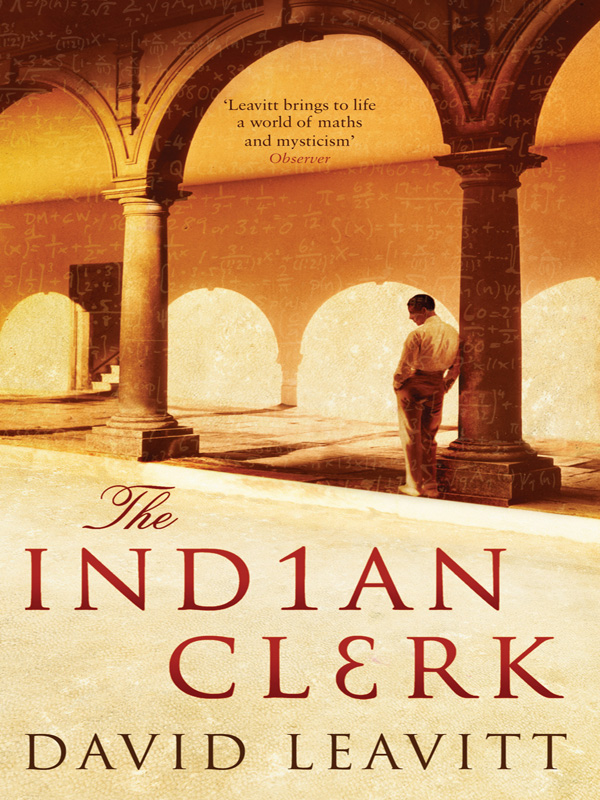

The Indian Clerk

Authors: David Leavitt

THE INDIAN CLERK

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Fiction

Family Dancing

The Lost Language of Cranes

Equal Affections

A Place I've Never Been

While England Sleeps

Arkansas

The Page Turner

Martin Bauman; or, A Sure Thing

The Marble Quilt

Collected Stories

The Body of Jonah Boyd

Nonfiction

Florence, A Delicate Case

The Man Who Knew Too Much:

Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer

The Indian Clerk

a novel

David Leavitt

First published in Great Britain 2008

Copyright © David Leavitt

This electronic edition published 2009 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of David Leavitt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-40880-682-1

www.bloomsbury.com/davidleavitt

Visit

www.bloomsbury.com

to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

Archimedes will be remembered when Aeschylus is forgotten, because languages die and mathematical ideas do not. "Immortality"

may be a silly word, but probably a mathematician has the best chance of whatever it may mean.

—G. H. Hardy,

A Mathematician's Apology

CONTENTS

T

HE MAN SITTING next to the podium appeared to be very old, at least in the eyes of the members of his audience, most of whom

were very young. In fact he was not yet sixty. The curse of men who look younger than they are, Hardy often thought, is that

at some moment in their lives they cross a line and start to look older than they are. As an undergraduate at Cambridge, he

had regularly been mistaken for a schoolboy up for a visit. As a don, he had regularly been mistaken for an undergraduate.

Now age had caught up with him and then outrun him, and he seemed the very embodiment of the elderly mathematician whom progress

has left behind. "Mathematics is a young man's game"—he himself would write these words in a few years time—and he had had

a better run of it than most. Ramanujan had died at thirty-three. These days admirers smitten with Ramanujan's legend speculated

as to what he might have achieved had he lived longer, but it was Hardy's private opinion that he wouldn't have achieved much.

He had died with his best work behind him.

This was at Harvard, in New Lecture Hall, on the last day of August, 1936. Hardy was one of a mass of scholars reeled in from

around the world to receive honorary degrees on the occasion of the university's tercentenary. Unlike most of the visitors,

however, he was not here—nor, he sensed, had he been invited—to speak about his own work or his own life. That would have

disappointed his listeners. They wanted to hear about Ramanujan.

While the smell of the room was in some ways familiar to Hardy—a smell of chalk and wood and stale cigarette smoke—its sounds

struck him as peculiarly American. How much more noise these young men made than their British counterparts! As they rummaged

in their briefcases, their chairs squeaked. They murmured and laughed with one another. They did not wear gowns but rather

jackets and ties—some of them bow ties. Then the professor who had been given the task of introducing him—a youth himself,

whom Hardy had never heard of and to whom he had been introduced just minutes before—stood at the dais and cleared his throat,

at which signal the audience quieted. Hardy made certain to show no reaction as he listened to his own history, the awards

and honorary degrees that authorized his renown. It was a litany he had become used to, and which sparked in him neither pride

nor vanity, only weariness: to hear listed all he had achieved meant nothing to him, because these achievements belonged to

the past, and therefore, in some sense, no longer belonged to him. All that had ever belonged to him was what he was doing.

And now he was doing very little.

Applause broke out and he ascended to the dais. The crowd was larger than he had thought at first. Not only was the room full,

there were students sitting on the floor and standing against the back wall. Many of them had notebooks open on their laps,

held pencils poised to write.

(Well, well. And what would Ramanujan think of this?)

"I have set for myself," he began, "a task in these lectures which is genuinely difficult and which, if I were determined

to begin by making every excuse for failure, I might represent as almost impossible. I have to form myself, as I have never

really formed before, and to try to help you to form, some sort of reasoned estimate of the most romantic figure in the recent

history of mathematics . . ."

Romantic.

A word rarely heard in his discipline. He had chosen the word with care, and planned to use it again.

"Ramanujan was my discovery. I did not invent him—like other great men, he invented himself—but I was the first really competent

person who had the chance to see some of his work, and I can still remember with satisfaction that I could recognize at once

what a treasure I had found." Yes, a treasure. Nothing wrong with that. "And I suppose that I still know more of Ramanujan

than anyone else, and am still the first authority on this particular subject." Well, some might dispute that. Eric Neville,

for one. Or, more to the point, Alice Neville.

"I saw him and talked with him almost every day for several years, and above all I actually collaborated with him. I owe more

to him than to anyone else in the world with one exception, and my association with him is the one romantic incident in my

life." He looked at the crowd. Did that ruffle some feathers? He hoped so. Some of the young men glanced up from their note

taking, met his gaze with furrowed brows. One or two, he felt sure, gave him looks of empathy. They understood. Even the "one

exception" they understood.

"The difficulty for me then is not that I do not know enough about him, but that I know and feel too much and cannot be impartial."

Well, he had said it. That word. Although, of course, neither was in the room—one was dead, with the other he had been out

of touch for decades—from the back row, Gaye and Alice met his gaze. Gaye looked, for once, approving. But Alice shook her

head. She did not believe him.

Feel.

T

HE LETTER ARRIVES the last Tuesday in January 1913. At thirty-five, Hardy is a man of habit. Every morning he eats his breakfast,

then takes a walk through the Trinity grounds—a solitary walk, during which he kicks at the gravel on the paths as he tries

to untangle the details of the proof he's working on. If the weather is fine, he thinks to himself,

Dear God, please let it rain,

because I don't really want sun pouring through my windows today; I

want gloom and shadows so that I can work by lamplight.

If the weather is bad, he thinks,

Dear God, please don't bring back the sun

as it will interfere with my ability to work, which requires gloom and

shadow and lamplight.

The weather is fine. After half an hour, he goes back to his rooms, which are good ones, befitting his eminence. Built over

one of the archways that lead into New Court, they have mullioned windows through which he can watch the undergraduates passing

beneath him on their way to the backs. As always, his gyp has left his letters stacked on the little rosewood table by the

front door. Not much of interest today, or so it appears: some bills, a note from his sister, Gertrude, a postcard from his

collaborator, Littlewood, with whom he shares the odd habit of communicating almost exclusively by postcard, even though Littlewood

lives just on the next court. And then—conspicuous amid this stack of discreet, even tedious correspondence, lumbering and

outsize and none too clean, like an immigrant just stepped off the boat after a very long third-class journey—there is the

letter. The envelope is brown, and covered with an array of unfamiliar stamps. At first he wonders if it has been misdelivered,

but the name written across the front in a precise hand, the sort of hand that would please a schoolmistress, that would please

his sister, is his own: G. H. Hardy, Trinity College, Cambridge.

Because he is a few minutes ahead of schedule—he has already read the newspapers at breakfast, checked the Australian cricket

scores, shaken his fist at an article glorifying the advent of the automobile—Hardy sits down, opens the envelope, and removes

the sheaf of papers that it contains. From some niche in which she has been hiding, Hermione, his white cat, emerges to settle

on his lap. He strokes her neck as he begins to read, and she digs her claws into his legs.

Dear Sir,

I beg to introduce myself to you as a clerk in the Accounts Department of the Port Trust Office at Madras on a salary of only

£20 per annum. I am now about 23 years of age. I have had no University education but I have undergone the ordinary school

course. After leaving school I have been employing the spare time at my disposal to work at Mathematics. I have not trodden

the conventional regular course which is followed in a University course, but I am striking out a new path for myself. I have

made a special investigation of divergent series in general and the results I get are termed by the local mathematicians as

"startling."

He skips to the end of the letter—"S. Ramanujan" is the author's name—then goes back and reads the rest. "Startling," he decides,

does not begin to describe the claims the youth has made, among them this: "Very recently I came across a tract by you styled

Orders of Infinity

of which I find a statement that no definite expression has been as yet found for the number of prime numbers less than any

given number. I have found an expression which very nearly approximates to the real result, the error being negligible." Well,

if that's the case, it means that the boy has done what none of the great mathematicians of the past sixty years has managed

to do. It means that he's improved on the prime number theorem. Which

would

be startling.

I would request you to go through the enclosed papers. Being poor, if you are convinced that there is anything of value I

would like to have my theorems published. I have not given the actual investigations nor the expressions that I get but I

have indicated the lines on which I proceed. Being inexperienced I would very highly value any advice you give me. Requesting

to be excused for the trouble I give you.

The trouble I give you!

Hardy nudges Hermione, much to her annoyance, off his lap, then gets up and moves to his windows. Beneath him, two gowned

undergraduates stroll arm in arm toward the archway. Watching them, he thinks of asymptotes, values converging as they near

a sum they will never reach: a half foot closer, then a quarter foot, then an eighth . . . One moment he can almost reach

out and touch them, the next—whoosh!—they're gone, sucked up by infinity.

Now

there's a divergent series for you.

The envelope from India has left a curious smell on his fingers, of soot and what he thinks might be curry. The paper is cheap.

In two places the ink has run.

This is not the first time that Hardy had received letters from strangers. For all its remoteness from the ordinary world,

pure mathematics holds a mysterious attraction for cranks of all stripes. Some of the men who have written to Hardy are genuine

lunatics, claiming to have in their hands formulae pointing to the location of the lost continent of Atlantis, or to have

discovered cryptograms in the plays of Shakespeare indicating a Jewish conspiracy to defraud England. Most, though, are merely

amateurs whom mathematics has fooled into believing that they have found solutions to the most famous unsolved problems.

I have completed the long-sought proof to

Goldbach's Conjecture

—Goldbach's Conjecture, stating simply that any even number greater than two can be expressed as the sum of two primes.

Needless to say I am loath to send my actual proof, lest it fall

into the hands of one who might publish it as his own . . .

Experience suggests that this Ramanujan falls into the latter category.

Being

poor

—as if mathematics has ever made anyone rich!

I have not given

the actual investigations nor the expressions that I get

—as if all the dons of Cambridge are waiting with bated breath to receive them!

Nine dense pages of mathematics accompany the letter. Sitting down again, Hardy looks them over. At first glance, the complex

array of numbers, letters, and symbols suggests a passing familiarity with, if not a fluency in, the language of his discipline.

Yet there is something off about the way the Indian uses that language. What he is reading, Hardy thinks, is the equivalent

of English spoken by a foreigner who has taught the tongue to himself.

He looks at the clock. Quarter past nine. He's fifteen minutes behind schedule. So he puts the letter aside, answers another

letter (this one from his friend Harald Bohr in Copenhagen), reads the latest issue of

Cricket,

completes all the puzzles on the "Perplexities" page of the

Strand

(this takes him—he times it—four minutes), works on the draft of a paper he is writing with Littlewood, and, at one precisely,

puts on his blue gown and walks over to Hall for lunch. God, as he hoped, has disregarded his prayer. The sun is glorious

today, warming his face even as he must shove his hands into his pockets. (How he loves cold, bright days!) Then he steps

inside Hall, and its gloom muffles the sun so thoroughly his eyes don't have time to adjust. Mounted on a platform above the

roar of two hundred undergraduates, watched over by portraits of Byron and Newton and other illustrious old Trinitarians,

twenty or so dons sit at high table, muttering to one another. A smell of soured wine and old meat hovers. There is an empty

seat to Bertrand Russell's left, and Hardy takes it, Russell nodding at him in greeting. Then a prayer is read in Latin; benches

scrape, waiters pour wine, the undergraduates begin to eat lustily. Littlewood, across the table from him and five places

to the left, has become caught up in conversation with Jackson, an elderly classics don—a pity, as Hardy wants to talk with

him about the letter. But perhaps it's just as well. Given some time to think, he might realize it's all nonsense, and spare

himself coming off as an idiot.

Although the Trinity menu is written in French, the food is decidedly English: poached turbot, followed by a lamb cutlet,

turnips and cauliflower, and a steamed pudding of some sort in a curdling custard sauce. Hardy eats little of it. He has very

strong opinions about food, of which the strongest is a detestation of roast mutton that dates back to his days at Winchester,

when it seemed that there was never anything else on the menu. And turbot, in his opinion, is the roast mutton of the fish

world.

Russell seems to have no problem with the turbot. Although they are good friends, they don't much like each other—a condition

of friendship Hardy finds to be much more usual than is usually supposed. For the first few years that he knew him, Russell

wore a bushy mustache that, as Littlewood noted, lent to his face a deceptively dim and mild expression. Then he shaved it

off, and his face, as it were, caught up with his personality. Now thick brows, darker than the hair on his head, shade eyes

that are at once intensely focused and remote. The mouth is sharp and slightly dangerous looking, as if it might bite. Women

adore him—in addition to a wife he has a clutch of mistresses—which surprises Hardy, as another of Russell's distinctive features

is acute halitosis. The breadth of his intellect and its vigor—his determination not merely to be the greatest logician of

his time, but to diagnose human nature, to write philosophy, to enter into politics—impresses and also irritates Hardy, for

the voraciousness of such a mind can sometimes look like capriciousness. For instance, in the last couple of years, he has

published not only the third volume of his mammoth

Principia Mathematica,

but also a monograph entitled

The

Problems of Philosophy.

And yet tonight it is neither the principles of mathematics nor the problems of philosophy of which he is speaking. Instead

he is amusing himself (and not amusing Hardy) by laying out—complete with diagrams sketched on a pad—his translation into

logical symbolism of the Deceased Wife's Sister Act, which legalizes the marriage of a widower to his wife's sister; Hardy

all the while keeping his face averted so as not to have to take in Russell's acrid breath. When Russell finishes (at last!),

Hardy changes the subject to cricket: off-spinners and short legs, hooking mechanisms, the injudicious strategies that, in

his opinion, cost Oxford its last game against Cambridge. Russell, as bored by cricket as Hardy is by the Deceased Wife's

Sister Act, helps himself to another cutlet. He asks if there are any new players for the university whom Hardy admires, and

Hardy mentions an Indian, Chatterjee of Corpus Christi. The summer before, Hardy watched him play in the freshman's match

and thought him very good. (Also very handsome—though he does not say this.) Russell eats his

gateau avec creme anglaise.

It is a considerable relief when at long last the proctor utters the final grace, freeing Hardy to escape logical symbolism

and walk over to Grange Road for his daily game of indoor tennis. As it happens, his partner this afternoon is a geneticist

called Punnett, with whom he also sometimes plays cricket. And what does Punnett think of Chatterjee? he asks. "Perfectly

fine," Punnett says. "They take their cricket seriously over there, you know. When I was in Calcutta, I spent hours on the

maidan. We'd watch the young men play and eat the strangest stuff—a sort of puffed rice with a sticky sauce poured over it."

Recollections of Calcutta distract Punnett, and Hardy beats him easily. They shake hands, and he returns to his rooms, wondering

whether it's Chatterjee's playing or his handsomeness—a very European handsomeness that the contrasting dark skin only renders

all the more unexpected—that has really drawn his attention. Meanwhile Hermione is yowling. The bedder has forgotten to feed

her. He mixes tinned sardines, cold boiled rice, and milk in her dish, while she rubs her cheek against his leg. Glancing

at the little rosewood table, he sees that the gyp has delivered another postcard from Littlewood, which he ignores as he

did the last, not because he doesn't care to read it, but because one of the tenets that governs their partnership is that

neither should ever feel obliged to postpone more pressing matters in order to answer the other's correspondence. By adhering

to this rule, and others like it, they have established one of the only successful collaborations in the history of their

solitary discipline, leading Bohr to quip, "Today, England can boast three great mathematicians: Hardy, Littlewood, and Hardy-Littlewood."

As for the letter, it sits where he had left it, on the table next to his battered rattan reading chair. Hardy picks it up.

Is he wasting his time? Better, perhaps, just to toss it in the fire. No doubt others have done so. His is probably just one

name on a list, possibly alphabetical, of famous British mathematicians to whom the Indian has sent the letter, one after

the other. And if the others tossed the letter in the fire, why shouldn't he? He's a busy man. G. H. Hardy hardly

(Hardy hardly)

has time to examine the jottings of an obscure Indian clerk . . . as he finds himself doing now, rather against his will.

Or so it feels.

No details. No proofs. Just formulae and sketches. Most of it loses him completely—that is to say, if it's wrong, he has no

idea how to determine that it's wrong. It resembles no mathematics he'd ever seen. There are assertions that baffle him completely.

What, for instance, is one to make of this?