Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (13 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

8.77Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

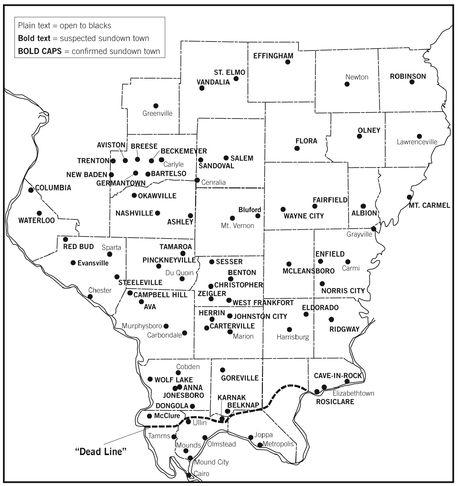

Map 1. Centers of Manufacturing in Southern Illinois

In 1952 Charles Colby mapped 80 communities in southern Illinois—including every larger city, many towns, and some hamlets—all chosen because they had factories. Identifying their racial policies shows how widespread sundown towns were, at least in this subregion. Of his 80 towns, 55 or 69% are suspected sundown towns, “all-white” for decades. Among these 55, I confirmed the racial policies of 52, and of those 52, 51 (all but Newton) were sundown towns.

The dotted line at the bottom is the “dead line,” north of which African Americans were not allowed to live (except in the unbolded towns). South of this line, cotton was the major crop; white landowners employed black labor, following the southern tradition of hierarchical race relations rather than northern sundown policies. All 8 towns below this line allowed African Americans to live in them. Among the 72 towns above the line, only 18—less than a quarter—did so to my knowledge.

Villa Grove, a central Illinois town seventeen miles south of Champaign-Urbana, is newer and smaller than LaSalle-Peru, but equally white. After I spoke in Decatur in October 2001, two people came forward to say they had heard that Villa Grove had or has a whistle or siren that sounded every evening at 6 PM to tell all African Americans to be out of town. I filed the story under “urban legends,” thinking it absurd that anyone could possibly worry that any substantial number of African Americans were clamoring to get

into

Villa Grove, a town of 2,553 people located on no major highway. The story did suggest that Villa Grove is a sundown town, however, so I visited the town. To my surprise, interview after interview confirmed the whistle story. Today Villa Grove is both a local service center supplying the needs of surrounding farmers and a bedroom community for Champaign-Urban. Some Champaign-Urbana residents moved to Villa Grove and now commute to work to minimize their contact with African Americans in Champaign-Urbana. One African American woman at the University of Illinois told of conversations with a white colleague at her former job. He was a native of Villa Grove, as was his wife, from whom he had separated. As he recounted it, his wife insisted that he wash his hands at her home before picking up their daughters for weekend visitation, because she knew an African American was employed at his workplace and they might have touched common objects.

46

into

Villa Grove, a town of 2,553 people located on no major highway. The story did suggest that Villa Grove is a sundown town, however, so I visited the town. To my surprise, interview after interview confirmed the whistle story. Today Villa Grove is both a local service center supplying the needs of surrounding farmers and a bedroom community for Champaign-Urban. Some Champaign-Urbana residents moved to Villa Grove and now commute to work to minimize their contact with African Americans in Champaign-Urbana. One African American woman at the University of Illinois told of conversations with a white colleague at her former job. He was a native of Villa Grove, as was his wife, from whom he had separated. As he recounted it, his wife insisted that he wash his hands at her home before picking up their daughters for weekend visitation, because she knew an African American was employed at his workplace and they might have touched common objects.

46

In July 1899, striking white miners drove a group of African American strikebreakers down the railroad tracks out of Carterville, a town of 3,600 in southern Illinois. In the process, they shot five of them dead. Eventually the whites were all acquitted, the strikers won, and all African Americans were forced to leave. Carterville had already pushed the sundown town concept to a new level before 1899, not permitting African Americans to set foot inside the city limits, even during the day. This policy remained in force for decades. Even Dr. Andrew Springs, the black physician serving Dewmaine, a small black community about a mile north of Carterville, had to wait at the edge of town in the 1930s for drugs he had ordered from Carterville’s pharmacy to be delivered to him. In the late 1970s, the first black family moved in. According to Carl Planinc, who has lived in Carterville for several decades, “ironically, their first night, there was a fire, and their house burned down.”

47

47

Stories such as these exist for each town that I list as confirmed, and I believe similar information, differing only in detail, remains to be harvested from almost every one of Illinois’s 474 all-white towns. What about other states? Roberta Senechal, one of the handful of authors who have mentioned sundown towns, noted that “such banning of blacks by custom and unwritten law from rural and small-town communities was not a phenomenon limited to Illinois.” She is right, of course, so I widened my circle, turning first to Indiana, next door.

48

48

Indiana showed a similar pattern. Of course, of all states, Indiana is most like Illinois and borders it for 300 miles. In 1964, in an affectionate memoir,

My Indiana,

Irving Leibowitz wrote, “Intolerance was everywhere. ‘NIGGER, DON’T LET THE SUN SET ON YOU HERE,’ was a sign posted in most every small town in Indiana.” As in Illinois, whole Indiana counties kept out African Americans entirely or restricted them to one or two small hamlets.

49

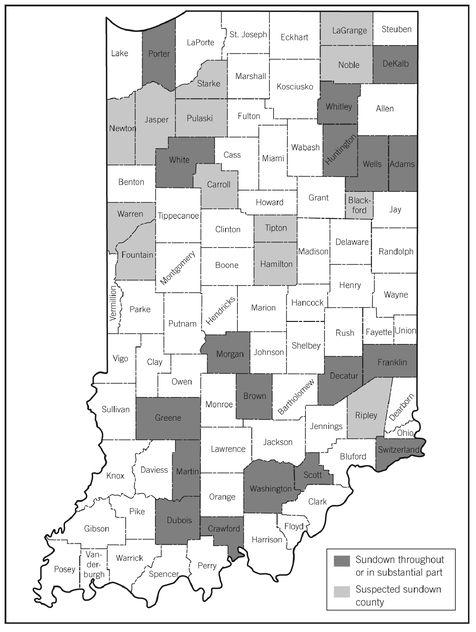

Map 2 shows eighteen confirmed sundown counties and fifteen suspects in 1970. In addition, many confirmed sundown towns lie sprinkled across Indiana’s unshaded counties.

50

My Indiana,

Irving Leibowitz wrote, “Intolerance was everywhere. ‘NIGGER, DON’T LET THE SUN SET ON YOU HERE,’ was a sign posted in most every small town in Indiana.” As in Illinois, whole Indiana counties kept out African Americans entirely or restricted them to one or two small hamlets.

49

Map 2 shows eighteen confirmed sundown counties and fifteen suspects in 1970. In addition, many confirmed sundown towns lie sprinkled across Indiana’s unshaded counties.

50

Some Indiana sundown towns were famous for their policy. Elwood’s moment of notoriety as a sundown town came in 1940 when native son Wendell Willkie was nominated for president there. Its population was then 11,000; as many as 150,000 people crowded in for the rally. Frances Peacock wrote a memoir about two black Republicans who never made it, George Sawyer and his father:

In 1940 George and his father, an active Republican, were on their way to Elwood, Indiana, to attend a rally for Wendell Willkie, the Republican presidential candidate. When they arrived at Elwood that morning before the convention, they saw two road signs posted at the city limits: “Niggers, read this and run. If you can’t read, run anyhow,” and “Nigger, don’t let the sun set on you in Elwood.”George’s father turned the car around and drove back to Anderson. And from then on, he was a Democrat.

51

Map 2. Sundown Counties in Indiana

Indiana had only 1 black-free county in 1890, but 6 by 1930, as well as 27 others with a handful of African Americans. All 33 were probably sundown counties; I have confirmed 18.

I identified a total of 231 Indiana towns as all-white.

52

I was able to get information as to the racial policies of 95, and of those, I confirmed all 95 as sundown towns.

53

In Indiana, I have yet to uncover

any

overwhelmingly white town that on-site research failed to confirm as a sundown town. Ninety-five out of 95 is an astounding proportion; statistical analysis shows that it is quite likely that 90 to 100% of all 231 were sundown towns. They ranged from tiny hamlets to cities in the 10,000–50,000 population range, including Huntington (former vice president Dan Quayle’s hometown) and Valparaiso (home of Valparaiso University).

52

I was able to get information as to the racial policies of 95, and of those, I confirmed all 95 as sundown towns.

53

In Indiana, I have yet to uncover

any

overwhelmingly white town that on-site research failed to confirm as a sundown town. Ninety-five out of 95 is an astounding proportion; statistical analysis shows that it is quite likely that 90 to 100% of all 231 were sundown towns. They ranged from tiny hamlets to cities in the 10,000–50,000 population range, including Huntington (former vice president Dan Quayle’s hometown) and Valparaiso (home of Valparaiso University).

Portfolio 25 shows the last page from the 1970 census for Indiana towns with 1,000 to 2,499 residents.

54

Note the striking number of dashes in the “Negro” column—towns that had not a single African American. Surely Leibowitz was right. Indeed, almost four decades after Leibowitz wrote, my research uncovered oral or written history, usually from more than one source, of actual sundown signs posted in at least 21 Indiana communities.

55

Most had come down by the end of World War II, but according to Mike Haas, signs in the little town of Sunman said “NIGGER! BETTER NOT BE SEEN HERE AFTER SUNDOWN!” until well into the 1980s. The most recent sign was spotted in White County in 1998.

56

54

Note the striking number of dashes in the “Negro” column—towns that had not a single African American. Surely Leibowitz was right. Indeed, almost four decades after Leibowitz wrote, my research uncovered oral or written history, usually from more than one source, of actual sundown signs posted in at least 21 Indiana communities.

55

Most had come down by the end of World War II, but according to Mike Haas, signs in the little town of Sunman said “NIGGER! BETTER NOT BE SEEN HERE AFTER SUNDOWN!” until well into the 1980s. The most recent sign was spotted in White County in 1998.

56

Intentionally all-white communities dot the rest of the Midwest. In Ohio, independent sundown towns are found from Niles in the north to Syracuse on the Ohio River, and sundown suburbs proliferate around Cincinnati and Cleveland. Missouri has an extraordinary number of sundown towns, at least 200. Many are in the Ozarks and will be treated later in this chapter, but the more midwestern parts of Missouri have dozens of sundown towns and counties as well. In sum, by 1930 probably a majority of all towns in the heartland kept out African Americans. No wonder blacks moved to Chicago and St. Louis.

Sundown Towns in the Far NorthClearly sundown towns were a phenomenon throughout the lower Midwest. But what about states farther north? Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois border former slave states, after all, and Missouri was a slave state, so they were near black populations. Initially I did not expect to find sundown towns in far northern states such as Maine, Michigan, Wisconsin, Idaho, or Oregon. I labored under the misapprehension that all-white towns so far north were unlikely to be purposeful. I thought that because these states were so distant from African American population centers, it may be unreasonable to expect their towns to have black residents in the first place. Also I imagined that whites so far north, faced with no possible “threat” from any large number of African Americans, would be unlikely to adopt exclusionary policies. I was wrong on both counts.

Take Wisconsin, for example, not usually considered a place where African Americans concentrated, except perhaps Milwaukee. In 1890, the state was indeed only 0.15% black. Nevertheless, before 1890, black people hardly limited themselves to Milwaukee.

Table 1

shows that only 8 of Wisconsin’s 68 counties held no African Americans in 1890; another 27 counties had fewer than 10. Twenty-six counties had at least twenty African Americans, and these were sprinkled about the state. Four counties around Lake Winnebago—Calumet, Fond du Lac, Outagamie, and Winnebago—boasted 389 African Americans among them, almost as many as Milwaukee. In all, 1,986 African Americans lived outside of Milwaukee, along with 458 black Milwaukeeans.

Table 1

shows that only 8 of Wisconsin’s 68 counties held no African Americans in 1890; another 27 counties had fewer than 10. Twenty-six counties had at least twenty African Americans, and these were sprinkled about the state. Four counties around Lake Winnebago—Calumet, Fond du Lac, Outagamie, and Winnebago—boasted 389 African Americans among them, almost as many as Milwaukee. In all, 1,986 African Americans lived outside of Milwaukee, along with 458 black Milwaukeeans.

By 1930, the number of African Americans living in Milwaukee had swelled almost tenfold to 4,188, while outside Milwaukee lived fewer blacks—just 1,623—than in 1890. In 1890, less than 20% of Wisconsin’s African Americans lived in Milwaukee; by 1930, 72% did. The most dramatic declines came in the counties around Lake Winnebago, by 1930 home to just 86 African Americans, most of them in Winnebago County. Fond du Lac’s 178 African Americans in 1880 dwindled to just 22 in 1930 and 5 by 1940. Statewide, 16 counties had no African Americans at all by 1930, and another 42 had fewer than ten.

Among its 144 cities of more than 2,500 population in 1970, Wisconsin had 126 all-white communities (as defined in Chapter 1). No prior published histories treat the phenomenon of sundown towns in Wisconsin, so far as I know, and I could not spend nearly as much time doing oral history in Wisconsin as in Illinois and Indiana. Nevertheless, I confirmed nine as sundown towns; for ten others, including several towns near Lake Winnebago, I have some evidence.

57

I am sure that many additional Wisconsin towns, including several Milwaukee suburbs, also excluded African Americans, but have not done on-site research to prove it.

57

I am sure that many additional Wisconsin towns, including several Milwaukee suburbs, also excluded African Americans, but have not done on-site research to prove it.

Some Wisconsin sundown towns were tiny hamlets; even some unincorporated rural locales kept out African Americans by refusing to sell them land or hire them as farm labor. Some were startingly large cities, such as Appleton, population 60,000, and Sheboygan, 45,000.

58

Sheboygan, for example, acted as if it had passed a sundown ordinance: it had a police officer meet trains at the railroad station to warn African Americans not to stay there, according to a resident there in the early 1960s. At least one town, Manitowoc, posted signs. Grey Gundaker, now a professor at the College of William and Mary, saw them when he lived there from 1962 to 1964: “The signs were worded approximately ‘NIGGER: Don’t let the sun go down on you in our town!’ ” he recalls. “I think the words were in italics and painted across a picture of a green hill with the sun setting halfway behind it.”

59

58

Sheboygan, for example, acted as if it had passed a sundown ordinance: it had a police officer meet trains at the railroad station to warn African Americans not to stay there, according to a resident there in the early 1960s. At least one town, Manitowoc, posted signs. Grey Gundaker, now a professor at the College of William and Mary, saw them when he lived there from 1962 to 1964: “The signs were worded approximately ‘NIGGER: Don’t let the sun go down on you in our town!’ ” he recalls. “I think the words were in italics and painted across a picture of a green hill with the sun setting halfway behind it.”

59

Beaver Dam, 60 miles northwest of Milwaukee, grew steadily from 4,222 people in 1890 to 10,356 in 1940 and 14,265 in 1970. Despite this growth, its black population fell from eight in 1890 to just one a decade later, then stayed at one or two until after 1970.

60

A 1969 report at Wayland Academy, a prep school located in Beaver Dam, evaluated “the feasibility of admitting Negroes to Wayland”; its authors interviewed townspeople “to determine problems which might face a Negro as he lives in this presently nonintegrated community.” Several older inhabitants of Beaver Dam “all said the same thing in the same words” to Moira Meltzer-Cohen, Beaver Dam resident and resourceful researcher: “ ‘A couple of black families tried to move in during the’60s and ’70s and they were run right out.’ ”

61

60

A 1969 report at Wayland Academy, a prep school located in Beaver Dam, evaluated “the feasibility of admitting Negroes to Wayland”; its authors interviewed townspeople “to determine problems which might face a Negro as he lives in this presently nonintegrated community.” Several older inhabitants of Beaver Dam “all said the same thing in the same words” to Moira Meltzer-Cohen, Beaver Dam resident and resourceful researcher: “ ‘A couple of black families tried to move in during the’60s and ’70s and they were run right out.’ ”

61

Other books

Psychobyte by Cat Connor

Hunger of the Heart (Wolves of Ravenwillow Book 1) by Magenta Phoenix

The Burglary by Betty Medsger

Dinesh D'Souza - America: Imagine a World without Her by Dinesh D'Souza

Bound In Blood (The Adams' Witch Series Book 1) by Butler, Erin

Nivel 5 by Lincoln Child Douglas Preston

A Hero's Heart by Sylvia McDaniel

Eve Silver by Dark Desires

Heaven in a Wildflower by Patricia Hagan

Cleopatra by Kristiana Gregory