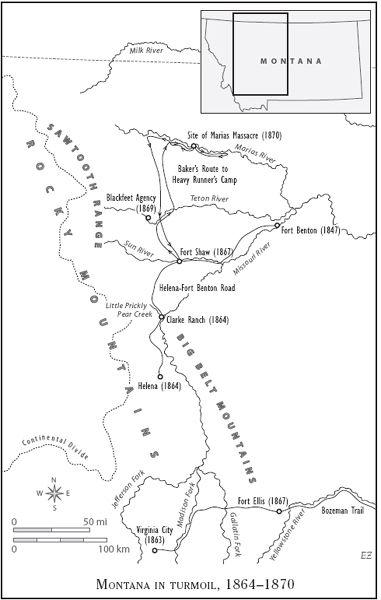

The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (16 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

Word of Clarke’s murder sent shock waves throughout Montana, and in short order the news ricocheted well beyond the territory. Nathaniel Langford, a close friend and later the first superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, wrote, “The Indians loved him, and it was a common saying among the citizens of Helena where I lived that [Malcolm Clarke] was more a friend to the Indians than to the whites, and when the news that he was killed, reached us, it was thought that a general uprising would follow.”

114

Within a few days Clarke’s sister, Charlotte, received a telegraph at her home in St. Paul. She carried the dispatch upstairs to her mother, who was visiting from Cincinnati. When she read it, the elderly woman broke down, sobbing, “[M]y bright-eyed little boy who loved his

only

mother, as he used to call me so tenderly.”

115

T

WO DAYS AFTER

the butchery, Malcolm Clarke was buried in the afternoon of 19 August 1869, on a small rise near his ranch house, mourned by numerous friends and admirers. His final resting place was a quiet and peaceful spot, described eloquently by Helen: “Afar off could be seen the rugged crags of the Bear’s Tooth, at the base of which the great river runs, and under its shadow so much of joy, so much of sorrow had met and mingled together and wrought so strange a chapter in his life.”

116

But the beauty of the grave site belied the great violence that had swirled all around it: the murder of its occupant, of course, but in a wider sense the decades of struggle between and among natives and newcomers for control of the land and its resources.

The modest cemetery had a most unexpected visitor eight years later, after the property had passed out of the Clarkes’ hands. In the summer of 1877 General William T. Sherman, whose marauding exploits in Georgia during the Civil War had earned him a reputation far more savage than Malcolm Clarke’s, made a tour of the army forts of the West. He spent much of his trip in Montana, where the Nez Perce War—the final episode in the territory’s vicious struggle between Indians and whites—was entering its climactic stage.

117

Traveling north from Helena on his visit, General Sherman stopped to rest at a quiet ranch in the Prickly Pear Valley. After a meal, he took a walk around the property, and in his wanderings he came across an unmarked grave, which he asked about when he returned to the house. Upon learning that in it lay the body of Malcolm Clarke, the general became pensive. He then explained to his host that the dead man had been a classmate of his at West Point, and that many times during the Civil War he had looked through newspapers and military reports, expecting to find mention of his old friend, probably for some gallant act. The trail had gone cold until Sherman’s chance discovery in the fastness of the Rocky Mountains.

118

Grave site of Malcolm Clarke, 2007. After a visit to his father’s grave in 1923, Clarke’s son Horace commissioned a fence to enclose it, a fitting tribute, as he put it, to “one of the greatest of Montana pioneers and a kind and good father.” Photograph by the author.

The Man Who Stands Alone with His Gun

I

f Horace Clarke’s survival was a miracle—shot in the face at close range and then left for dead—the speed of his recovery was nearly as remarkable. In the immediate aftermath of the attack on the Clarke ranch, the family retreated to the security of Helena, where Horace convalesced. But by the early autumn of 1869 he was back on the Little Prickly Pear, managing his father’s spread with his younger brother, Nathan, and living with all members of the household save for Helen, who had joined her aunt Charlotte in Minneapolis.

1

Although Horace bore no lasting effects from the shooting, he wore a thick mustache for the rest of his life, perhaps to conceal the entry wound from his assailant’s bullet.

Later that fall, rumors of an army campaign against the Piegans began circulating throughout western Montana, and in time they reached Horace’s ears. In the waning days of 1869 he traveled sixty miles to Fort Shaw to speak with Colonel Philippe Régis de Trobriand, an aristocratic French émigré and decorated Civil War veteran who oversaw military affairs in the District of Montana. Though he had no formal military experience of his own, Horace volunteered to join the expedition and offered Nathan’s services as well.

2

They intended to avenge their father’s murder, even if it meant slaughtering their own blood relatives in the process.

Officers’ quarters, Fort Shaw, 2007. It was here that Colonel Philippe Régis de Trobriand, the suave but demanding leader of U.S. military forces in Montana, resided during the planning and execution of Major Eugene M. Baker’s surprise attack on Heavy Runner’s camp. Photograph by the author.

As it happened, de Trobriand’s bête noire, Lieutenant Colonel Alfred H. Sully, was working furiously to avoid just such an outcome. Thus on New Year’s Day 1870, at almost the same moment that Horace visited Fort Shaw, Sully left the post with twenty-five enlisted men, bound for the new Blackfeet agency on the Teton River some thirty-five miles to the northwest. As the superintendent of Indian affairs for Montana Territory, Sully intended to meet with various Blackfeet chiefs about the ongoing violence against whites that enraged young men of the tribe committed. This was no simple parley, however, for Sully carried a set of imposing demands as well, including the surrender of those Piegans indicted for the murder of Malcolm Clarke and the return of hundreds of horses and mules stolen from whites throughout the preceding summer and fall.

Though skeptical about his prospects with the Indians, the lean, blue-eyed Sully was surely the right man for this delicate assignment. After all, he had extensive experience with native peoples, having served in numerous campaigns against them since the early 1840s, from Florida to California and many places in between. And that he was no racist was suggested by two of his marriages: the first to a Mexican girl he wed while stationed in California and, after her untimely death, the second to a Yankton woman he met in Dakota Territory in the 1860s.

3

Sully was known as a fair and decent man, and he traveled to the Teton River that January day animated by the dim hope of averting additional conflict between the territory’s white and Indian residents.

Whatever optimism Sully may have harbored quickly dissipated when he arrived at the agency late that afternoon. Although he had dispatched a mixed-blood scout to round up as many chiefs as possible, only four had bothered to make the trip: a Blood named Gray Eyes, and three Piegan headmen led by Heavy Runner, known to the military as a dedicated friend to the whites who favored peace. As for the other chiefs, the scout explained to Sully that he had found them too drunk to leave their camps.

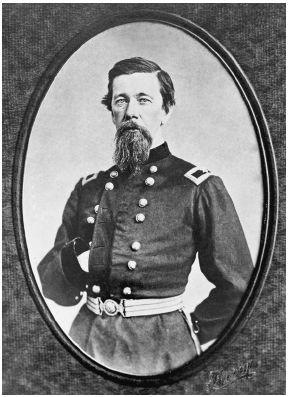

Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Sully, 1862. An accomplished artist as well as a decorated field commander, Sully sent reports from Montana in the aftermath of the Marias Massacre that earned him the enmity of Generals Phil Sheridan and William T. Sherman. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society.

In his conversations with the chiefs that night and the next morning, Sully expressed his disappointment that so few had shown up and then gave the Indians a stern speech, explaining that the U.S. government was weary of Blackfeet aggression and determined to make war on them if the natives did not cease their raiding and killing. Moreover, in an effort to convey the gravity of the situation, Sully insisted that if the army launched a military campaign against the Blackfeet, U.S. troops would pursue the Indians across the so-called Medicine Line into Canada, where native groups had long sought safe haven. Though a bluff, Sully’s threat had the desired effect, as the startled headmen promised to do all in their power to curb the depredations, return stolen livestock, and kill or capture Owl Child’s gang. Heavy Runner was so alarmed by Sully’s warning that he asked for a note of safe passage attesting to his cooperation with the whites. Sully gave the chiefs two weeks to meet his conditions.

Unbeknownst to the Indians but suspected by Horace and Nathan Clarke and other Montana whites, the gears of the U.S. war machine were already turning, and just five days after Sully’s meeting with the chiefs, Major Eugene M. Baker and four companies of the Second U.S. Cavalry moved out from Fort Ellis (near Bozeman) to Fort Shaw, to be within striking distance of Blackfeet camps if ordered to attack. When Sully’s deadline passed without the Indians’ compliance, Baker led his men into the teeth of a particularly severe Montana winter, crossing broken, snow-covered terrain in plunging temperatures. On the fourth day the troops discovered a large Piegan encampment at the Big Bend of the Marias River, and deployed quietly in a skirmish line on the bluffs overhead. Among the dozens of concerned citizens who tagged along were the two Clarke brothers.

4