The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (12 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

Like that at all AFC posts, the social organization at Fort McKenzie conformed to a strict hierarchy. As a clerk, Malcolm Clarke found himself near the top of the post’s chain of command, below the bourgeois (technically Culbertson, though in his absence one or another high-ranking clerk) but above most everyone else, including interpreters, skilled outdoorsmen, craftsmen, and especially the

engagés

and

voyageurs

, who, quite literally, did the post’s heavy lifting. From his position in the upper 10 percent of AFC employees, Clarke could expect to negotiate with Indians, keep the post’s inventory, and take the annual returns downriver to Fort Union and beyond, sometimes as far as St. Louis. For his efforts he earned an average of about $375 per year, a little more than half of Culbertson’s annual take but close to three times what a lowly

voyageur

made.

44

I

N A SHORT BIOGRAPHY

of her father penned many years after his death, Helen Clarke acknowledged, “It would be somewhat singular if a man with as strong characteristics as Malcolm Clarke should pass through life without making enemies.”

45

By the time he arrived in Montana, Clarke had amassed quite a collection of antagonists: Lindsay Hagler and another, unnamed cadet at West Point, and, even before his troubled stay at the USMA, a boyhood classmate in Cincinnati whom Malcolm had pummeled for insulting a female classmate.

46

Clarke’s violent clash with his fellow trader Alexander Harvey was different, however, for it was born of nobler ideals than simple pride or old-fashioned chivalry. Their battle in August 1845 almost cost Malcolm his lucrative career as a fur trader just as it got underway.

Even in a profession replete with rogues and scoundrels, Alexander Harvey stood out as perhaps the most notorious individual on the Upper Missouri, a judgment rendered by contemporaries and historians alike. Though he looked the part of a “well-built storybook hero,” standing more than six feet tall and weighing in excess of 170 pounds (both impressive figures for the day), there was little about him to admire, save for his unquestioned strength and courage.

47

Born in St. Louis in 1808, Harvey in his youth found work in the saddle trade, but “as he happened to be one of those men that can never be convinced, and with whom it was no use to argue unless one wished to get into a fight,” he soon ran afoul of his employer.

48

Like other young men of that time and place, Harvey made his way upriver to fur country, arriving in the early 1830s.

Harvey worked for the AFC throughout the decade, stationed primarily at Fort McKenzie, and quickly earned a reputation as “so wicked and troublesome” (especially when drunk, which was often) that in the fall of 1839 Pierre Chouteau ordered Harvey to appear before him in St. Louis the following spring. When Harvey learned of his pending termination, he grumbled, “I will not let Mr. Chouteau wait long on me,” and set off in the dead of winter, taking only what he and his dog could carry, on the 2,300-mile overland trek to AFC headquarters. Upon his arrival in St. Louis in March 1840, the astonished Chouteau promptly reengaged him, and thus redeemed, Harvey returned to the Upper Missouri in June.

49

Chouteau’s change of heart had disastrous consequences.

During the winter of 1843–44, the AFC trader Francis Chardon turned away a Blackfoot trading party that had come to Fort McKenzie. Angered by the brusque treatment, the Indians killed a company hog as they departed. Chardon immediately dispatched some men to chastise the natives. They, in turn, ambushed their pursuers, killing a black servant, likely a slave, who belonged to Chardon. Indignant at the loss of his property, Chardon conferred with Harvey, who relished the chance to plot a reprisal. When a band of innocent and unsuspecting Piegans visited Fort McKenzie some weeks later, Harvey fired a cannon into the crowd, killing and wounding several Indians. Afterward, Harvey strode among the fallen, finishing off the dying with thrusts from his dagger. The whites celebrated their vengeance with a scalp dance that evening, forcing a handful of captured Indian women to participate in the degradation of their mutilated warriors. It took Alexander Culbertson several years to earn back the trust of the Blackfeet.

50

Under different circumstances, Malcolm Clarke and Alexander Harvey might have become allies, or at the very least evinced a grudging respect for each other, given their reputations as two of the most fearless men on the Upper Missouri. In fact, the two were bound by violence, for in 1841 they chased down and murdered a native headman of mixed Blood and Gros Ventre ancestry named Kah-ta-Nah, who had committed some infraction at Fort McKenzie. (That neither tribe retaliated afterwards suggests that the Indians may have viewed the killing as justified.)

51

Nevertheless, despite these outward similarities, they were very different men: whereas Clarke’s bellicosity was predictable, even banal—his eruptions almost always came in response to an actual or perceived slight—Harvey’s behavior was sociopathic. Clarke thus resolved to rid Montana of this threat, driven by loyalty to both Culbertson, whose bottom line Harvey endangered, and the Piegans, his wife’s people, whom Harvey had slaughtered for no cause in the so-called Fort McKenzie massacre. He waited more than a year to act.

On 16 August 1845 Harvey rode out from Fort Chardon, an AFC post on the Judith River in central Montana, to meet a passing keelboat headed upstream from Fort Union. On board were Malcolm Clarke and two veterans of the fur trade, Jacob Berger and James Lee. All three men were sworn enemies of Harvey and had plotted his murder for some time. When Harvey boarded the vessel and greeted the men, Clarke replied, “I don’t shake hands with such a damned rascal as you,” and sent him reeling with a blow from his tomahawk while Berger assaulted him with a rifle butt. Harvey recovered quickly and grabbed hold of Clarke, whom he might have killed had Lee not clouted him with a pistol. Severely wounded and thinking better of taking on three armed men, Harvey staggered off the boat and retreated to Fort Union, where he recuperated before heading off to St. Louis.

What Harvey could not settle with his fists he chose to pursue in court. Once in Missouri he thus appealed to the U.S. district attorney, and in April 1846 a grand jury indicted Berger, Clarke, and Lee on charges of attempted murder. The three men were ordered to leave Indian country immediately. Worried about losing one of their best young traders in Malcolm Clarke, the AFC quickly reassigned five key witnesses to distant parts of the Upper Missouri, placing them beyond the reach of the grand jury’s subpoena. The strategy worked, and the district attorney was forced to end the prosecution in April 1847 because of insufficient evidence against the accused.

52

Meanwhile, having survived this worrisome brush with the law, Clarke became one of the most powerful men in the AFC. In recognition of his value to the company, in the late 1840s Culbertson stationed his protégé at a new post near the mouth of the Marias River, built to replace Fort McKenzie. Situated on a broad, grassy plain on the north bank of the Missouri, Fort Benton, as it came to be called (in honor of Thomas Hart Benton, a Missouri senator and noted proponent of westward expansion), was originally built of logs, but these were replaced in the 1850s with clay dug from the riverbed, giving the structure a rare frontier permanence.

53

That Culbertson tapped Clarke for this position was no surprise, since Malcolm had excelled in his work right from the start. For instance, during the winter of 1841–42 (his first on the Upper Missouri) Clarke had helped Fort McKenzie take in a record haul of buffalo robes.

54

And Culbertson was not the only white man he impressed. Father Nicolas Point, a Jesuit priest who tried unsuccessfully to establish a permanent mission among the Blackfeet, spent eight months at various AFC posts during 1846–47. The cleric passed much of his time at Fort Lewis (a precursor to Fort Benton), where he met Clarke and even painted his portrait. Point came away deeply moved by Malcolm’s “self-sacrificing” character, which he commended to his Jesuit superiors as setting an excellent example for the “savages” while indicating also Clarke’s possible receptive ess to Catholicism. (Of that there seems to have been little chance; Clarke was baptized as an Episcopalian and, at any rate, showed only marginal interest in formal religious practice outside of the sacraments. He did, however, contribute five dollars to Point’s proposed mission.)

55

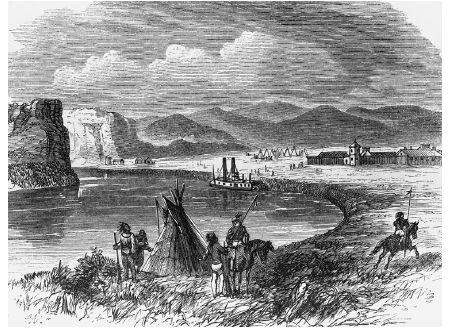

Fort Benton, ca. 1860s. Soon after its establishment in 1847, Fort Benton supplanted Fort Union as the most profitable AFC post and became the chief entrepôt and transportation hub on the Upper Missouri. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society.

Just as essential to his success as a trader was Clarke’s reputation among the Blackfeet. Although many thought him an inveterate show-off—hence the derogatory connotations of his Indian name—they admired him, too. For one thing, unlike most high-ranking AFC employees, Clarke spent considerable time, often entire winters, in their camps, where he cultivated personal relationships that facilitated trade. As a result, he earned a wide reputation among natives and whites alike for his expert knowledge of Blackfeet customs and his proficiency in their language (which he spoke along with French and Sioux).

56

Most of all, the Indians were drawn to Clarke because of his charisma. Consider the words of Calf Shirt, a Blood headman esteemed by the Blackfeet but feared and despised by most whites: “What power do you possess? Has the spirit of the Manitou fallen on you? I say to you I hate the white man, but I hate you less than any white man I ever knew.”

57

Little wonder that in due time and under Clarke’s leadership, Fort Benton supplanted Fort Union as the brightest star in the AFC firmament.

D

ESPITE HIS TREMENDOUS SUCCESS

at Fort Benton and elsewhere throughout the AFC empire, Malcolm Clarke in the spring of 1857 moved his family to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where his sister, Charlotte, was then living.

58

His reasons are unclear, but within just a few months he had become dissatisfied with “this mode of life.” He headed back to the Upper Missouri that summer with Coth-co-co-na and their children in tow. His unhappiness in the more densely settled Midwest was predictable. After all, Clarke had spent all but a few of his forty years on the nation’s frontiers and had there enjoyed the respect (if not always the affection) of Indians and whites alike.

Clarke’s decisions to return to Montana and to keep his family intact were unusual, given that many traders abandoned their Indian spouses, or “country wives,” as they were known, when they retired and returned to the United States upon their leaving the fur trade. Such was the case with James Kipp, the legendary AFC fur man, who in 1851, “after apparently wrestling with his conscience for some time,” left Earth Woman, his Mandan wife, and moved to Missouri, casting his lot with a white woman to whom he had been concurrently married and with whom he had children.

59

Not so Malcolm Clarke, who, by the admittedly low standards of the time, was an exemplary husband. That could be seen not only in his devotion to Coth-co-co-na but also in his being “one of the exceptional few who was not addicted to alcohol,” no small feat considering the abundance of liquor at trading posts and the attendant dissolution of men like Francis Chardon and Alexander Harvey.

60

Malcolm Clarke was no less committed to his four children: Helen (b. 1848), Horace (b. 1849), Nathan (b. 1852), and Isabel (b. 1861).

61

Though his work required frequent travel and though, according to Helen, he was “a stern disciplinarian,” by all accounts Clarke was an exceptionally loving parent who, like his own father, held high expectations for those who carried the family name. For this reason, Malcolm sent his two eldest children to the East for their education. Though he was able to see them only once a year, Helen recalled that such visits “flashed on us like meteors, bright, beautiful and brilliant.”

62

For her part, Coth-co-co-na was nearly undone by the separation. Years later, Horace remembered how, as the mackinaw boat carrying him and Helen slipped from its mooring at the Fort Benton levee, their bereft mother ran down the riverbank, wailing with grief, until she collapsed and could go no farther.

63