Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (4 page)

Arius, who served in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, had been gathering followers and vexing his bishop,

*

who had finally excommunicated him. This created a potentially serious and major breach, one that might well separate a large group of Christians from the main body of the Christian believers. Constantine, learning of the split, sent a letter to Egypt strongly suggesting that the two men sit down and work out their differences: “Restore me then my quiet days, and untroubled nights, that the joy of…a tranquil life may henceforth be my portion,” he wrote.

13

But neither the bishop nor Arius was willing to yield, and in desperation Constantine called together a council of church leaders to settle the question. He first intended to have the council at the city of Nicomedia, but a severe earthquake unsettled the city while the bishops were on their way to the meeting; buildings collapsed, hundreds died where they stood, and flames from hearths and braziers were flung into the dry frames of the houses, where the blaze spread so rapidly that the city became, in the words of Sozomen, “one mass of fire.”

14

Such a sudden and disastrous event suggested to many that God was not pleased with the coming council, and the travelling bishops halted in their tracks and sent urgent inquiries to the emperor. Would he call off the council? Should they proceed?

Reassured by the churchman Basil that the earthquake had been sent not as judgment but as a demonic attempt to keep the church from meeting and settling its questions, Constantine replied that the bishops should travel instead to Nicaea, where they arrived in late spring of 325, ready to parley.

Settling theological questions by way of council was not a new development for Christianity; since the time of the apostles, the Christian churches had considered themselves smaller parts of a whole, not individual congregations. But never before had an emperor, even a tolerant one, taken the step of summoning a church council on his own authority.

15

In 325, at Nicaea, the Christian church and the government of the west clasped hands.

One might wonder why Constantine, who didn’t have any trouble reconciling his belief in Apollo with his professed Christianity, cared about the exact definition of Christ’s Godness. In all likelihood, his interest in this case wasn’t theological but practical: to keep the church from splitting apart. A major breach would threaten Constantine’s vision of Christianity as a possible model for holding together a disparate group of people in loyalty to an overarching structure. If the overarching structure cracked, the model would be useless.

Which probably explains his decision to be anti-Arian; taking the temper of the most influential leaders, he realized that the most powerful bishops disagreed with Arius’s theology. Arianism essentially created a pantheon of divinities, with God the Father at the top and God the Son as a sort of demiurge, a little lower in the heavenly hierarchy. This was anathema to both the Jewish roots of Christianity and the Greek Platonism which flourished in most of the eastern empire.

*

Directed by their leading bishops and by the emperor himself to be anti-Arian, the assembled priests at Nicaea came up with a formulation still used in Christian churches today: the Nicene Creed, which asserts the Christian belief in “one God, the Father almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible”:

And in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the only-begotten Son of God,

begotten of the Father before all worlds,

God of God,

Light of Light,

Very God of Very God,

begotten, not made,

being of one substance with the Father

by whom all things were made.

It was a formulation that, in its emphasis on the divinity of Christ, shut the door firmly on Arianism.

And it had the imperial stamp on it. In laying hold of Christianity as his tool, Constantine had altered it. Constantine’s ineffable experience of the divine at the Milvian Bridge had proved useful in the moment. But ineffable experiences are notoriously bad at binding together any group of people in common purpose for a long time, and the empire, now tenuously held together by a spider-web linkage, needed the Christian church to be more organized, more orderly, and more rational.

Christians, in return, would have had to be more than human to resist what Constantine was offering: the imprint of imperial power. Constantine gave the church all sorts of advantages. He recognized Christian priests as equal to priests of the Roman religion, and exempted them from taxes and state responsibilities that might interfere with their religious duties. He also decreed that any man could leave his property to the church; this, as Vasiliev points out, in one stroke turned “Christian communities” into “legal juridical entities.”

16

Further tying his own power to the future of the church, he had also begun construction of a new capital city, one that from its beginning would be filled with churches, not Roman temples. Constantine had decided to move the capital of his empire, officially, from Rome and its gods to the old city of Byzantium, rebuilt as a Christian city on the shores of the pass to the Black Sea.

17

All at once Christianity was more than an identity. It was a legal and political constituency—exactly what it had not been when Constantine first decided to march under the banner of the cross. The church, like Constantine’s empire, was going to be around for a little while; and like Constantine, it had to take care for its future.

After his condemnation at the Council of Nicaea, Arius took to his heels and hid in Palestine, in the far east of the empire. Arianism did not disappear; it remained a strong and discontented underground current. In fact, Constantine’s own sister became a champion of Arian doctrines, rejecting her brother’s command to accept the Nicene Creed as the only Christian orthodoxy.

18

She may have been motivated by bitterness. In 325, within months of the Council of Nicaea, Constantine broke his promise of clemency to her husband Licinius and had him hanged. Unwilling to leave any challengers to his throne alive, Constantine also sent her ten-year-old son, his own nephew, to the gallows.

Four years later, he officially dedicated the city of Byzantium as his new capital, the New Rome of his empire. Disregarding the protests of the Romans, he had brought old monuments from the great cities of the old empire—Rome, Athens, Alexandria, Antioch, Ephesus—and installed them among the new churches and streets. He ordered Roman “men of rank” to move to his new city, complete with their households, possessions, and titles.

19

He was re-creating Rome as he thought it should be, under the shadow of the cross. The emblem of Daniel in the lion’s den, the brave man standing for his God in the face of a heathen threat, decorated the fountains in the public squares; a picture of Christ’s Passion, in gold and jewels, was embossed on the very center of the palace roof.

20

By 330 Constantine had succeeded in establishing one empire, one royal family, one church. But while the New Rome celebrated, the old Rome seethed with resentment over its loss of status; the unified church Constantine had created at Nicaea was held together only by the thin veneer of imperial sanction; and Constantine’s three sons eyed their father’s empire and waited for his death.

TIMELINE

1

ROMAN EMPIRE

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

Between 313 and 402, the Jin cling to the Mandate of Heaven, while the northern barbarians aspire to seize it

A

S

C

ONSTANTINE WAS UNITING

his empire in the west, the eastern empire of the Jin

*

was disintegrating. Its emperor, Jin Huaidi, had been forced into captivity and servanthood. In 313, at the age of twenty-six, he was pouring wine for his masters at a barbarian feast, and his life hung by a thread.

The Jin empire was a young one, barely fifty years old. For centuries, the old Han dynasty had held the Chinese provinces together in one sprawling and unified whole, the eastern parallel to the Roman empire in the west. But by

AD

220, the Han had fallen to rebellion and unrest. The empire fractured apart into thirds, and the Three Kingdoms that took over from the Han—the Cao Wei, the Shu Han, and the Dong Wu—were unstable, shifting and battling for control.

The northernmost of the Three Kingdoms, the Cao Wei, was controlled by its generals; the kings who sat on the Cao Wei throne were young and easily cowed, and did as they were told. In 265, the twenty-nine-year-old general Sima Yan decided to claim the Cao Wei crown for himself. His entire life he had watched as army men pulled the puppet-king’s strings. The commanders of the Cao Wei army, including his father and his grandfather, had led in the conquest of the neighboring kingdom of the Shu Han, reducing the Three Kingdoms to two; Cao Wei dominated the north, but its generals remained crownless.

2.1: The Three Kingdoms

Unlike them, Sima Yan did not intend to spend his career as puppet-master. He already had power; what he craved was legitimacy, the

rightful

power to command—the title that accompanied the sword.

According to the

Three Kingdoms

, the most famous account of the years after the fall of the Han, Sima Yan buckled on his sword and went to see the emperor: the teenager Wei Yuandi, grandson of the kingdom’s founder. “Whose efforts have preserved the Cao Wei empire?” he asked, to which the young emperor, suddenly realizing that his audience chamber was crowded with Sima Yan’s supporters, answered, “We owe everything to your father and grandfather.” “In that case,” Sima Yan said, “since it is clear that you can’t defend the kingdom yourself, you should step aside and appoint someone who can.” Only one courtier objected to this; as soon as the words left his mouth, Sima Yan’s supporters beat him to death. The

Three Kingdoms

is a romance, a fictionalized swashbuckling account written centuries later; nevertheless, it reflects the actual events surrounding the rise of the Jin dynasty. Wei Yuandi agreed to Sima Yan’s plans; Sima Yan built an altar, and in an elaborate, formal ceremony, Wei Yuandi climbed to the top of the altar with the seal of state in his hands, gave it to his rival, and then descended to the ground a common citizen.

That day the entire body of officials prostrated itself once and again below the Altar for the Acceptance of the Abdication, shouting mightily, “Long live the new Emperor!”

1

The ceremony had transformed Sima Yan into a

rightful

ruler, a divinely ordained emperor, holder of the Mandate of Heaven. Wei Yuandi, stripped of the Mandate, went back to ordinary life. He died some years later in peace.

Sima Yan took the royal name “Jin Wudi” and became the founder of a new dynasty: the Jin. By 276, he was confident enough in his grasp on his empire to launch a takeover bid against the remaining kingdom, the Dong Wu.

The power of the Dong Wu had been dwindling under an irrational king who had become unbearably cruel; his favorite game was to invite a handful of palace officials to a banquet and get them all drunk, while eunuchs stationed just outside the door wrote down everything they said. The next morning he would summon the officials, hungover and wretched, to his audience chamber and punish them for every incautious word.

2

By the time the Jin armies arrived at the Dong Wu capital of Jianye, his subjects were ready to welcome their conqueror.

This story, which comes from the Jin’s own official chronicles, probably tells us more about Jin Wudi than about his opponent. Jin Wudi, desperate for legitimization, knew his history. He knew that for thousands of years, dynasties had risen through virtue and fallen through vice. Emperors ruled by the will of Heaven, but if they grew tyrannical and corrupt, the will of Heaven would raise up another dynasty to supplant them. Jin Wudi wanted a greater justification than force to help him dominate the Dong Wu.

Nevertheless, force brought him into the city. The Jin armies, planning on making the final push into Jianye by river, found their way blocked by barriers of iron chain. So they sent flaming rafts, piled high with pitch-covered logs, floating down into the barriers; the chains melted and snapped, and the Jin flooded into Jianye.

3

The tyrannical emperor surrendered. The era of the Three Kingdoms was ended; by 280, all of China was united again under the Jin.

4

This was the empire which lasted barely half a century.

Jin Wudi died in 290, leaving as heir an oldest son who was, in the words of his disgusted subjects, “more than half an idiot.” Unwisely, he also left behind twenty-four other sons (he had overindulged himself in wives and concubines), all of whom had been awarded royal titles of one kind or another.

5

At once, war broke out. Wife, father-in-law, step-grandfather, uncles, cousins, and brothers all jockeyed to control the half-wit who sat on the throne.

The chaos that swallowed up the Jin empire from 291 to 306 was later known as the Rebellion of the Eight Princes. In fact, far more than eight royal relatives were jockeying for control, but only eight of them managed to rise to the position of regent for the idiot emperor, a position that gave them the crown de facto. In the middle of all this, the emperor himself survived until 306. Finally, an unknown assassin brought his miserable life to an end with a plateful of poisoned cakes.

6

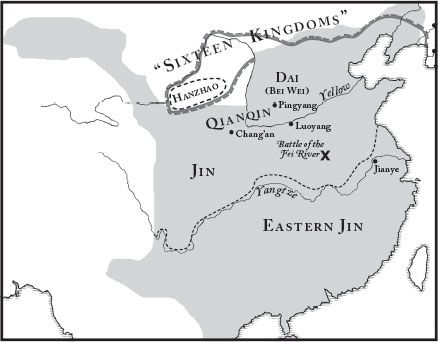

2.2: The Jin

After his death, a faction supporting his youngest half-brother managed to get its candidate crowned. The new emperor, Jin Huaidi, was an intelligent, educated, and thoughtful young man, not particularly interested in self-indulgence or tyranny. But he was fighting against rough odds. The Rebellion of the Eight Princes had moth-eaten his empire into fragility, and various claimants to the throne were still lurking nearby, with their own personal armies behind them. There was also danger to the north, where a slew of tiny states ruled by warlords aspired to conquer the greater kingdom below them. The Chinese to the south gave these the collective name “Sixteen Kingdoms,” although their number was fluid.

In the end, it was one of the Sixteen Kingdoms, the Hanzhao, that brought the frayed Jin empire down. Hanzhao armies pushed constantly south, raiding Jin land. By 311, they had reached the walls of the Jin capital Luoyang itself.

Luoyang, stripped and wrecked by civil war, was not well equipped to withstand siege. The Jin armies fought a dozen desperate engagements with the Hanzhao invaders outside the walls; but the people inside were starving, and the gates were finally thrown open. Jin Huaidi fled, hoping to reach the city of Chang’an and take refuge there. Instead, he was captured on the road and hauled back as a prisoner of war to the new capital city of the swelled Hanzhao kingdom, Pingyang.

7

There, the Hanzhao ruler, Liu Cong, dressed him as a slave and forced him to serve wine to officials at royal banquets. Jin Huaidi spent two miserable years as a palace slave, but visitors to the court were shocked to see the man who held the Mandate of Heaven forced into servitude. That the Mandate had come to him by way of threat and manipulation made no difference; its mantle still covered him. An upswell of feeling that Jin Huaidi should be freed began to trouble Liu Cong’s court. Liu Cong, who had already proved that his sword was stronger than Jin Huaidi’s mandate, responded by putting the Jin emperor to death.

8

Three years later, he marched down to Chang’an, where the surviving Jin court had gathered, and conquered it.

The brief dominance of the Jin had ended. But the Jin name itself survived. Sima Rui, another Jin relative, was in command of a sizable Jin force quartered at the city of Jianye. He was the strongest man around, and in 317, after a gap in the Jin emperorship, his soldiers pronounced him emperor. He took the imperial name “Jin Yuandi,” and although his reign was short, he was succeeded by his son and grandsons in an unbroken imperial line that ruled from Jianye over a shrunken southeastern domain.

*

Neither the Hanzhao nor any of the other Sixteen Kingdoms tried to bring a final end to the Jin, possibly because the land south of the Yangtze didn’t lend itself to fighting on horseback (the preferred method of northerners, inherited from their nomadic ancestors). As far as the Jin were concerned, the river now marked the boundary between

real

China and the northern realm of the barbarians. Despite the short history of their empire, the Jin emperors attempted to prove that the Mandate was theirs by keeping the torch of ancient Chinese civilization burning. The court at Jianye modelled itself on the old traditions of the Han, bringing back rituals of ancestor worship that had faded during the chaotic decades of civil war and playing host to Confucian scholars who taught, in the traditional manner, that the enlightened man was he who recognized his duties and carried them out faithfully. Holding on to Confucius’s promise that a virtuous ruler will gain more and more authority over his people (moral authority, Confucius taught, would roll out from the righteous ruler like wind, bending his subjects to obedience as wind bends grass), the Jin emperors struggled to live rightly and follow the ancient rituals. “Guide the people by virtue,” the

Analects

had promised, “keep them in line by rites, and they will…reform themselves.”

9

The promise that virtuous government would always triumph held the Jin court together, even in the face of defeat by the northern barbarians.

“B

ARBARIAN

” was a moveable term; the harder the Jin fought to distinguish themselves from the uncivilized warriors to the north, the more those uncivilized warriors wanted to be just like the Jin.

In the latter half of the fourth century, the most ambitious of the northern “barbarians” was Fu Jian, chief of the Qianqin. Fu Jian had aspirations to be truly Chinese. He had founded Confucian academies in his state and had reformed the government of his kingdom so that it was run along Chinese lines; his capital city was the ancient Chinese capital of Chang’an; his chief minister, the ruthless Wang Meng, was Chinese.

10

As soon as he inherited the rule of the Qianqin, in 357, Fu Jian began to launch attack after attack on the nearby Sixteen Kingdoms. After twenty years of fighting, he had absorbed most of them, almost uniting the north of China under a single crown; and he intended to absorb the Jin as well. In 378, the northern army of the Qianqin marched south against the Jin borders. The Jin emperor, Jin Xiaowudi, fought back, but over the next few years he lost his border cities, one at a time. By 382, Fu Jian of the Qianqin was ready to make a final assault. He marched south with an enormous force: according to the chroniclers of his day, 600,000 foot-soldiers and 270,000 cavalry, historical hyperbole that nevertheless points to an army of unprecedented size.

11

With a much smaller force, Jin Xiaowudi came north to meet him and put up a desperate defense of the core of the Jin empire. The armies clashed at the Fei river (now dry), in an epic encounter that became one of the most famous in Chinese history: the Battle of the Fei River. “The dead were so many,” says one account, “that they were making a pillow for each other on the ground.”

12