The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (39 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Augustus, on his deathbed, had asked his friends if they had enjoyed watching all the parts he had played so well. He asked them to applaud as he departed the comedy of life, and then had his jaw set and hair combed for his exit. Nero died a grandiloquent death, a tragic actor upon the stage that Augustus had built and that the Julio-Claudians had transformed into high opera.

- The outrageous personal details of the Julio-Claudians come from mostly hostile sources.

- During the reign of the Julio-Claudians, the Roman Empire became more economically, politically, and culturally cohesive.

- As it became clear that the

princeps

held the power, the senate became less involved, and the

princeps

became an emperor. - Those close to the emperor (family, lovers, freedmen, and guards) became extremely powerful and influential.

Â

The (Mostly) Good Emperors: The Flavians to Marcus Aurelius

In This Chapter

- The Roman Empire after the Julio-Claudians

- The chaos after Nero

- The Flavian dynasty and stability

- The so-called good emperors

The rebellions that led to the death of Nero were an ominous blast from the past. Provincial legions proclaimed their own commanders emperor, and factions of the Praetorian Guard complicated the dangerous situation in Rome. For a year, the Roman Empire wobbled like a top as commanders from both west and east moved on Italy to claim power. In the end, however, the chaos of a year led back to a stable and a hereditary dynasty: the “Flavians,” from the family name (Flavius) of its founder, Vespasian. Vespasian was rightly recognized as a second Augustus. This dynasty, however, marked the end of the old Roman nobility's hold over the principate, the increasing importance of provincial armies and citizens in Roman affairs, and the growing cohesion of Rome as a world state.

After Verginius Rufus crushed the rebellion of Vindex, one of the governors of Gaul, in 68 (see Chapter 14, “All in the Family: The Julio-Claudian Emperors”), and refused to be named

princeps

by his own forces, there was a revolving door into the office of the

princeps.

This year is sometimes known as “the year of four emperors.”

Servius Sulpicius Galba, the aging (he was in his 70s) governor of Spain, next maneuvered to power. Galba belonged to an ancient and distinguished Republican family, but his hold on the principate was brief because he failed to make good his financial promises to the praetorians and to the military. There was a good reason for thisâRome was brokeâbut it wasn't a good enough reason for Galba to stay emperor.

Â

Veto!

Remember when you read “year” that, although it always refers to 12 months, the year began at different times for different cultures. This often leads, in chronology, to dates being doubled (for example, the year 68/69). This accounts for events that span one year for a culture but two of our own, or dates that are impossible to pinpoint to one or the other of our years.

Galba alienated the legions by replacing the commander Verginius Rufus, and he alienated his most important supporter, the governor of Lusitania, Marcus Otho, by appointing Otho's rival, Piso, as colleague. Otho took matters into his own hands and secretly bribed the Praetorian Guards to proclaim him emperor. His supporters murdered Piso and Galba and paraded their heads around the palace.

Otho was one of Nero's intimates (perhaps quite intimate), and the former husband of Nero's mistress and then wife, Poppaea. He had a reputation for decadence and dissolution. This reputation, his ties and falling out with Nero, and his violent coup against Galba made nearly every faction deeply suspicious of him. He surprised most, however, by being moderate and trying to work with both Nero's supporters and enemies.

This didn't keep trouble from brewing. The legions of the Rhine and Gaul had declared their commander, Aulus Vitellius, to be the Empire's rightful emperor. Full-scale civil war appeared imminent, but when Vitellius's forces defeated Otho's in battle, Otho advised his supporters to look after themselves as best they could, and committed suicide. This may seem like a coward's way out, but contemporary Romans saw his suicide as a heroic act to spare Rome civil war. He had come a long way in just three months.

If our sources are to be believed, you can't say enough bad about Vitellius. He was a flatterer of Caligula and Claudius, a crony of Nero and Galba. His German legions declared for him in an attempt to secure their commander the place of power (and payment) at the head of Rome. The legions of Gaul and Britain soon followed.

Despite his position, Vitellius had no real military experienceâhe didn't even command the troops that invaded Italy and defeated Otho. He did, however, come to observe the battlefield and made the chilling remark that the smell of dead enemy was sweet and the smell of dead citizen sweeter. He entered Rome a short time later and set up his own troops as the Praetorian Guards and urban cohorts.

Vitellius is known mostly for his ability to eat Rome out of house and home. He spent 900 million

sesterces

on dining alone! (At one banquet, 2,000 fish and 7,000 birds were reportedly consumed.) But Vitellius's principate was running afoul (so to speak) in another way: The legions of the east had declared for Titius Flavius Vespasianus, a general with definite military credentials. Vespasian had been sent by Nero to quell a revolt in Judaea. Now he was holding Egypt while his commander, Mucianus, moved on Italy. Soon the legions of Illyrium and Pannonia joined in and these forces met and butchered Vitellius's forces at Cremona, in almost the same spot that Vitellius had defeated Otho's.

Â

When in Rome

The

sesterce

was a primary coin of the realm. It was worth 2

1

â

2

of the main small coins,

asses

(no relation to the animal), and four sesterces made up a

denarius

, the principal large coin. A Roman soldier made about 900 sesterces a year, so Vitellius's banquets could have funded the legions for about a millennium!

Vitellius tried to abdicate and save his skin, but his supporters declined to accept his resignation. When word of this attempt got out, Vespasian's brother, Sabinus, and friends tried to seize power. Vitellius got the upper hand and had them killed. Two days later, Vespasian's forces fought their way into Rome. Vitellius tried to escape disguised as a commoner (a commoner with a big money belt hidden under his clothes), but he was discovered, tortured to death, and thrown into the Tibur river.

Flavian forces were now in control of Rome. The commander of Syria, Mucianus, administered things until Vespasian arrived. Vespasian's younger son, Domitian, was also in Rome. He came out of hiding and began to act out a version of “I just can't wait to be king.”

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Domitian's premature affectations of power should have been a warning bell. Vespasian, who had a dry sense of humor, got wind of his son's pretensions and wrote him as he traveled to Rome. He thanked his young son for allowing his father to hold office and for not yet dethroning him.

Vespasian not only provided the Empire with a capable emperor, but established the second hereditary imperial dynasty, the Flavians. He was succeeded by his son Titus, and then by his younger son Domitian.

The Flavians brought about a renaissance of Roman stability and prosperity that was compared to Augustus's creation of peace out of the anarchy of the end of the Republic. The Flavian dynasty began with an emperor whose roots, perspective, and work ethic grew out of the equestrian middle class, and concluded at an ultimate end of the ambition for independence and power: the demand to be recognized as lord and god.

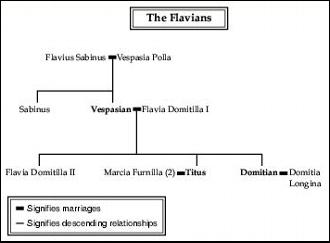

The Flavian dynasty.

Vespasian's parents were middle class Italians (his father was an auctioneer). He had served all over the Empire and gained both experience and accolades under emperors from Tiberius to Claudius. His brother, Sabinus, and he were the first of his family to enter the senate. Vespasian was promoted under Nero to a “companion” and traveled with Nero to Greece, but fell out of favor when he drifted to sleep during one of the emperor's performances. Nevertheless, he was put in charge of quelling a Jewish revolt in Palestine, and was in the process of putting it down and besieging Jerusalem when Nero committed suicide and Rome began to spin into anarchy.

Vespasian stayed in Alexandria holding on to the imperial province of Egypt; he hoped to both conclude putting down the rebellion in Palestine and fulfill his legions' proclamation of him as emperor. He had to leave for Rome before the first was completed, however, and left his son, Titus, in charge. Once in Rome, Vespasian

proved to be an able, determined, practical, and down-to-earth emperor. His background, practical approach, and what one might call “common” humor put off some of the high society, but overall, Vespasian was both respected and successful.

Vespasian and his colleagues such as Mucianus had a reputation for a love of money, and Vespasian maintained a decidedly business-like attitude toward finances as an emperor. Accused by Titus of stinky financial associations, he picked up a coin and remarked, “This, my boy, does not stink.” Despite some rather questionable practices, Vespasian managed the Empire out of destitution into sound fiscal shape. He spent a great deal on public works projects aimed at restoring Rome after Nero's fire and the pillage of the last year. His most famous project was the Colosseum, which he built on the site of the artificial lake of Nero's Golden House.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Vespasian enjoyed witty observations and snappy comebacks, and according to Suetonius, the more lowbrow the better. Nevertheless, he is best known for another of the famous imperial exit lines, and one that displays his practical and sometimes tongue-in-cheek approach to the principate. “Dear me,” he commented on his deathbed, “Methinks I'm becoming a god.”

Â

Roamin' the Romans

The Colosseum could seat around 50,000. It featured easy and well-designed exits, a retractable roof (an awning on ropes and pulleys that took a crew of 1,000 to raise), and something that beats even monster truck ralliesâthe ability to be flooded for mock naval battles. Today, you can peer down into the labyrinth of underground passages and cages under the floor and gaze up the 160 feet to the nosebleed section, where women and lower classes were allowed to sit.

Vespasian faced turmoil and resistance in the provinces, but handled them well. He put down the remains of the rebellions, reformed and spaced out legions along the borders, and moved to separate recruits from their own territory. In doing so, he increased Rome's border defenses and contributed to a process of homogenization of the Empire. He went far beyond his predecessors in also strengthening provincial

participation by extending citizen rights, promoting urbanization, and adding provincials to the senate. He removed some older members and added many more new. While the senate's power continued to decline, the cohesion between Rome, Italy, and the provinces increased.

Vespasian held and was active in numerous consulships and offices such as censor, and fully promoted his sons as his heirs. For this he earned both blame as a shameless dynasty promoter and a measure of relief for providing a clear path for succession. But although he had critics and enemies in the senate and among the upper class, he took most of this in stride and with a degree of indulgence. He showed less favor toward the criticisms of intellectuals. He expelled Stoic and Cynic philosophers, whose criticisms he considered irritating and superfluous, from Rome.

When Vespasian died, he left the principate prepared for a smooth transition of power. Titus not only had his father's powers and

imperium,

but was praetorian prefect. This gave him an unobstructed path to the principate.

Titus succeeded to the principate without issue, but there were some misgivings. He was reputed to be a wild character, immoderate, and, as praetorian prefect, had a nasty reputation for doing Vespasian's dirty work no matter what it took. He also had a thing going with Bernice, a Judaean royal whom he met while finishing up for dad in Palestine. Another eastern seductress? Shades of Cleopatra! Titus brought her to Rome in 75, and they were momentarily a public item, but she was such a political and public relations nightmare that Vespasian made Titus break things off and send her back to Judaea. Rome virtually groaned when Titus came to power, however inevitable it was.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

Not much remains from Titus's short reign, but in the Roman Forum, you can view his spectacular triumphal arch still standing and complete with reliefs depicting his triumph and the spoils of Jerusalem.

But to everyone's surprise, Titus was a much different emperor than heir. He was kind, compassionate, fair, intelligent, and deferential to the traditions of his office. Vesuvius blew up and destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum; Titus heaped disaster relief on and personally visited the area. Another huge fire swept through Rome; Titus rebuilt it bigger and better and put on public celebrations. A plague swept into Italy; Titus again organized and provided public relief and aid. His generosity and moderation stunned his critics, and his response to this series of disasters earned him public adulation. Then, only slightly two years after taking office, he suddenly died. His enigmatic dying remark, “I have made only one mistake,” led to centuries of speculation.

Rome was unprepared for Titus's death. He had no children and no designated heir. But his brother, Domitian, filled the gap and had himself proclaimed emperor by the praetorians before Titus had turned cold. This was the second time Domitian had moved to grab the opportunity for power. He had come out of hiding after Vitellius's death to take on a role in ruling Rome before his father arrived. He took this role a bit

too

seriously and too much to heart, however, and for this it looks like Vespasian and Titus kept him somewhat under wraps. But with dad and big brother gone, Domitian was

princeps

at last.

Domitian has a terrible reputation, worse than he probably deserves. He appears to have administered the Empire remarkably well. He completed his father's and brother's projects, put on extravagant games, suppressed rebellions in Germany, expanded and solidified Roman holdings along the Rhine, and raised the pay of the legions. Through shrewd, though not popular diplomacy, he made the kingdom of Dacia (modern Rumania) a client kingdom and buffer instead of trying to conquer it. Imperial palaces, roads, and frontier settlements were also constructed throughout the Empire. All this and no harsh taxes, no debasing the currency, and still an Empire in the black.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

In wandering the ruins of the great imperial residences of the Palatine hill, such as Domitian's, you'll realize why we get the word “palace” from the name on the hill on which they were constructed.