Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (10 page)

Between 378 and 382, Gratian rejects the old Roman religion, while Theodosius tries to legislate brotherhood and unity

F

IVE MONTHS AFTER

the death of Valens, the emperor Gratian appointed a new ruler for the east: Flavius Theodosius, who now became Emperor Theodosius I. Gratian’s younger brother Valentinian II, technically his co-emperor, was still only seven years old, and he needed a competent colleague.

The greatest threat to the east, Persian invasion, was diminishing. In 379, Shapur the Great of Persia died after a spectacularly long reign of nearly seventy years and was succeeded by his elderly brother Ardashir II, who was more concerned with hanging on to his crown than with invading foreign parts. Instead, both Gratian and Theodosius turned to ensure that the Roman empire would survive. The Goths to the north were growing steadily more powerful, but the more immediate problem was the ongoing tendency of the Roman coalition to pull apart from the inside; Constantine’s hope for an empire held together by faith was still unrealized.

Gratian, a devout Christian, soon found himself at odds with the Roman senators who still held to the traditional Roman state religion. Four years after the Battle of Hadrianople, Gratian made it quite clear to the Senate that he would not allow the Roman gods to undermine the empire’s Christian faith. In 382, he removed the Altar of Victory from the Senate building in Rome. It had stood there since Augustus’s defeat of Antony and Cleopatra four hundred years before, as tribute to the goddess of victory. The senators protested, but Gratian stood firm. He also removed the title pontifex maximus, high priest of the Roman state religion, from his list of titles; and when the sacred robes were brought to him, as was traditional, for him to put on, he refused to don them. In doing so he was rejecting not just the Roman gods, but the entire Roman past; as Zosimus points out with asperity, the kings of Rome had accepted the title pontifex maximus since the days of Numa Pompilius a thousand years before. Even Constantine had put on the robes. “If the emperor refuses to become Pontifex,” one of the priests is said to have muttered at the time, “we shall soon make one.”

1

Whether Gratian’s power could survive the hostility of the senators remained to be seen.

To the east, Theodosius was forced to deal with the destructive power of Christian division. Arguments about the Arian take on the divinity of Christ, as opposed to the Nicene understanding, had spread to the lowest levels of society. “Everywhere throughout the city is full of such things,” complained the bishop Gregory of Nyssa, in a sermon preached at Constantinople,

the alleys, the squares, the thoroughfares, the residential quarters; among cloak salesmen, those in charge of the moneychanging tables, those who sell us our food. For if you ask about change, they philosophise to you about the Begotten and the Unbegotten. And if you ask about the price of bread, the reply is, “The Father is greater, and the Son is subject to him.” If you say, “Is the bath ready?”, they declare the Son has his being from the non-existent. I am not sure what this evil should be called—inflammation of the brain or madness or some sort of epidemic disease which contrives the derangement of reasoning.

2

To restore the empire to the vision of Christian unity that Constantine had seen so clearly, Theodosius turned to law. He used the legal structures of the ancient Roman state to support the Christian religion (never mind that it was diametrically opposed to the ancient Roman traditions); he used the power of the emperor to shape the Christian faith so that the Christian faith could shape the empire. The interweaving of the two traditions continued to change both of them in ways that would prove impossible to undo.

Two years after taking the throne, in the year 380, Theodosius declared that Nicene Christianity was the one true faith, and threatened dissenters with legal penalties. In doing so, he called into being a single, unified,

catholic

(the word means universal, applying to all humankind) Christian church. “He enacted,” writes the Christian historian Sozomen, “that the title of ‘Catholic Church’ should be exclusively confined to those who rendered equal homage to the Three Persons of the Trinity, and that those individuals who entertained opposite opinions should be treated as heretics, regarded with contempt, and delivered over to punishment.”

3

Long before Theodosius, Christian bishops had distinguished the

ecclesia catholica

from the

haeretici

, the heretics, those who were by belief outside of the stream of true Christian doctrine. But never before had “heretic” been defined by law. Now, “heretic” had a legal definition: someone who did not hold to the Nicene Creed. “All of the people shall believe in God within the concept of the Holy Trinity,” the law declared, “and take the name catholic Christians. Meeting places of those who do not believe shall not be given the status of churches, and such people may be subject to both divine and earthly retribution.”

4

Theodosius actually believed that he could legislate his subjects into believing only in a Nicene-defined deity. He was a clever politician, but his theological reasoning was often naive. Sozomen, for example, writes that when Theodosius convened a church council the following year (381), as a follow-up to the issuing of the law, he brought together the “presidents of the sects which were flourishing” so that they could discuss their differences: “for he imagined that all would be brought to oneness of opinion, if a free discussion were entered into, concerning ambiguous points of doctrine.”

5

This was wildly optimistic, and as anyone who has ever been involved in church work could predict, it didn’t work. But Theodosius soldiered on. Now that his law had been passed, he could start enforcing uniformity on a practical level. He took all of the meeting places and churches of the non-Nicene Christians and handed them over to the Nicene bishops, a material gain for those fortunate priests. He threatened to expel heretics who insisted on preaching from the city of Constantinople and to confiscate their land. He didn’t always carry through on these threats; Sozomen remarks, approvingly, that although he had enacted severe punishments for heresy into law, the punishments were often not applied: “He had no desire to persecute his subjects; he only desired to enforce uniformity of view about God through the medium of intimidation.”

6

Theodosius was finding that it was easier to announce unity than to actually create it. In many ways, the Goths were easier to deal with than heretics; all he had to do was kill them.

While he was convening councils and making doctrine, Theodosius was also directing a fight against Gothic invasion. The Goths had become such a problem that Gratian, in the west, had agreed to transfer the most Goth-infested part of his western empire—three dioceses in the central province of Pannonia—over to the eastern empire so that Theodosius would be responsible for driving the Goths out.

8.1: The Transfer of Pannonia

Unfortunately the army was not quite strong enough to take on this extra task, so Theodosius managed to beef it up with an innovative strategy: he recruited barbarians from some regions to fight against barbarians in other regions. He would hire Goth mercenaries from Pannonia, transfer them over to Egypt, and then bring Roman soldiers from Egypt over to Pannonia to fight other Goths. The definition of “Roman soldier,” like the definition of “Roman,” was becoming increasingly nebulous, even while Theodosius managed to make the definition of “Christian” more restrictive.

7

The thinness of the line between Roman and barbarian became more obvious in 382, when, after four years of fighting against the Goths, Theodosius decided that too much energy was going to the war, and made a peace treaty with them instead. The treaty allowed them to exist, within the borders of the Roman empire, under their own king. The Gothic king would be subject to him as emperor, but the Goths themselves would not have to answer to any Roman official; and when they fought for Rome, they would do so as allies, rather than as Roman soldiers in regular Roman army units subject to regular Roman officers.

8

By 382, Theodosius could claim that he had reduced the chaos in the eastern part of the empire to order. The Christian church was unified, the Goths were at peace, all was right with the world.

But all of Theodosius’s solutions had the appearance, not the reality, of victory. In fact, the Goths were not subdued. Arianism (not to mention a score of other heresies) was not dead. The Christians of the empire were not united. And even the leadership of Theodosius’s newly created Catholic church was in debate. As part of his church council in 381, Theodosius had announced that the bishop of Constantinople was equal to the bishop of Rome in authority, “because Constantinople is the New Rome.”

9

This law might be on the books, but in 382—even as Theodosius celebrated his victories—the bishops of the older cities, the traditional centers of Christianity, were objecting to the exaltation of the relatively young bishopric in Constantinople.

So did the bishop of Rome, who called his own council in Rome in 382 and announced that the bishop of Rome was the leader of all other bishops, including the upstart at Constantinople. The churchmen in Rome agreed, and the bishop of Rome ordered his secretary, a young man named Jerome, to record the decision. The Roman council also agreed that Jerome, who was good with languages, should start working on a new Latin translation of the Scriptures.

This was a direct response to the attempt to make the Greek-speaking east equal to the west; the council at Rome had now declared that Latin, the language of the west, was the proper language for Scripture (and the proper language for public worship as well). Theodosius had declared all Christians to be one, but the eastern and western halves of his catholic church were beginning to pull apart.

Between 383 and 392, a Spaniard becomes king of the Britons, and Theodosius discovers that he has underestimated the power of the church

I

N

383,

THE

R

OMAN ARMY

in Britain rebelled and proclaimed a new emperor: Magnus Maximus, their general.

At first Magnus Maximus possessed only the loyalty of the troops in Britannia; he was, in effect, the king of the Britons—despite being a Roman citizen and a Spaniard by birth. But it seems likely that he had exercised a king-like power in isolated Britannia for some years. His name pops up in Welsh legends, where he is known as Macsen Wledig, a half-legendary figure who stars in the epic

Breuddwyd Macsen

. In the tale, Macsen Wledig is in Rome, ruling as emperor, when he dreams of a beautiful maiden who must become his wife; he searches for her and eventually crosses the water to Britain, where he finds her and marries her. He then spends seven years building castles and roads in Britain—so long that a usurper back in Rome takes his throne from him.

The faint whisper of historical truth in this myth is that Magnus Maximus did in fact claim the title “Emperor of Rome” while still in Britain, and undoubtedly had spent a good portion of his time as a Roman commander building roads and developing the Roman infrastructure on the island. Possibly Magnus Maximus also allowed tribes from the western island (modern Ireland) to settle on the western coast of Britain, a combination of cultures that produced the country of Wales; this would explain his appearance in Welsh tales of the country’s origin, where he shows up so often that John Davies calls him a “ubiquitous lurker.”

1

At this point Britain had not yet been Christianized. The Roman army in Britannia was thoroughly committed to the old Roman state religion, discontented that both senior Roman emperors, Gratian and Theodosius, were Christian. Maximus, on the other hand, was unabashedly Roman in his beliefs; when the army acclaimed him, he announced his loyalty to Jupiter and then gathered up his forces and headed for Gaul, hoping to possess the throne of the west in fact and not simply in name.

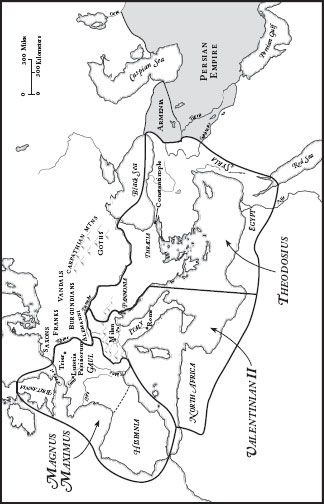

9.1: The Empire in Thirds

An echo of this campaign appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s thoroughly unreliable

History of the Kings of Britain

, in which King Arthur sails with his army to Gaul and fights against the Roman tribune who governs it. In that version of the tale, Arthur triumphs (after laying waste to the countryside) and sets up a royal court at the old Roman fortress town Lutetia Parisiorum, on the Seine. In the real world, Magnus Maximus marched into Gaul and arrived at Lutetia Parisiorum, where Gratian met him in battle. Part of Gratian’s army—the part that wanted an emperor who worshipped Jupiter rather than the Christian God—defected to Maximus’s side, and the remainder were defeated. Gratian fled and died not long afterwards, either captured and killed by Maximus’s soldiers or assassinated by one of his own officers.

2

This left Maximus in control of Gaul, and he declared himself emperor of Gaul and Hispania as well as Britannia. The empire was divided into three: Magnus Maximus in the far west, Theodosius in the east, and Gratian’s younger brother and former co-emperor, Valentinian II, still hanging on to power in Italy and North Africa.

Now that he was in control of part of the western mainland, Maximus sent Theodosius an official message, emperor to emperor, suggesting that they be allies and friends. The invasion had happened too quickly for Theodosius to block it, and now that it was a fait accompli, he decided that it would be prudent to accept Maximus’s offer. He and Maximus were old acquaintances, as it happened; they had fought together in Britannia as young men. He agreed to recognize Maximus as a legitimate emperor, and for four years, the three emperors ruled side by side, with Theodosius as the senior Augustus. “Nevertheless,” writes Zosimus, “he was at the same time privately preparing for war, and endeavouring to deceive Maximus by every species of flattery.”

3

Preparing for war involved negotiating with the Persians; Theodosius didn’t want to head west and immediately find his eastern border under attack. Ardashir II, the elderly brother of the great Shapur, had been deposed by the Persian noblemen at court after four years of inefficiency; now Shapur’s son Shapur III sat on the throne. The issue most likely to cause another war between the two empires was control of Armenia, so Theodosius sent an ambassador to Shapur III’s court to negotiate a settlement.

4

The ambassador was a Roman soldier named Stilicho, who had been born in the northern parts of the empire. His mother was Roman, but his father was a Vandal—a “barbarian,” a native of the Germanic peoples who lived just north of the Carpathian Mountains. Unlike the Goths, the Vandals were not a present trouble to the Roman empire. Nevertheless, in the eyes of many Romans, Stilicho carried with him the taint of the barbarian. The historian Orosius, who disliked him, used his parentage to condemn him; he was “sprung from the Vandals, an unwarlike, greedy, treacherous, and crafty race.”

5

But Theodosius trusted him, and in return Stilicho—at that time still in his twenties—performed an impressive negotiating feat. In 384, Shapur III agreed to divide the control of Armenia between the two empires. The western half of Armenia would be ruled by a Roman-supported king, the eastern half by a king loyal to Persia. Theodosius was grateful; when Stilicho returned, Theodosius promoted him to general and married him to the fourteen-year-old princess Serena, Theodosius’s own niece and adopted daughter.

The treaty with the Persians allowed Theodosius to continue his preparations for war with the western usurper. Meanwhile, Magnus Maximus was making plans to move east, against the court of Valentinian II. Maximus wanted to be true emperor of the west, and as long as Valentinian II was still in Italy, his legitimacy was shadowed.

Valentinian II was only fifteen, and the real power in Italy was held by his generals and his mother, Justina. In 386, Justina gave Maximus the excuse he needed to invade Italy. She was herself an Arian Christian, which put her at odds with the orthodox bishop of Milan, Ambrose. They had quarrelled off and on for years, but in 386, Justina (by way of her son) issued an imperial order commanding Ambrose to hand over one of the churches of Milan to the Arians so that they could have their own meeting place. Ambrose indignantly refused, upon which Justina upped her demands and asked for another, more central and more important church instead: the New Basilica.

She sent officials to the Basilica on the Friday before Palm Sunday (the beginning of Holy Week, the most important week in the church calendar), while Ambrose was teaching a small group of converts in order to prepare them for baptism. The officials started to change the hangings in the church; Ambrose carried on, apparently ignoring them.

This invasion of the church by imperial officials infuriated the Nicene Christians in Milan, and they gathered at the church to protest. The demonstrations spread. Holy Week was taken up with riots in the streets, armed arrests of citizens (“The prisons were filled with tradesmen,” Ambrose wrote to his sister later), and a larger and larger turnout of imperial soldiers. Ambrose couldn’t get out of the Basilica because it was surrounded by soldiers, so he staged an involuntary sit-in with his congregants. He passed the time by preaching that the church could never be controlled by the emperor; the church was in the image of God, it was the body of Christ, and since Christ was fully God (a slap at the Arians), the church was itself one with the Father.

6

Finally, Valentinian II intervened and ordered the soldiers out. But he was unhappy with Ambrose’s power, even more than with the defeat of the Arian takeover: “You would deliver me up in chains, if Ambrose bade you,” he snapped at his court officials, and Ambrose was deeply afraid that the next thing coming down the pike would be an accusation of treason.

When Maximus got wind of the unrest, he announced his plans to attack. “The pretext,” writes the church historian Sozomen, “was that he desired to prevent the introduction of innovations in the ancient form of religion and ecclesiastical order…. He was watching and intriguing for the imperial rule in such a way that it might appear as if he had acquired the Roman government by law, and not by force.”

7

Considering that Maximus had originally campaigned in the name of Jupiter, his new pose as defender of the Nicene faith undoubtedly rang a little hollow. But this shows the extent to which Christianity, in the late Roman empire, had already become the language not just of power but of legitimacy. Maximus didn’t merely want to be emperor. He wanted to be a

real

emperor, a lawful emperor, and in order to have any chance to assert this, he had to align himself with the Christian church. Even while Ambrose preached that the church was separate from the power of the emperor, the emperors wielded the church as a weapon against each other.

As Maximus marched across the Alps towards Milan, Theodosius marched west with his own army—and Valentinian II and Justina fled from Italy into Pannonia, taking with them Valentinian’s sister Galla and leaving Milan open to Maximus and his armies. When Theodosius arrived in Pannonia, Justina offered to give Theodosius her daughter Galla if he would drive Maximus out. Theodosius accepted; Galla was reputedly very beautiful, but in addition the marriage related him, the rough ex-soldier from Hispania, to the Valentinian dynasty.

He then marched the rest of the way to Milan, sending ahead of him plenty of information about the size and lethal skill of his army. Possibly Maximus had not expected Theodosius to actually leave the eastern border and come all the way west. In any case, by the time Theodosius reached Milan, Maximus’s men were so thoroughly intimidated that his own soldiers took Maximus captive and handed him over. The war was resolved without a single battle. Theodosius executed Maximus, bringing an end to the reign of the first king of the Britons. He also sent an assassin, his trusted general Arbogast, to find Maximus’s son and heir. Arbogast found the young man in Trier and strangled him.

8

The whole invasion had worked out pretty well for Theodosius. He now had a whole new level of power over the west; he was Valentinian’s brother-in-law and deliverer, and he staged a triumphal procession to Rome in which he took center stage. He then departed, taking his beautiful young wife with him and leaving his general Arbogast (now back from strangling Maximus’s son) to be Valentinian’s new right-hand man.

Like Stilicho, Arbogast was of “barbarian” descent. His father was a Frank, and so although he could pursue a shining career in the army, he had no hope of ascending to the imperial throne. Theodosius’s most trusted aides tended to be half (or more) barbarian; they could not challenge their master for the crown. Arbogast was an experienced soldier by this time, and Valentinian II, accustomed to being dominated, was helpless against him. Arbogast took over the administration of the empire, reporting directly to Theodosius in the east, while Valentinian II sat in his imperial throne as little more than a figurehead.

In essence, Theodosius now had control over the entire empire, and he turned his attention again to the project of unification. On his return to Constantinople, he began to issue the Theodosian Decrees—a set of laws designed to bring the whole Roman realm into line with orthodox Christian practice. The first decree, issued in 389, was a strike at the very root of the relationship between the old Roman religion and the Roman state: Theodosius declared that the old Roman feast days, which had always been state holidays, would now be workdays instead. Official holidays then, as now, were ways of laying out the mythical foundations of a nation, of pointing citizens towards the high points of the past that helped to define the present. Theodosius was not just Christianizing the empire; he was beginning to rewrite its history.

In this he was slightly out of step with the mood of the west. Back in Rome, the senators had already applied three times to the imperial court in Milan, asking that the traditional Altar of Victory (removed by Gratian) be reinstalled in the Senate. The appeals had been led by Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, the prefect (chief administrative officer) of the city of Rome. He begged Valentinian to preserve the customs of the past: “We ask the restoration of that state of religion under which the Republic has so long prospered,” he wrote. “Permit us, I beseech you, to transmit in our old age to our posterity what we ourselves received when boys. Great is the love of custom.”

But even more central to the argument of Symmachus was his understanding of faith; he could not see why it was necessary, for the triumph of Christianity, to do away with all reminders of the old Roman religion. His appeal continues:

Where shall we swear to observe your laws and statutes? by what sanction shall the deceitful mind be deterred from bearing false witness? All places indeed are full of God, nor is there any spot where the perjured can be safe, but it is of great efficacy in restraining crime to feel that we are in the presence of sacred things. That altar binds together the concord of all, that altar appeals to the faith of each man, nor does any thing give more weight to our decrees than that all our decisions are sanctioned, so to speak, by an oath…. We look on the same stars, the heaven is common to us all, the same world surrounds us. What matters it by what arts each of us seeks for truth?

9