Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (14 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

7.68Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Wisconsin exemplifies findings from other far north states. Oregon had just one county with no African Americans at all in 1890, although it had sixteen more with fewer than ten. By 1930, however, Oregon had four counties with no African Americans and twenty more with fewer than ten. Exclusion was responsible. Correspondents have sent me evidence confirming that a string of towns along what is now Interstate 5 in western Oregon, for instance, including Eugene, Umpqua, Grants Pass, Eagle Point, Medford, and others, kept out African Americans until the recent past. Other examples across the far north from west to east include Kennewick and Richland in Washington; Ashton and Wallace in Idaho, and probably all of Lemhi County; Austin, Minnesota; many towns in Michigan; and Tonawanda and North Tonawanda in New York, almost on the Canadian border. Wallace, for example, expelled its Chinese in the nineteenth century; in the twentieth it put up a sign at the edge of town that said “Nigger, Read This Sign and Run”; and in the 2000 census it still had no African Americans and just one Asian American. So even in the Idaho panhandle up by Canada, towns felt the need to keep out people of color.

62

The Great Retreat Did Not Strike the “Traditional South”62

Very different race relations evolved in what I call the “traditional South”—Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana, all states historically dominated by slavery.

63

There, in contrast to the North, slavery grew more entrenched after the American Revolution. Some whites grew wealthy from the unpaid labor, and most others yearned to emulate them. After slavery ended, the tradition continued in the form of sharecropping, which kept many blacks in peonage, unable to pay the perpetual debt by which white landowners bound them to the land. In towns, blacks continued to do the domestic chores, janitoring, and backbreaking work that whites avoided—now in exchange for inadequate wages. To hire blacks, whom they could pay less than whites, was in the interest of plantation owners, railroads, and other employers.

63

There, in contrast to the North, slavery grew more entrenched after the American Revolution. Some whites grew wealthy from the unpaid labor, and most others yearned to emulate them. After slavery ended, the tradition continued in the form of sharecropping, which kept many blacks in peonage, unable to pay the perpetual debt by which white landowners bound them to the land. In towns, blacks continued to do the domestic chores, janitoring, and backbreaking work that whites avoided—now in exchange for inadequate wages. To hire blacks, whom they could pay less than whites, was in the interest of plantation owners, railroads, and other employers.

County populations in the traditional South do not show the Great Retreat. Indeed, during the Nadir, when sundown towns were most in vogue, whites from the traditional South expressed astonishment at the practice. Why expel your maid, your agricultural workforce, your school janitor, your railroad track layers? Writing about Washington County, Indiana, Emma Lou Thornbrough noted that African Americans “were not allowed to come in even as servants, a fact which occasioned surprise among visitors from the South.” Traditional white southerners saw African Americans as workers to be exploited and sometimes as problems to be controlled but not expelled.

64

64

Therefore the traditional South has almost no independent sundown towns, and never did. This does not make whites in the traditional South less racist than in other parts of the South or other regions of the country. Racist they were—indeed, racism arose in Western cultures primarily as a rationale for racial slavery—but the tradition entailed controlling and exploiting blacks, not getting rid of them. Indeed, the original sundown rule was a curfew at dusk during slavery times; to be out after dark, slaves had to have written passes from their owners. After slavery ended in the traditional South, whites often lynched African Americans to keep them down; elsewhere in the United States, whites sometimes lynched them, we will see, to drive them out.

Thus Mississippi, for example, has just two all-white towns with a population over 1,000, Belmont and Burnsville, and they lie barely in the state, in the northeast corner near the Alabama line, in Appalachia.

65

It also had three suburbs that excluded African Americans between 1945 and 1975. Alabama has two sundown counties and a handful of sundown towns, but all except one are in far north Alabama—in Appalachia, not in the traditional South—and the exception is a sundown suburb of Mobile.

66

Louisiana has a few, but they are tiny. The cotton culture part of Arkansas boasts not a single sundown town. California has more sundown towns than all parts of the traditional South put together. Illinois has many times more.

The Great Retreat from the Rest of the South65

It also had three suburbs that excluded African Americans between 1945 and 1975. Alabama has two sundown counties and a handful of sundown towns, but all except one are in far north Alabama—in Appalachia, not in the traditional South—and the exception is a sundown suburb of Mobile.

66

Louisiana has a few, but they are tiny. The cotton culture part of Arkansas boasts not a single sundown town. California has more sundown towns than all parts of the traditional South put together. Illinois has many times more.

More like the Midwest and West is the “nontraditional South”—Appalachia, the Cumberlands, the Ozarks, much of Florida, and north and west Texas. There, huge swaths of counties, as well as many individual towns, drove out their African Americans beginning in about 1890.

67

Follansbee, West Virginia, for example, kept out African Americans “for years” before the early 1920s. Then some mills brought in African Americans as employees. In October 1923, the Ku Klux Klan burned two fiery crosses and painted a threat on the fence facing “the colored section,” warning all blacks to leave immediately, according to the

Pittsburgh Courier.

They fled, and the sundown policy apparently remained in force, for in 2000, Follansbee had 3,115 people, but not a single African American household.

68

67

Follansbee, West Virginia, for example, kept out African Americans “for years” before the early 1920s. Then some mills brought in African Americans as employees. In October 1923, the Ku Klux Klan burned two fiery crosses and painted a threat on the fence facing “the colored section,” warning all blacks to leave immediately, according to the

Pittsburgh Courier.

They fled, and the sundown policy apparently remained in force, for in 2000, Follansbee had 3,115 people, but not a single African American household.

68

Table 1

shows that much of the nontraditional South did expel its African Americans during the Nadir. Arkansas shows the difference dramatically. In 1890, it had no county without African Americans and only one with fewer than ten; by 1930, three counties had none and another eight had fewer than ten, all in the Arkansas Ozarks. I suspect all eleven were sundown counties and have confirmed six. If we draw a line from the southwest corner of Arkansas northeast to the Missouri Bootheel, the resulting triangle bordering Oklahoma and Missouri includes all 11 counties and all 74 suspected sundown towns in Arkansas. The southeastern part of the state, in contrast, where cotton culture dominated and secession sentiment was strongest, includes not a single sundown town or county.

shows that much of the nontraditional South did expel its African Americans during the Nadir. Arkansas shows the difference dramatically. In 1890, it had no county without African Americans and only one with fewer than ten; by 1930, three counties had none and another eight had fewer than ten, all in the Arkansas Ozarks. I suspect all eleven were sundown counties and have confirmed six. If we draw a line from the southwest corner of Arkansas northeast to the Missouri Bootheel, the resulting triangle bordering Oklahoma and Missouri includes all 11 counties and all 74 suspected sundown towns in Arkansas. The southeastern part of the state, in contrast, where cotton culture dominated and secession sentiment was strongest, includes not a single sundown town or county.

Similarly, most sundown towns and counties in Texas are in north Texas or southwest of Fort Worth, rather than in the traditionally southern areas of East Texas. Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri also show this pattern: their sundown towns are in the hills and mountains or are suburbs. Maryland’s one sundown county, Garrett, is its farthest west, in Appalachia. Garrett County doesn’t show in

Table 1

but had become overwhelmingly white by 1940. At least two far west counties in Virginia and two in North Carolina, along with two counties and several towns in east Tennessee, also went sundown after 1890. So did six counties in north Georgia—including Forsyth—and most of Winston County in northern Alabama. Indeed, the Great Retreat was particularly pronounced from the nontraditional South. Map 3 shows some of the areas in the nontraditional South where many counties and towns went sundown, almost all after about 1890.

Table 1

but had become overwhelmingly white by 1940. At least two far west counties in Virginia and two in North Carolina, along with two counties and several towns in east Tennessee, also went sundown after 1890. So did six counties in north Georgia—including Forsyth—and most of Winston County in northern Alabama. Indeed, the Great Retreat was particularly pronounced from the nontraditional South. Map 3 shows some of the areas in the nontraditional South where many counties and towns went sundown, almost all after about 1890.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, whites expelled African Americans from almost the entire Cumberland Plateau, a huge area extending from the Ohio River near Huntington, West Virginia, southwest through Corbin, Kentucky, crossing into Tennessee, where it marks the division between east and middle Tennessee, and finally ending in northern Alabama. In most parts of the plateau throughout most of the twentieth century, when night came to the Cumberlands, African Americans had better be absent.

69

The twenty Cumberland counties in eastern Kentucky had 3,482 African Americans in 1890, or 2% of the region’s 175,631 people. By 1930, although their overall population had increased by more than 50%, these counties had only 1,387 black residents. The decline continued: by 1960 the African American population of these counties had declined to just 531, or 0.2%, one-tenth the 1890 proportion.

69

The twenty Cumberland counties in eastern Kentucky had 3,482 African Americans in 1890, or 2% of the region’s 175,631 people. By 1930, although their overall population had increased by more than 50%, these counties had only 1,387 black residents. The decline continued: by 1960 the African American population of these counties had declined to just 531, or 0.2%, one-tenth the 1890 proportion.

Throughout the plateau, this decline was forced. Picking a few examples from north to south, Rockcastle County, Kentucky, had a sundown sign up as late as the mid-1990s, according to George Brosi, editor of

Appalachian Heritage.

In the 1990 census, Rockcastle had no African Americans among its 14,743 people. Esther Sanderson, historian of Scott County, Tennessee, made clear her county’s policy:

Appalachian Heritage.

In the 1990 census, Rockcastle had no African Americans among its 14,743 people. Esther Sanderson, historian of Scott County, Tennessee, made clear her county’s policy:

There was a big sign on the road at the Kentucky state line and at the entrance at Morgan County [the next county south]: “Nigger, don’t let the sun set on your head.” The Negroes rarely ever passed through; if they did, they made haste to get through.

Farther south, the sundown policy of Grundy County, Tennessee, garnered national attention in the 1950s when Myles Horton defied it and located his Highlander Folk School, famed for training civil rights leaders, there.

70

Highlander’s interracial policy was unpalatable to the county, so in 1959 they got the Tennessee legislature to investigate the school. Eventually Grundy County took Highlander to court and forced the institution to leave, charging Horton with beer sales on its property. Did race have anything to do with it? Paul Cook, Grundy County resident and a member of the jury that found Highlander guilty, assures us it did not:

70

Highlander’s interracial policy was unpalatable to the county, so in 1959 they got the Tennessee legislature to investigate the school. Eventually Grundy County took Highlander to court and forced the institution to leave, charging Horton with beer sales on its property. Did race have anything to do with it? Paul Cook, Grundy County resident and a member of the jury that found Highlander guilty, assures us it did not:

That integration business, that didn’t have anything to do with it. Lots of folks around here resent the colored, and we still don’t have any in this county—but they’d have been in trouble without the niggers.

The Cumberland band of sundown towns and counties then continues across the Alabama line into the Sand Mountains, notorious in the 1930s and ’40s for their sundown signs. Portfolio 15 shows a representation of such a sign from the 1930s. Historian Charles Martin told of an “old-timer,” interviewed by one of his students, who used the usual sundown “problem” rhetoric: “We didn’t have any racial problems back then. As long as they were off the mountain by sundown, there weren’t any problems.”

71

71

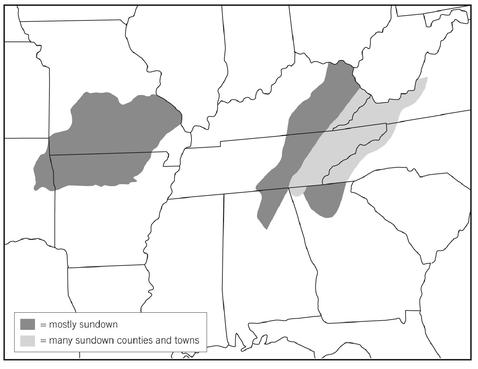

Map 3. Sundown Areas in the Nontraditional South

The lightly-shaded area denotes parts of Appalachia where some counties and towns went sundown, mostly after 1890. Heavily-shaded areas include a V-shaped region in north Georgia, the Cumberlands, and the Ozarks, where

most

counties and towns went sundown, again mainly after 1890.

most

counties and towns went sundown, again mainly after 1890.

The Ozarks also went sundown after 1890. No county in Missouri had zero African Americans in 1890, but by 1930, most of the Ozarks were lily white. The same thing happened across the state line in Arkansas. In 1923, William Pickens saw sundown signs across the Ozarks. And in 2001, Milton Rafferty noted that the black population of the Ozarks declined from 62,000 in 1860 to 31,000 by 1930. The sundown policy of the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks spilled over into northeastern Oklahoma, leaving most of two counties all-white there.

72

72

Noting sundown signs still extant in the 1970s, sociologist Gordon Morgan said African Americans in the Ozarks had coined a new term for the towns they marked: “gray towns.” So far as I know, this term was not used outside the Ozarks. Morgan goes on:

In the not too distant past some vigilante whites thought their duty was to police the towns and, with the tacit support of the law, proceeded to harass any black people who might pass through. Some cars carrying blacks have been stoned, and weapons have been brandished by whites. Even today some blacks will not stop in these gray towns for gas or food even though discrimination in the public places is forbidden.

In 2002, some African Americans who live near the Ozarks said they still avoid the region.

73

The Great Retreat in the West73

Table 1

points to the Great Retreat from every state in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. African Americans left most rural areas and retreated to a handful of cities with black population concentrations. Every state in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains also saw a decline in overall black population percentages. States that had no centers of black population for African Americans to retreat to even saw declines in their absolute numbers of African Americans. The black population of North Dakota, for example, slid from 372 in 1890 to 243 in 1930. As a proportion of the population, blacks dropped from 0.2% in 1890 to a minuscule 0.03% by 1930. In South Dakota the decline was from 0.16% to 0.09%, in Montana from 1.13% to 0.23%. Six counties in Nebraska that had 20 to 50 African Americans each in 1890 had just 1 to 8 by 1930; at the same time, Omaha and Lincoln doubled in black population. Wyoming, the “equality state,” had the largest proportion of African Americans in any of these states—1.52% in 1890, its year of statehood—but by 1930, blacks were only 0.55% of its population. Utah’s blacks likewise decreased as a proportion of the population, and those who remained beat a retreat to Salt Lake and Weber (Ogden) Counties; by 1930, 88% of the state’s African Americans lived in those two counties.

points to the Great Retreat from every state in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. African Americans left most rural areas and retreated to a handful of cities with black population concentrations. Every state in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains also saw a decline in overall black population percentages. States that had no centers of black population for African Americans to retreat to even saw declines in their absolute numbers of African Americans. The black population of North Dakota, for example, slid from 372 in 1890 to 243 in 1930. As a proportion of the population, blacks dropped from 0.2% in 1890 to a minuscule 0.03% by 1930. In South Dakota the decline was from 0.16% to 0.09%, in Montana from 1.13% to 0.23%. Six counties in Nebraska that had 20 to 50 African Americans each in 1890 had just 1 to 8 by 1930; at the same time, Omaha and Lincoln doubled in black population. Wyoming, the “equality state,” had the largest proportion of African Americans in any of these states—1.52% in 1890, its year of statehood—but by 1930, blacks were only 0.55% of its population. Utah’s blacks likewise decreased as a proportion of the population, and those who remained beat a retreat to Salt Lake and Weber (Ogden) Counties; by 1930, 88% of the state’s African Americans lived in those two counties.

Other books

The Enticement: The Submissive Series by Tara Sue Me

Bittersweet by Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

A short history of nearly everything by Bill Bryson

Memoirs of a Bitch by Francesca Petrizzo, Silvester Mazzarella

The Cost of Vengeance by Roy Glenn

La hora de las sombras by Johan Theorin

Dawn (The Dire Wolves Chronicles Book 3) by Alyssa Rose Ivy

Catharsis, Legend of the Lemurians by Lada Ray

Turtle Diary by Russell Hoban

The Robot King by H. Badger