Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (7 page)

This was a serious matter, as the bishop of Rome was probably the most influential priest in the entire Christian church. The bishops of Rome considered themselves the spiritual heirs of the apostle Peter, and they considered Peter to be the founder of the Christian church. For some decades already, the bishop of Rome had claimed the right to make decisions that were binding on the bishops of other cities.

*

This privilege was far from unchallenged; the bishops of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem, all cities that could boast a Christian community as old as the Christian community in Rome, resented the assumption that Rome was the center of the Christian world. Nevertheless, all of the bishops could agree that Constantius ought not to appoint and remove

any

bishop at will. Constantius, paying no attention to their objections, called a church council of his own in 359 and announced at it that Arian Christology was now orthodox. Neither Roman bishop—either the deposed one or the newly appointed one—was invited.

None of the churchmen were pleased with this high-handedness, which seems to have stemmed from real theological conviction (certainly Constantius reaped no political benefits by meddling in church affairs in this way). Constantius fell into disfavor, particularly with churchmen in the western half of the empire, where anti-Arian sentiment was strongest. So when Constantius, alarmed by Julian’s swelling popularity, demanded that Julian in the west reduce his armed force by sending some of his troops eastward, Julian banked on his cousin’s growing unpopularity in the west and his own stellar reputation and refused. The army on the Rhine, backing him up, elevated him to the post of co-emperor.

This put the empire back under two emperors, a situation that neither man found bearable. But Julian was not anxious to launch an out-and-out attack on Constantius, who (after all) had Constantinople and most of the east on his side. For his part, Constantius didn’t dare leave the eastern borders and march west against Julian. The Persian threat was too immediate; Shapur’s army was already approaching the Roman borders.

The Roman soldier Ammianus Marcellinus, who later wrote a history of the Roman wars with Persia, had been sent secretly into Armenia (now Persian-controlled) to spy on the Persian advance. From the top of a cliff, he spotted the armies advancing: “the whole circuit of the lands filled with innumerable troops,” he remembers, “with the king leading the way, glittering in splendid attire.”

14

The Roman army burned the fields and houses in front of the approaching enemy to prevent them from finding food, and made a stand at the Euphrates river; but the Persians, advised by a Roman traitor who had gone over to their side, made a detour north through untouched fields and orchards.

The Romans pursued them, and the two armies finally met at the small walled city of Amida, in Roman territory. The city was good for defense, since (as Ammianus Marcellinus explains) it could only be approached by a single narrow pass, and the Romans took up a defensive position in the gap. But a detachment of Persian cavalry had managed, without the Romans’ knowledge, to get around behind the city, and the Romans found themselves jammed into the pass, attacked from both sides. Ammianus, fighting in the middle of the throng, was trapped there for an entire day: “We remained motionless until sunrise,” he writes, “…so crowded together that the bodies of the slain, held upright by the throng, could nowhere find room to fall, and that in front of me a soldier with his head cut in two, and split into equal halves by a powerful sword stroke, was so pressed on all sides that he stood erect like a stump.”

15

Finally Ammianus and the other surviving Roman soldiers made it into the city. The Persians attacked the walls with archers and with war elephants: “frightful with their wrinkled bodies and loaded with armed men, a hideous spectacle, dreadful beyond every form of horror.” Amida withstood the siege for seventy-three days. The streets were stacked with “maggot-infested bodies,” and plague broke out within the walls. The defenders kept the wooden siege-engines and the elephants at bay with burning arrows, but finally the Persians heaped up mounds of earth and came over the walls. The inhabitants were slaughtered. Ammianus escaped through a back gate and found a horse, trapped in a thicket and tied to its dead master. He untied the corpse and fled.

16

Constantius was forced to surrender not only Amida but also at least two other fortresses, a handful of fortified towns, and eastern land. Meanwhile, Julian still threatened in the west. Suspended between two hostile powers, Constantius didn’t dare turn his back on one to attack the other.

A fever solved his dilemma. On October 5, 361, Constantius died from a virus, his body so hot that his attendants could not even touch him. Julian was sole emperor, by default, of the entire Roman empire.

Between 361 and 364, Julian tries and fails to restore the old Roman ways

A

S SOON AS

J

ULIAN

took control of Constantinople, it became clear that his Christian education had been entirely unsuccessful. He had been in correspondence for some years with the famous rhetoric teacher Libanius, who guided him in his study of Greek literature and philosophy, and had been in secret sympathy with the old religion of Rome for most of his adult life.

Now he openly announced himself as an opponent of Christianity. His baptism, he said, was a “nightmare” that he wished to forget. He ordered the old temples, many of which had been closed under the reign of the Christian emperors, to be reopened. And he decreed that no Christian could teach literature; since a literary education was required for all government officials, this would eventually have guaranteed that all Roman officials had received a thoroughly Roman education.

1

It also meant that the Christians in the empire would become chronically undereducated. Most Christians refused to send their children to schools where they would be indoctrinated in the ways of the old Roman religion. Instead, Christian writers began to try to create their own literature, to be used in their own schools: as A. A. Vasiliev writes, they “translated the Psalms into forms similar to the odes of Pindar; the Pentateuch of Moses they rendered into hexameter; the Gospels were rewritten in the style of Plato’s dialogues.”

2

Most of this literature was so substandard that it disappeared almost at once; very little has survived.

This was an odd kind of persecution—and one that reveals Julian’s essential likeness to his Gupta counterparts, kings he would never meet. Julian was a conservative. He wanted to bring back the glorious past. He wanted to draw a line clearly between Roman and non-Roman; it was a disappearing line, thanks to Constantine’s decision to unite his empire by faith rather than by their pride in “Romanness,” and Julian wanted it back. He wanted to rebuild the wall of Roman civilization against not only the Christians but all who did not share this same tradition. “You know well,” Libanius had written to him, back in 358, “that if anyone extinguishes our literature, we are put on a level with the barbarians.” To have no literature was to have no past. To have no past was to be a barbarian. As far as Julian was concerned, Christians were both barbarians and atheists; they had no literature, and they did not believe in the Roman gods.

3

Julian did realize that the old Roman religion would need updating if it were to compete with the unifying power of the Christian church. So he pursued two strategies. First, he stole the most useful elements of the Christian church for the Roman religion. He studied the hierarchy of the Christian church, which had proved relatively good at holding far-flung congregations together, and reorganized the Roman priesthood in the same way. And he ordered Roman priests to model the worship of the Roman gods on the popular Christian services, importing discourses (like sermons) and singing into the old Roman rituals. Worship of Jupiter had never looked more like worship of Jesus.

His second strategy was more subtle. He allowed all of the Christian churchmen who had been banished at various times for being on the wrong side of the Nicene-Arian debate to return. He knew they were incapable of getting along; and sure enough, serious theological arguments were soon breaking out. It was the flip side of Constantine’s methods; Julian was capitalizing on Christianity’s power to divide, not its power to unify.

4

For all of this, he earned himself the nickname “Julian the Apostate.”

Ironically, his political problems forced him to recognize the rights of barbarians to Roman privileges at the same time that he was restoring the old ideas of Romanness. Unable to fight simultaneously with Shapur on his east and with invading Germanic tribes to the north, he had no choice but to allow the Germanic tribes of the Franks to settle in northern Gaul as

foederati

, Roman allies with many of the rights of Roman citizens.

With the threat of the Franks averted, Julian launched a Persian campaign. In 363, he marched east with eighty-five thousand men—not only Romans, but also Goths (Germanic tribes who had been

foederati

since the days of Constantine) and Arabs, who were anxious to get their revenge on Shapur for his shoulder-tearing. He also brought traditional soothsayers and Greek philosophers with him, in place of the priests and tabernacle Constantine had planned to use. The two groups complicated the enterprise by falling out with each other; the soothsayers insisted that the omens were bad and the army should withdraw, while the philosophers countered that such superstitions were illogical.

5

At the Persian border, he divided his forces and sent thirty thousand of his men down the Tigris, himself leading the rest down the Euphrates by means of ships, constructed on the banks of the river where it ran through Roman territory and launched downstream. The idea was that they would meet at Ctesiphon, the Persian capital (on the east bank of the Tigris, a bit south of Baghdad) and perform a pincer move on the Persians.

According to Ammianus, the Roman fleet was an amazing sight: fifty war galleys and a thousand supply ships with food and bridge-building materials. Shapur, alarmed by the size of the approaching army, left his capital city as a precaution, so when Julian arrived he found the king gone. The armies built bridges across the Tigris to the east bank and laid siege to Ctesiphon anyway. The siege dragged on and on. Shapur, safely away from the action, rounded up additional men and allies from the far corners of his empire and returned to fight the besieging army. Julian was forced to retreat back up the Tigris, fighting the whole way and struggling to keep his men alive; the Persians had burned all of the fields and storehouses in their path.

The retreat took all spring. By early summer, the Roman soldiers hadn’t yet made it back to their own border. They were starving, wounded, and constantly harassed by the Persians who pursued them. One June day, during yet another Persian ambush, Julian was struck by a Persian spear that lodged in his lower abdomen. He was carried back to camp, where he slowly bled to death: one of only three Roman emperors to fall in battle against a foreign enemy.

*

Ammianus Marcellinus, who was with the army, describes a beautifully classical death: Julian, resigned to his fate, carrying on a calm discussion about the “nobility of the soul” with two philosophers until he died. The Christian historian Theodoret insists that Julian died in agony, recognizing too late the power of Christ and exclaiming, “Thou hast won, O Galilean!”

6

Of these two equally unlikely accounts, the Christian version comes closest to describing the situation. Julian’s army was stranded, besieged, and in need of leadership and rescue. After a bit of arguing and milling around, the officers dressed one of their generals, a dignified and kindly man named Jovian, in the imperial robes and proclaimed him emperor.

7

Jovian, aged thirty-three, was a Christian.

From this point on, Christian emperors would rule the empire. The old Roman religion would never again dominate the Roman court. Not that this brought an end to the striving; it simply meant that the battle between past and the present, the old Rome and the new empire, went underground.

Jovian was a pragmatist. Instead of fighting, he put on his crown and asked Shapur for a parley. The treaty, once concluded, allowed the Roman army to go home in peace. In exchange, Jovian agreed to hand over to the Persians all Roman land east of the Tigris, including the Roman fortress of Nisibis. Nisibis would become the center of Persian assaults against the Roman frontier; it never returned to western control.

8

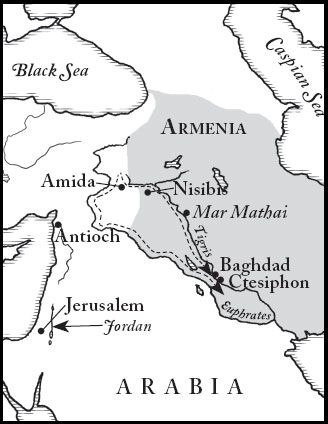

5.1: The Persian Campaign

The army limped westward under Jovian’s command, to face scorn and fury from the Romans back home. The treaty was condemned as shameful, a disgrace to Rome, an unacceptable conclusion to Julian’s bold and disastrous campaign.

Jovian himself never even returned to Constantinople. Once he was back in Roman land, he paused at the city of Antioch and started to work at once to chart a middle way. He revoked all of Julian’s anti-Christian decrees, but rather than replacing them with equally restrictive decrees against the Roman religion, he declared religious toleration. He was, himself, unabashedly faithful to the Nicene Creed, but he had decided to remove religion from the center of the empire’s politics. Christian, Greek, Roman: all would have equal rights to worship and to take part in government.

9

But it was too late. Religious and political legitimacy—religious and political claims to rule—were intertwined at the empire’s center. A very strong and charismatic emperor (which the nice-minded Jovian was not) might have managed to hold on to power and proclaim religious tolerance at the same time, but Jovian’s political authority was already weak, thanks to the unpopular treaty with Persia. His only hope for hanging on to power was to use religious authority in its place, establishing a strict religious orthodoxy as the center of his power.

His refusal to do so meant that he had no authority at all. In 364, eight months after his elevation to the imperial crown, he died in his tent while he was still making his slow way back towards the eastern capital. Reports of the cause were suspiciously varied; he was said to have died of fumes from a badly vented stove, from indigestion, from a “swollen head.” “So far as I know,” Ammianus remarks, “no investigation was made of the death.” The Roman throne lay open for the next claimant.

10

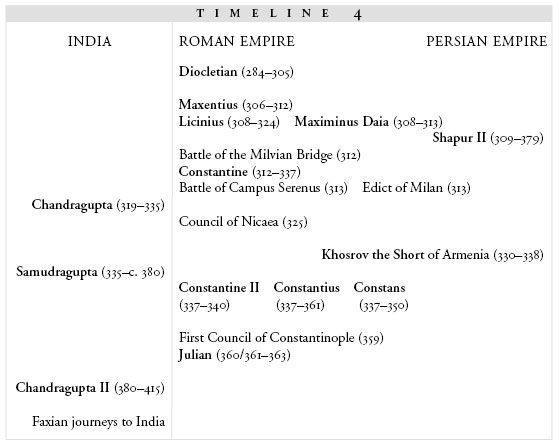

TIMELINE

5

INDIA | ROMAN EMPIRE | PERSIAN EMPIRE |

| | Shapur II |

| Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312) | |

| Constantine | |

| Battle of Campus Serenus (313) Edict of Milan (313) | |

Chandragupta | Council of Nicaea (325) | |

| | Khosrov the Short |

Samudragupta | | |

| Constantine II | |

| First Council of Constantinople (359) | |

| Julian | |

| Jovian | |

Chandragupta II | | |

Faxian journeys to India | | |