The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (40 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Â

Roamin' the Romans

We owe one of the most beloved Roman squares, Piazza Navona, to Domitian. I recommend that you go there at night. Wander among the street artists, have your fortune read, and see Bernini's famous fountain statue recoiling in horror at Boromini's (Bernini's rival) church. As you promenade, you'll recognize that the piazza preserves the outline of Domitian's stadium and the buildings still line the racecourse like spectators.

Domitian was hated for openly acting as an autocrat. Of course, this was basically

true,

but part of the deal with the

princeps

was that you weren't supposed to

act

like it. Domitian never understood that part. He paraded around in royal garb. He built an enormous imperial palace on the palatine and conducted there what amounted to a royal court. He encouraged others to recognize him as

dominus et deus,

lord and god. He treated the senate as inconsequential and subservient.

Domitian recognized that a strong central religion could bring cohesion to a broadening Roman civilization. He championed himself as a defender and center of Roman religion and

Romanitas

(Roman-ness). Impiety, including failing to worship the emperor and imperial gods, became treason. Tradition has it that he persecuted religions, including

Judaism and Christianity, that refused to recognize the emperor as

dominus et deus.

The actual evidence for this is slim, however, and rests mostly on interpretations of the New Testament book of

Revelation

(which has never been an easy text for anyone to interpret).

As time went on, Domitian became increasingly paranoid, saw conspiracies everywhere, and attacked those he suspected. Finally, realizing that they would all be suspected sooner or later, his wife, the praetorians, imperial servants, and high ranking senators conspired against him and murdered him in his bedroom. Rome celebrated and pulled down the autocrat's statues.

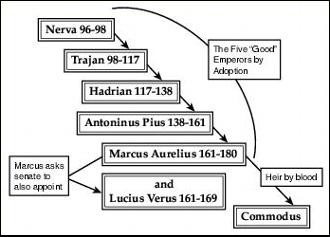

No chaos or uprising followed the assassination of Domitian. The Flavians had left the Empire stable and centered on Rome. There was no question of returning to the Republic, no revolting legions, no rampaging praetorians. There was, however, also no dynasty. Instead, a kind of compromise between traditions came about, whereby an emperor designated a successor by adoption, passing on the office both by heredity and by merit but

not by blood.

This worked remarkably well, and ushered in a period known as the “Five Good Emperors.”

The “good” emperors.

Nerva was an aging senator without an heir who was appointed emperor by the senate following the assassination of Domitian. But Nerva was unable to maintain order. Those who had been repressed by Domitian began to push the envelope while the military, which admired their soldiering (and well-paying) warlord, began to grow discontented.

Finally, revolt broke out. Soldiers forced their way past Nerva and executed Domitian's assassins, whom Nerva was harboring. The end was near, but Nerva made the astute move of adopting the popular and respected governor of Upper Germany, Marcus Ulpius Trajanus (Trajan), as an heir in 97. This quelled problems and earned Nerva the title

Pater Patriae

(father of his country) as well as the right to live out the rest of his life in peace and security. It wasn't very longâNerva died just a few months later.

Trajan has been one of Rome's most influential and popular emperors. His 20-year rule was marked by military conquest, good government, good relations with the senate, and an overall sense of grandeur, competence, and maturity.

Trajan, a distinguished and imposing figure, looked the part of the

princeps,

and he played it, too. In time, the highest wish of the senate for a new emperor was “more fortunate than Augustus and even better than Trajan.” This reputation remained into the Middle Ages, when Dante allowed him, of all the emperors, into paradise in

The Divine Comedy.

Trajan was the first emperor born in the provinces. He was of Spanish origin (born near Seville), and through good family connections and personal merit, he rose under Vespasian and Domitian to become the governor of Lower Germany. He was so secure in his position that he did not go directly to Rome after Nerva's death but spent two years making sure Rome's northern defenses were secure before proceeding to the capitol.

Â

When in Rome

By Trajan's time, Italy was struggling economically and population was on the decline. To help, Trajan instituted

alimenta,

public funds that were used to subsidize education and food for needy families and children. Funds were acquired from a system in which large landowners pledged small portions of land as collateral for government loans. The small interest payments that they paid for these loans funded the alimenta.

His arrival in Rome was impressive: Tall, handsome, and rugged, Trajan looked the part of a world commander. He treated the senate with deference and respect and pursued popular and progressive public politics. Of these, most point to his

alimenta,

subsidized public assistance for poor children. Trajan was also a prolific builder in both Rome and the provinces. In Rome, he is chiefly known for his magnificent Forum, market, and his spectacular Trajan's Column, a remarkable complex of public buildings that demonstrates the intertwining of Roman conquest, culture, and economy. Trajan celebrated his Dacian conquests by building an enormous forum, basilica, and two public libraries from which visitors could view his famous carved column (still standing). He also built, overlooking the civic buildings, a magnificent market that featured imports from the Roman world. There, Romans could not only see the grandeur that the spoils of war could bring, but they could also purchase

food, spices, and luxury goods coming from these far-flung conquests. Besides Rome, you can find other projects such as his harbor at Ostia, his remarkable villa (near Civitavecchia), roads, and bridges throughout the Empire.

The remains of Trajan's magnificent market and forum.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

Trajan's Column is one of the most famous monuments of Rome. Presented by the senate as a part of Trajan's Forum (see Chapter 1, “Dead Culture, Dead Language, Dead Emperors: Why Bother?”), it served both as a burial chamber and a monumental record of his achievements. The 100-foot column was cut with a spiraling relief and was intended to be viewed from the library balconies that graced either side of the column as a part of the Forum. The relief shows scenes from Trajan's Dacian campaigns and is a source of both artistic wonder and historical information. A spiral staircase inside the column leads up to the top, where a statue of Trajan originally stood. The statue of St. Peter replaced Trajan's in the late 1500s.

Trajan is chiefly known, however, for his military exploits. He fought wars in Dacia (modern Rumania), Armenia, and Mesopotamia. While his settlement of Dacia stood, his conquests in the east were less secure. He realized at least some of Caesar's and

Antony's Alexander-esque ambitions and pressed the Roman border all the way to the Persian Gulf. There he reportedly sighed, “Had I been younger I would have liked to have gone to India too.” But Trajan's eastern conquests were crumbling behind him. Revolts in Judaea and Mesopotamia, Parthian troubles in Armenia, and other eastern turmoil forced him to return. While trying to deal with these problems, he fell ill. He put Publius Aelius Hadrianus (Hadrian) in charge of the east and left for Rome but suffered a stroke and died without boarding the ship.

Hadrian rose through his connections with Trajan's family, and eventually his friendship with Trajan and Trajan's wife, Plotina. When Trajan died, it appears that things were not quite settled. Plotina sent the senate documents confirming Hadrian's adoption as successor, but these had her signature. To this day no one knows exactly how, or by whom, Hadrian became emperor.

Hadrian suffered by having to follow in Trajan's immensely popular footsteps and having to clean up messes that Trajan's policies and exploits left behind. While Trajan's exploits were legendary, they left Rome virtually depleted while defenses cracked at the edges. Hadrian decided to return to an Augustan approachâto a Rome that was non-expansionist in temperament, stable, and with firm and delineated borders. He gave up some of Trajan's conquests in the east, which upset both military and senatorial expansionists. He worked to firm up Roman borders with projects such as the famous

Hadrian's Wall

built between England and Scotland.

Â

Veto!

Not

all

reports of Trajan were glowing. While he and his wife, Pompeia Plotina, had sterling reputations, there were reports of dark eddies under the still waters of the imperial family. Trajan, for example, reportedly was a bit too fond of wine and young boys; Plotina is said to have encouraged Hadrian to marry into Trajan's family behind Trajan's back, and to have forged documents confirming him as Trajan's heir.

Â

When in Rome

Hadrian's Wall

was an 80-mile wall roughly separating England from Scotland. Built first of dirt and timber, and then stone, the wall featured forts, supply roads, and settlements at regular intervals along its way. It is not only a major tourist attraction and important archeological site but features beautiful walks along its ruins.

Hadrian was an admirer of all things Greek. He started a trend for the next several emperors by sporting a beard, studying Greek literature, and patronizing the city of Athens. Unpopular at Rome, Hadrian traveled the Empire extensively, visiting every corner of the realm. He founded cities, including an attempt at restoring Jerusalem as Aelia

Capitolina with a temple of Jupiter on the site of Solomon's temple. This attempt resulted in a major Jewish revolt under Simon Bar-Kochba, which was suppressed at an enormous cost and loss of life. He also founded a city in Egypt in honor of his young companion, Antinous, who died under mysterious circumstances while traveling with Hadrian in Egypt.