferentation

Total silencing of the input to a synapse leads to the

model here also

[70].

The second model emphasizes

following presynaptic changes: increases in the size of

372

the “deafferentation syndrome” aspect

[18,

68, 71].

It

the terminal bouton, in the total number of vesicles, in

Chapter 30 – The Charles Bonnet Syndrome

Table 30.1

Cortical areas with increased sensitivity to specific visual stimuli

Name of area

Acronym

Anatomy

Stimulus/function

Reference

Fusiform face area

FFA

Fusiform gyrus

Faces

Kanwisher et al., 1997 [84]

Parahippocampal place

PPA

Parahippocampal gyrus

Scenery

Epstein and Kanwisher, 1998 [85]

area

Superior temporal

STS-FA

Superior temporal sulcus

Movements of the

Perrett et al., 1982, 1995 [86, 87]

sulcus face area

eyes and mouth

Puce et al., 1998 [88]

Extrastriate body area

EBA

Lateral occipitotemporal

Whole body

Downing et al., 2001 [89]

cortex

Lateral occipital

LOC

Lateral and ventral occipital

Analysis of object

Kourtzi and Kanwisher, 2000 [90]

complex

cortex

structure

Visual word form area

VWFA

Left ventral occipitotemporal

Text

Cohen and Dehaene, 2004 [91]

sulcus

the number of docked vesicles, in the size of the release

parahippocampal gyri in the conscious patient causes

zone, in the size of the readily releasable pool, and

an awakening of memories of people, animals, and

in the release probability

[72].

Postsynaptically silenc-scenes

[42].

ing of the synapse causes “externalization” of synap-Second, functional magnetic resonance imag-

tic receptors that become “internalized” when synap-

ing (fMRI) from hallucinating patients has revealed

tic traffic increases

[79, 80, 81, 82].

The postsynaptic

increased activity in ventral temporal lobe, with one

membrane also shows greater electric excitability dur-patients hallucinating faces showing heightened activ-ing disuse of the synapse

[65].

All of these changes

ity in the fusiform gyrus of the ventral occipital lobe

point in the same direction: increased excitability

of the synapse during deafferentation. In certain

Lastly, in this general region, several areas have

conditions, this may lead to increased spontaneous

been delineated as containing neurons with increased

activity.

sensitivity to specific visual stimuli

(Table 30.1).

These

Most neurons in the visual system are binocu-

areas have been mapped using fMRI or positron emis-

lar. Therefore, these are deafferented only when the

sion tomography (PET) technology or direct recording

inputs from the corresponding parts of both eyes are

from individual neurons.

lost. However, most neurons in the lateral geniculate

The FFA seems to be the same as the area men-

nucleus are monocular, and in cortical area V1, there

tioned in the last-but-one paragraph and is probably

are monocular neurons activated only from contralat-

concerned with facial recognition, whereas the STS-

eral nasal retina. Before the extent of deafferentation

FA is more related to facial expression

[92].

The areas

can be judged, it is necessary to have a detailed knowl-described by Wicker and colleagues

[93]

as concerned

edge of the position and size of the lesion. This is sel-with gaze would have included STS-FA. Lesion of the

dom possible. When the damage is in the cerebral cor-VWFA causes alexia but may also lead to VHs con-

tex, the more anterior the lesion, the less likely will

sisting of grammatically correct, meaningful written

there be any hallucinations

[63];

this may be because

sentences or phrases

[94].

The patient cannot read but

the chance of deafferentation is less.

can hear and write correctly what she hears. There is

evidently an area in this region deafferented by the

Site of complex hallucinations

lesion in the VWFA, possibly the anterior fusiform

There is now evidence from separate types of study

area described by Nobre and colleagues

[95]

or part

strongly suggesting that complex VHs are generated

of the cortical area associated with auditory hallucina-in visual areas in the temporal lobe of the cerebral

tions because of the resemblance of the hallucinations

cortex and some adjacent regions. The evidence is

to those experienced by schizophrenics

[94].

threefold. First, electrical stimulation of the ven-

The conclusion from these three separate

tral superior, middle, and inferior temporal gyri; of

approaches is that complex VHs are closely asso-

373

the inferior parietal lobule; and of the fusiform and

ciated with increased activity in a region of cortex

Related Concepts – Section 4

extending from superior temporal cortex ventrally to

Prevalence and incidence

the parahippocampal gyrus and probably originate in

The published estimates are unreliable for several

one or other part of this region. There is no reason why

reasons:

this conclusion should not apply to all VHs, whatever

their etiology. However, each patient has a unique

1. There is no agreed definition of CBS.

pattern of hallucinations and it is not surprising that

2. The available data are derived from highly selected

these differ from the images created by the highly

populations of patients, for example,

abnormal electrical stimulation of the brain or from

ophthalmology clinics.

mental imagery

[52].

The view presented here is

3. Patients experiencing complex hallucinations may

radically different from that of Weinberger and Grant

not report them for fear of being treated as insane.