The Penguin Book of Card Games: Everything You Need to Know to Play Over 250 Games (173 page)

Read The Penguin Book of Card Games: Everything You Need to Know to Play Over 250 Games Online

Authors: David Parlett

elaborate and imaginative rules and conditions.

First appearing in the late eighteenth century in the Baltic

countries, Patience games may have originated as a variety of

fortune-tel ing, along the lines of ‘Loves me, loves me not’, or

‘Tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor…’. Interestingly, Tarots were first used

for fortune-tel ing in the same century, and there is an obvious

resemblance between tarot and patience layouts.

There are hundreds of dif erent

Patiences(Icoveredsome400varieties in The Penguin Book of

Patience), and more continue to be invented, especial y since the

remarkable revival in their popularity caused by their eminent

remarkable revival in their popularity caused by their eminent

suitability for computer play. In order to impose practical

limitations on the size of this section, I have arbitrarily restricted its

contents to competitive Patience games – that is, those that can be

practised by two or more players in competition with one another,

as distinct from solitarily and in competition with the vagaries of

fortune.

Spite and Malice(Cat and Mouse)

2 players, 108 cards

This is a reworking of a late nineteenth-century Continental game

variously cal ed Crapet e, Cripet e, Robuse, Rabouge, Russian Bank

(etc.). Easley Blackwood in his 1970 treatise on the game says he

saw it ‘several years ago’ being played by various schools in various

ways. The fol owing is based on his proposed standard version.

Preliminaries Use two packs of the same size but dif erent back

colours or designs. One contains 52 cards, the other 56 by the

addition of four Jokers. (But three or even two wil suf ice.)

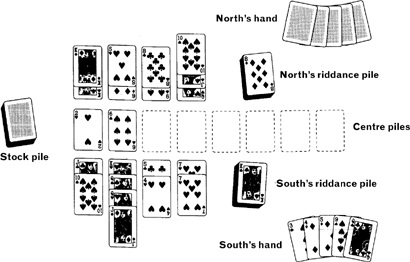

Deal Shuf le the 52-card pack very thoroughly and deal twenty-six

each. Each player’s twenty-six cards form his ‘riddance pile’ and are

placed face down on the table in front of him with the top card

turned face up (the ‘upcard’).

Then shuf le the 56-card pack very thoroughly, deal five each to

form a playing hand, and stack the rest face down as a common

stockpile.

Sequence order is A23456789TJQK. Whoever has the higher

upcard goes first. If equal, bury the upcards and turn the next ones

upcard goes first. If equal, bury the upcards and turn the next ones

up.

Object To play out al 26 cards from one’s riddance pile. The first

to do so wins. As each card is played, the one beneath is turned face

up. Riddance cards may be played to one of eight piles which are

gradual y built up in the centre of the table. Each centre pile starts

with an Ace, on which is built any Two, then a Three, and so on,

until it contains thirteen cards headed by a King. Suit need not be

fol owed. When a centre pile is completed, it is turned face down

and put to one side.

Play A turn consists of one or more of the moves described below.

On your turn to play, the fol owing rules apply:

If your upcard is an Ace, you must play it to the centre to start

a pile.

If it is a Two, and an Ace is in place, you must play it to the

Ace. If it is any higher playable card, you need not play it if

there is any reason why you may prefer not to.

If you hold (in hand) an Ace or a card playable to a centre

pile, you may play it to the centre, but are not obliged to.

Playing to a centre pile entitles you to another move.

If you play of al five cards to centre piles, you draw five

more from the common stockpile and continue play.

When unable or unwil ing to play to the centre, end your turn

by making one discard face up from your hand to the table.

Any card may be discarded except an Ace. You then draw

enough cards from the top of the common stockpile to restore

your hand to five.

The first discard you make starts your first discard pile. Each

subsequent discard may be used to start a new pile, up to a

maximum of four. Alternatively, each may be added to the top of a

discard pile, provided that it is equal to or one rank lower than the

previous card. (For example, you can play a Jack or a Ten to a

previous card. (For example, you can play a Jack or a Ten to a

Jack.) You may never play to or from your opponent’s discard

piles.

To keep your turn going, you may at any time play of the top

card of a discard pile to a centre pile.

End of turn Your turn ends when you make a discard, or if you find

you can neither play to a centre pile nor make a legal discard. In

the lat er case, your hand is said to be ‘frozen’.

Frozen hands If one player’s hand is frozen, the other keeps playing

even after he has made a discard, and continues in this way until

the first player announces after a discard that he can now continue.

If both players freeze, there is a re-deal. Al the cards in play

except the riddance piles are gathered up, and shuf led and

reshuf led very thoroughly together. Deal five more each, stack the

rest face down, and start again from the beginning.

Jokers You may play a Joker to a centre pile at any time and count

it as the required card. For example, it may be cal ed an Ace and

used to start a pile, or it may be played as a Two to an Ace, a Three

to a Two, and so on. It may not, however, be played on to a King. A

Joker once played to a centre pile cannot then be removed.

Alternatively, you may play one to a discard pile, and need not

state exactly what it represents until you have to. (Thus if two

Jokers are played to a Ten, they may be fol owed by a Ten, Nine,

Eight, or Seven.) Although Aces themselves may not be discarded,

any number of Jokers may be discarded on a Two, since they can

al be counted as Twos. What a Joker stands for on top of a discard

pile does not have to be kept when it is played to a centre pile: it

can be played of as anything required.

Forced moves Most moves are optional, and if both players decline

to make any move from a given position then it is the same as if

both hands were frozen, and a re-deal is made as described above.

both hands were frozen, and a re-deal is made as described above.

There are, however, two exceptions:

1. If your upcard is an Ace, you must play it to the centre. If

there is a bare Ace in the centre, and you have a natural Two

showing as your upcard or on the top of a discard pile, then

you must play it to that Ace. (But: a Joker is not so forced

even if it logical y counts as a Two; and if you also hold a

Two you may always play it from hand instead.)

2. If both hands are frozen, or both refuse to play, the next in

turn must play an Ace or a Two from hand to the centre if he

legal y can, and his opponent must then do likewise.

End of stock When the common stockpile is reduced to twelve or

fewer cards, there is a pause while a new one is formed. This is

done by taking al the centre piles which have been built up to the

King, adding them to the existing stock, shuf ling the whole lot very

thoroughly indeed, and then laying them down as a new stockpile.

Incomplete centre piles are not taken for this purpose, unless al

are incomplete, in which case al are taken.

End of game The game ends as soon as one person has played of

the last card from his riddance pile. The winner scores a basic 5

points, plus 1 for each card left unplayed from that of the loser. Or

(my suggestion) the winner scores 1 for the first card left in the

loser’s hand, 2 for the second, 3 for the third, and so on. Thus four

left over would give the winner 10 points, five 15, and so on.

Variations The fol owing local rulesare probably commoner

thanthose described above, and must have accounted for some of

the ‘various ways of playing’ referred to by Blackwood.

The two packs are not separated but shuf led together, so each

player may have duplicates within their riddance piles. This

makes it unnecessary to deal twenty-six cards to each player’s

riddance pile, and a more popular number is twenty.