Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (11 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

13.18Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The retreat of Chinese residents from Idaho was especially striking. In 1870, Chinese made up one-third of the population of Idaho. By 1910, almost none remained. In the 1880s, assaults and murder became common practice. In 1886, white Idahoans held an anti-Chinese convention in Boise, and a mass movement against the Chinese spread throughout the state, growing even worse after statehood in 1890. Historian Priscilla Wegars tells that in 1891, “all 22 Chinese in Clark Fork were run out of town,” followed by Hoodoo the same year, Bonners Ferry in 1892, Coeur d’Alene in 1894, and Moscow in 1909. Chinese returned to some towns within a year or two but stayed out of Moscow until the mid-1920s and Coeur d’Alene until at least 1931.

11

11

Around this time, Chinese in California also came under attack. Democrats supported white workers’ attempts to exclude them. In May 1876, whites drove out Chinese from Antioch, California, one of the early expulsions, and in Rocklin the next year, they burned Chinatown to the ground. Expulsions and anti-Chinese ordinances peaked in the 1880s but continued for decades. In the 1890s whites violently expelled Chinese people from the fishing industry in most parts of the state. In all, between about 1884 and 1900, according to Jean Pfaelzer’s careful research, more than 40 California towns drove all their Chinese residents out of town and kept them out. Around 1905 came Visalia’s turn: whites “burned down the whole Chinatown,” according to a man born there in 1900 who remembered that it happened when he was small. In June 1906, the city council of Santa Ana, California, passed a resolution that called for “the fire department to burn each and every one of the said buildings known as Chinatown”; on June 26 a crowd of more than a thousand watched it burn. Many of these towns enacted policies excluding Chinese Americans and remained “Chinese-free” for decades.

12

12

One of the better-studied expulsions was from Eureka, in Humboldt County in northern California. On February 6, 1885, a city councilman was killed by a stray bullet fired by one of two quarreling Chinese men. White workers had already been clamoring, “The Chinese must go.” That night, some 600 whites met to demand that all Chinese leave Humboldt County within 24 hours. Some white citizens defended the Chinese and tried to keep their own domestic servants but were forced to give them up. The next morning, some 480 Chinese and whatever belongings they could carry were aboard two steamships that then sailed for San Francisco. A week later, “a large crowd assembled at Centennial Hall to hear the report of the citizens’ committee,” according to Lynwood Carranco, who wrote a detailed account of the incident. They adopted several resolutions:

1. )That all Chinamen be expelled from the city and that none be allowed to return.

2. )That a committee be appointed to act for one year, whose duty shall be to warn all Chinamen who may attempt to come to this place to live, and to use all reasonable means to prevent their remaining. If the warning is disregarded, to call mass meetings of citizens to whom the case will be referred for proper action.

3. That a notice be issued to all property owners through the daily papers, requesting them not to lease or rent property to Chinese.

13

Copycat expulsions followed from Arcata, Ferndale, and Crescent City (Portfolio 1 shows a broadside advocating “ridding Crescent City of Chinese”). By October 1906, some 23 Chinese workers had returned to work in a cannery in Humboldt County; they lasted less than a month before whites again drove them out. (Portfolio 2 shows this expulsion.) In 1937 the

Humboldt Times

published a souvenir edition on its 85th anniversary that bragged about its Chinese-free status:

Humboldt Times

published a souvenir edition on its 85th anniversary that bragged about its Chinese-free status:

Humboldt County has the unique distinction of being the only community in which there are no Oriental colonies....

14

Although 52 years have passed since the Chinese were driven from the county, none have ever returned. On one or two occasions offshore vessels with Chinese crews have stopped at this port, but the Chinamen as a rule stayed aboard their vessels, choosing not to take a chance on being ordered out. Chinese everywhere have always looked upon this section of the state as “bad medicine” for the Chinamen.

15

The attacks on Chinese in the West grew so bad that Mark Twain famously said, “A Chinaman had no rights that any man was bound to respect,” deliberately echoing Roger Taney’s words in

Dred Scott.

Whites even tried to drive out Chinese from large cities such as San Francisco and Seattle but failed, owing to the enormity of the task.

16

The Chinese Retreat and the Great RetreatDred Scott.

Whites even tried to drive out Chinese from large cities such as San Francisco and Seattle but failed, owing to the enormity of the task.

16

From 1890 to the 1930s, whites across the North (and the nontraditional South) began to do to African Americans what westerners had done to Chinese Americans.

17

The Chinese retreat can be dated from the mid-1870s to about 1910, antedating the Great Retreat by fifteen to twenty years. There were other differences. Because Chinese Americans were not citizens, and because they had played no role in the Civil War, it was much harder for anti-racists to mobilize sentiment on their behalf. In 1879, only 900 California voters supported continued Chinese immigration, while 150,000 favored keeping them out. Also, municipal policies to keep out Chinese Americans mostly relaxed in the 1970s or even earlier, while sundown towns vis-à-vis African Americans lasted much longer.

17

The Chinese retreat can be dated from the mid-1870s to about 1910, antedating the Great Retreat by fifteen to twenty years. There were other differences. Because Chinese Americans were not citizens, and because they had played no role in the Civil War, it was much harder for anti-racists to mobilize sentiment on their behalf. In 1879, only 900 California voters supported continued Chinese immigration, while 150,000 favored keeping them out. Also, municipal policies to keep out Chinese Americans mostly relaxed in the 1970s or even earlier, while sundown towns vis-à-vis African Americans lasted much longer.

However, there are at least seven close parallels between the two movements. First, Democrats led the attacks on both groups, in line with their position as the party of white supremacy. Second, there was some safety in numbers; ironically, some of the largest and most vicious race riots proved that. Although they tried, whites could not drive all Chinese Americans from Seattle, San Francisco, or Los Angeles. They succeeded in smaller places such as Rock Springs and Humboldt County. Similarly, blacks did find some refuge in majority-black neighborhoods in the inner city. Whites usually proved reluctant to venture far into alien territory to terrorize residents. Although whites attacked black neighborhoods in Chicago; East St. Louis, Illinois; Washington, D.C.; Tulsa; and other cities between 1917 and 1924, they were unable to destroy them for good.

Third, whites sometimes allowed one or two members of the despised race to stay, even as they forced out all others, especially if a rich white family protected them. Fourth, both groups often resisted being expelled or violated the bans. The 1906 return by Chinese Americans to Humboldt County offers a case in point; African Americans also returned repeatedly to towns that had driven them out. Fifth, after one town drove out or kept out Chinese Americans, whites in nearby towns often asked, “Why haven’t

we

done that?” so an epidemic of expulsions resulted. Expulsions or prohibitions of African Americans likewise proved contagious, sweeping through whole regions. Sixth, once a community defined itself as a sundown town—vis-à-vis Chinese or African Americans—typically it stayed that way for decades and celebrated its all-white status openly. Eureka did not repeal its anti-Chinese ordinance until 1959. Some sundown towns vis-à-vis African Americans

still

maintain their all-white status, although less openly than in the past.

we

done that?” so an epidemic of expulsions resulted. Expulsions or prohibitions of African Americans likewise proved contagious, sweeping through whole regions. Sixth, once a community defined itself as a sundown town—vis-à-vis Chinese or African Americans—typically it stayed that way for decades and celebrated its all-white status openly. Eureka did not repeal its anti-Chinese ordinance until 1959. Some sundown towns vis-à-vis African Americans

still

maintain their all-white status, although less openly than in the past.

Finally, and most important for our purposes, Chinatowns became the norm for Chinese American life only

after

the Chinese Retreat—about 1884 to 1910. Likewise, only after the Great Retreat did big-city ghettoes become the dwelling places of most northern blacks. African Americans were a

rural

people in the nineteenth century, and not just in the South, from which they moved, but also in the North, to which they came. In 1890 the proportion of black Illinoisans living in Chicago, for example (25%), was less than that for whites (29%). Nevertheless, by 1940 amnesia set in, and Americans forgot completely that in the nineteenth century, Chinese had lived in towns and hamlets throughout the West, while blacks had moved to little towns and rural areas across the North. Americans also repressed the memory of the expulsions and ordinances that created sundown towns. Now Americans typecast African Americans as residents of places such as Harlem and the South Side of Chicago, and Chinese Americans as Chinatown dwellers.

18

after

the Chinese Retreat—about 1884 to 1910. Likewise, only after the Great Retreat did big-city ghettoes become the dwelling places of most northern blacks. African Americans were a

rural

people in the nineteenth century, and not just in the South, from which they moved, but also in the North, to which they came. In 1890 the proportion of black Illinoisans living in Chicago, for example (25%), was less than that for whites (29%). Nevertheless, by 1940 amnesia set in, and Americans forgot completely that in the nineteenth century, Chinese had lived in towns and hamlets throughout the West, while blacks had moved to little towns and rural areas across the North. Americans also repressed the memory of the expulsions and ordinances that created sundown towns. Now Americans typecast African Americans as residents of places such as Harlem and the South Side of Chicago, and Chinese Americans as Chinatown dwellers.

18

In reality, white evictions and prohibitions provided the most important single reason for these retreats to large cities. In places where no such pressures existed, such as Mississippi, Chinese Americans continued to live throughout the Nadir period, sprinkled about in tiny rural towns such as Merigold and Louise; few lived in the metropolitan areas of Jackson or the Gulf Coast.

19

The Great Retreat Was National19

What happened next was national, not regional, and affected America’s largest minority, far more than the 100,000 Chinese Americans then in the country. From town after town, county after county—even from whole regions—African Americans were driven by white opposition, winding up in huge northern ghettoes.

Sometimes this was accomplished by violence, sometimes by subtler means; the next chapter tells how sundown towns were created. Here it is important to understand that we are not talking about a handful of sundown towns sprinkled across America. The Great Retreat left in its wake a new geography of race in the United States. From Myakka City, Florida, to Kennewick, Washington, the nation is dotted with thousands of all-white towns that are (or were until recently) all white on purpose. Sundown towns can be found in almost every state.

20

This chapter takes us on a whirlwind journey around the United States, exploring sundown towns and counties in every region. Independent sundown towns are fairly common in the East, frighteningly so in the Midwest, nontraditional South, and Far West, but rare in the traditional South. Sundown suburbs are common everywhere, although they are now disappearing in the South and Far West. Indeed, because sundown towns proved to be so numerous, this chapter proved the hardest to write. If it described or even merely listed sundown towns by state, the chapter would become impossibly long, but if it only generalized about the extent of the problem, it would be unconvincing. I tried to find a middle path, a mix of examples and generalities, and set up a web site,

uvm.edu/~jloewen/sundown

, giving many more examples.

County Populations Show the Great Retreat20

This chapter takes us on a whirlwind journey around the United States, exploring sundown towns and counties in every region. Independent sundown towns are fairly common in the East, frighteningly so in the Midwest, nontraditional South, and Far West, but rare in the traditional South. Sundown suburbs are common everywhere, although they are now disappearing in the South and Far West. Indeed, because sundown towns proved to be so numerous, this chapter proved the hardest to write. If it described or even merely listed sundown towns by state, the chapter would become impossibly long, but if it only generalized about the extent of the problem, it would be unconvincing. I tried to find a middle path, a mix of examples and generalities, and set up a web site,

uvm.edu/~jloewen/sundown

, giving many more examples.

One way to show the Great Retreat is by examining the population of African Americans by county. Between 1890 and 1930 or 1940, the absolute number of African Americans in many northern counties and towns plummeted.

21

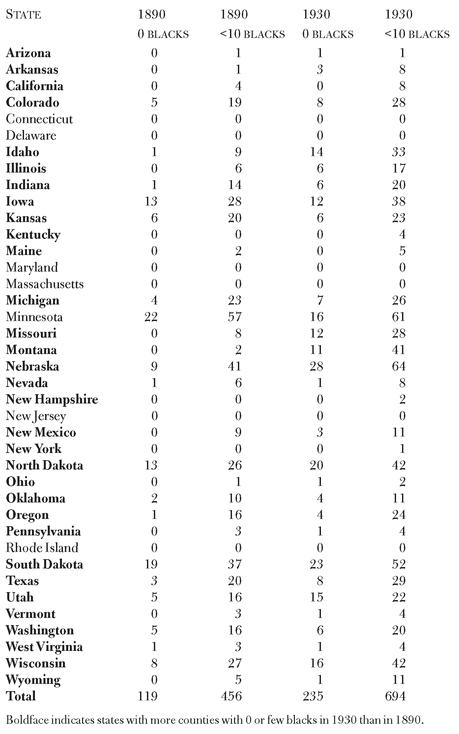

Table 1

, “Counties with No or Few African Americans’ in 1890 and 1930,” shows this phenomenon in several ways. The “total” row at the bottom of the table shows that, as a result of the relatively welcoming atmosphere of the 1860s–80s, only 119 counties in the United States (excluding the traditional South) had no African American residents in 1890.

But by 1930, the number of counties with not a single African American had nearly doubled, to 235.

Counties with just a handful of African Americans (fewer than 10) also increased, from 452 in 1890 to 694 by 1930.

22

Many entire counties that had African Americans in 1890 had none by 1930. Other counties with sizable black populations in 1890 had only a handful of African Americans by 1930.

21

Table 1

, “Counties with No or Few African Americans’ in 1890 and 1930,” shows this phenomenon in several ways. The “total” row at the bottom of the table shows that, as a result of the relatively welcoming atmosphere of the 1860s–80s, only 119 counties in the United States (excluding the traditional South) had no African American residents in 1890.

But by 1930, the number of counties with not a single African American had nearly doubled, to 235.

Counties with just a handful of African Americans (fewer than 10) also increased, from 452 in 1890 to 694 by 1930.

22

Many entire counties that had African Americans in 1890 had none by 1930. Other counties with sizable black populations in 1890 had only a handful of African Americans by 1930.

These findings fly in the face of normal population diffusion, which would predict continued dispersal over time. Thus the number of counties with no members of a group would normally decrease, even if no new members of the group entered the overall system, just from the ordinary haphazard moves of individuals and families from place to place. That the opposite happened is quite surprising and indicates the withdrawal of African Americans from many counties across the Northern states.

Table 1

excludes the traditional South;

23

we shall see why shortly.

Table 1

excludes the traditional South;

23

we shall see why shortly.

Table 1

. Counties with No or Few (< 10) African Americans, 1890 and 1930

. Counties with No or Few (< 10) African Americans, 1890 and 1930

The striking uniformity in

Table 1

also reveals the startling extent of the Great Retreat. Beginning at the top, we note that every Arizona county had at least one African American in 1910, the first year for which data exist. But by 1930, one Arizona county has no African Americans at all. One county is not worth reporting, but the trend grows more pronounced in Arkansas, which also had no county without African Americans in 1890 but had three by 1930, as well as five more with just a handful. The pattern then holds with remarkable consistency in California, Colorado, and all the rest. Of the 39 states in the table,

not one showed greater dispersion of African Americans in 1930 than in 1890. In 31 of 39 states, African Americans lived in a narrower range of counties in 1930 than they did in 1890.

Minnesota showed a mixed result,

24

and seven states—Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island—had virtually no counties in either year with fewer than ten blacks, so they could show no trend in

Table 1

. However, the Appendix provides a closer look at those eight states and reveals that there, too, African Americans concentrated in just a few counties in 1930, to a far greater extent than did whites.

25

Thus those states also fit the pattern; hence every state in

Table 1

shows some confirmation of the Great Retreat.

Table 1

also reveals the startling extent of the Great Retreat. Beginning at the top, we note that every Arizona county had at least one African American in 1910, the first year for which data exist. But by 1930, one Arizona county has no African Americans at all. One county is not worth reporting, but the trend grows more pronounced in Arkansas, which also had no county without African Americans in 1890 but had three by 1930, as well as five more with just a handful. The pattern then holds with remarkable consistency in California, Colorado, and all the rest. Of the 39 states in the table,

not one showed greater dispersion of African Americans in 1930 than in 1890. In 31 of 39 states, African Americans lived in a narrower range of counties in 1930 than they did in 1890.

Minnesota showed a mixed result,

24

and seven states—Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island—had virtually no counties in either year with fewer than ten blacks, so they could show no trend in

Table 1

. However, the Appendix provides a closer look at those eight states and reveals that there, too, African Americans concentrated in just a few counties in 1930, to a far greater extent than did whites.

25

Thus those states also fit the pattern; hence every state in

Table 1

shows some confirmation of the Great Retreat.

Other books

El desierto de hielo by Maite Carranza

Wild Ride: A Bad Boy Romance by Roxeanne Rolling

Enticing Miss Eugenie Villaret by Ella Quinn

Eucalyptus by Murray Bail

The Illumination by Kevin Brockmeier

The Girl he Never Noticed by Lindsay Armstrong

Children Of The Mountain (Book 2): The Devil You Know by Hakok, R.A.

Sea Swept by Nora Roberts

The Darkening by Robin T. Popp

Terminus by Baker, Adam