The Good, the Bad and the Unready (61 page)

Read The Good, the Bad and the Unready Online

Authors: Robert Easton

Louis the

Louis the

Sun King

Louis XIV, king of France, 1638–1715

When Louis ascended the throne at the age of five, a party of grumbling nobles orchestrated violent unrest – known as ‘le Fronde’ –against his quasi-regent Cardinal Mazarin. In celebration of the defeat of these upstart aristocrats, Mazarin commissioned a ballet entitled

Le Ballet de la Nuit

, in which Louis danced the central role of the Rising Sun, while the princes of the Fronde were portrayed as rebellious divinities making obeisance to their prancing monarch. In so doing, Louis employed dance as a weapon of state and also won his nickname of ‘le Roi Soleil’.

Later, Louis delighted in appearing at various balls in his opulent courts as Apollo, the god of the sun, and incorporated the sun as part of his heraldic device, thus conveying to one and all his personal brilliance and that of the Bourbon dynasty. By the end of his reign, however, political clouds were forming over a nation whose place in the sun was increasingly unsure.

Fulk the

Fulk the

Surly

Fulk IV, count of Anjou, 1043–1109

Disgruntled at inheriting little more than the Chateau of Vihiers from his uncle Geoffrey Martel while his elder brother ‘Geoffrey the Bearded’ received the province of Anjou, Fulk ‘le Rechin’ swiftly imprisoned Geoffrey and claimed the region as his own.

Still dissatisfied with his lot, he then spent much of his life in battle against local barons and the forces of the duke of Normandy. Life hit rock bottom for the surly count, however, when the enormously fat Philip the

AMOROUS

‘ran’ off with his wife.

Sweet Nell

Sweet Nell

see

Eleanor the

WITTY

Ivan the

Ivan the

Terrible

Ivan IV, tsar of Russia, 1530–84

When Ivan was only three his father died, leaving control of Russia in the hands of the senior members of the aristocracy known as boyars. For ten years these boyars utterly neglected their prince, to the extent that he became a beggar in his own palace. He was washed, dressed in fine clothes and put on display only when it was necessary to show a visiting dignitary that Russia was stable. The only person to whom little Ivan could turn was his nurse, Agrafena, and when she was forcibly removed to a convent he was utterly lost and alone – more ‘Ivan the Traumatized’ than ‘Ivan the Terrible’. Such an upbringing may go some way to explain his dark deeds of later life.

His terrible rule began on 29 December 1543 when he summoned the boyars together, berated them for their inhumanity and had their leader thrown into an enclosure with a pack of starving hounds. The dogs immediately set upon the screaming man and ate him. The large crowd of Muscovites who witnessed the event were deeply impressed, and the cowering boyars acknowledged that Ivan had complete power.

It is said that Ivan’s troops bestowed upon him the term of ‘Grozny’, meaning ‘the Terrible’ or more accurately ‘the Awesome’, after their victory over the Tatar stronghold of Kazan in 1562. Be that as it may, Ivan is popularly known as ‘the Terrible’ for his barbarism. Below are just some of the acts for which he is held responsible.

• He hurled dogs and cats from the Kremlin walls just to watch them suffer.

• He roamed the streets knocking down old people at will.

• He raped women, and disposed of his victims by having them hanged, thrown to bears or buried alive.

• He imprisoned his uncle in a dungeon and left him to starve.

• He had a peasant woman strip naked and then used her as target practice.

• He drowned a host of beggars en masse in a lake.

• He forced a boyar to sit on a barrel of gunpowder and then blew him to bits.

• He happened across his pregnant daughter-in-law in her underwear and beat her with his staff because he considered her attire indecent.

• He boiled his treasurer alive in a cauldron.

• He killed his own son in a fit of temper.

His most heinous crime of all was ordering the massacre of the 60,000 citizens of Novgorod. After the archbishop was sewn up in a bearskin and hunted to death by a pack of dogs, the ‘Oprich-niki’, Ivan’s black-uniformed secret police, embarked on their wholesale slaughter. Observers reported that so many bodies clogged the Volkhov River that it overflowed its banks.

As well as a callous heart, Ivan also had a calloused forehead, a condition caused by his throwing himself before icons and banging his head on the floor in acts of extreme devotion. He deeply loved his wife, Anastasia, calling her his ‘little heifer’, and when she died after a lingering disease, he underwent an emotional collapse and repeatedly hit his head on the floor in full view of the court. In 1584, after a forty-year reign of terror, Ivan was settling down to play a game of chess when he suddenly collapsed and died.

Attila the

Attila the

Terror of the World

see

Attila the

SCOURGE OF GOD

James the

James the

Thistle

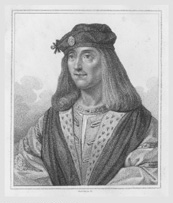

James IV, king of Scotland, 1473–1513

Although James was rather easily duped into signing away valuable crown lands (most notably to the Campbell and Gordon clans), he was a truly popular king, and it was his very shortcomings as a ruler – his fun-loving spirit and generosity – that won the hearts of his people.

James the

Thistle

James ascended the throne when he was only fifteen, and dancing, hunting and hawking were the preferred pastimes in the court of the young monarch. Carefree with his money and extravagant with his wine bill, he was also a great religious enthusiast. He ate no meat on Wednesdays and Fridays, refused to mount a horse on Sundays and would not allow anything to interfere with his annual pilgrimage to the remote shrines of St Ninian and St Duthac. All this deeply impressed the courtier-poet William Dunbar, who, in his work

The Thrissil and the Rose

, dubbed his king ‘Thrissil’, or ‘Thistle’, after the national flower, and the young queen Margaret, daughter of Henry the

ENGLISH SOLOMON

(

see

ENGLISH EPITHETS

), ‘that sweit meik Rois’.

Whatever James did, he did with energy. Internationally he improved his nation’s position within European politics, while domestically he improved the education system and licensed Scotland’s first printers. Passionately interested, meanwhile, in dentistry and surgery, he once paid a man fourteen shillings to be allowed to extract one of the man’s teeth, and another nearly two pounds to be allowed to let his blood.

More moonstruck than military, James died at the battle of Flodden Field whenhe accompanied his spearmen in a reckless

downhill charge, his costly heroism helping to make him one of Scotland’s most popular monarchs of all time. Perhaps more pathetic than James’s sorry death, however, was that of his son, Alexander, the archbishop of St Andrews, a man so short-sighted that in order to read he had to hold a book at the end of his nose. Out of love and loyalty to his earthly father, he joined him on the battlefield. One hopes and expects that his demise was swift.