The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (18 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

From the moment he arrived at Fort Shaw, Hardie understood that the situation—as he described it with characteristic understatement—had experienced substantial “modification.” But it was much more than that, a complete chiasma. In conferring with de Trobriand on 7 January, Hardie was astonished to learn that the colonel now favored a strike against the Piegans, as quickly as it could be mounted. When the inspector general asked why, after more than three months of opposing such a plan, de Trobriand had changed course so abruptly, the Frenchman cited a rash of Indian depredations in December and especially the unexpected return of Mountain Chief’s band from Canada to the U.S. side of the line, affording a prime opportunity to assail them. In order to confirm the Indians’ whereabouts, Hardie immediately dispatched Joe Kipp, the mixed-blood son of the famous trader who served as an army scout, to reconnoiter along the winding Marias River.

20

While waiting on Kipp’s report, Hardie exchanged a series of telegraph messages with Alfred Sully in Helena. If de Trobriand’s volte-face had surprised him, the inspector general was even less prepared for Sully’s change of heart. The man who throughout the summer and fall had consistently urged military action against the Piegans now counseled restraint, insisting that, although his New Year’s Day meeting with the chiefs had not yielded results, “no blood should be shed.” Instead, Sully suggested that U.S. troops attempt to kidnap Mountain Chief and half a dozen of his men, holding them hostage until the Indians produced Owl Child’s gang and the stolen livestock. Hardie was nonplussed and could only guess at the reasons behind Sully’s second thoughts.

21

Joe Kipp returned on 12 January to report that he had found various Blackfeet groups dispersed in winter camps along the Marias, with Mountain Chief’s band among them. The next day, Hardie wrote to division headquarters to offer his assessment. The inspector general was intelligent, a thorough and careful man who presented the cases made by Sully and de Trobriand with evenhandedness. But in the end he endorsed the Frenchman’s perspective, and urged Sheridan to deploy Major Eugene Baker—who was already en route to Fort Shaw with four companies of the Second U.S. Cavalry—against the Indians. Sheridan wrote back by telegraph two days later with his instructions: “If the lives and property of citizens of Montana can best be protected by striking Mountain Chief’s band of Piegans, I want them struck. Tell Baker to strike them

hard

.”

22

Sheridan’s emphasis on the final word was deliberate and offered a clear indication of what was in store.

T

HE

S

ECOND

U.S. C

AVALRY

traces its origins to May 1836, when it was established to defend the nation’s borders and facilitate westward expansion. Known until 1861 as the Second Dragoons, the regiment developed a lasting reputation for valor on the battlefield and liquor-fueled unruliness in the garrison. Though the unit earned laurels in combat against Seminoles and Mexicans during the 1840s, it secured immortality in the crucible of the Civil War. That conflict produced luminaries like General John Buford, who served as “the

beau ideal

of later generations of cavalrymen” for his heroic performance at Gettysburg, in which he seized the high ground for the Union on the battle’s first day and refused to surrender it.

23

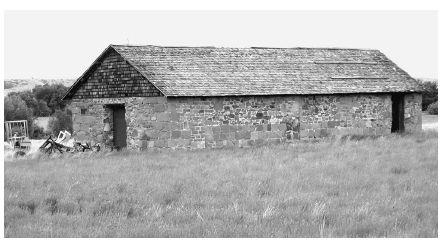

The troops of the Second Cavalry exhibited similar fortitude in the opening weeks of 1870, when the United States was engaged in a battle against another internal foe: the native peoples of the trans-Mississippi West. Few were tested quite like the detachment that marched nearly two hundred miles from Fort Ellis to Fort Shaw in eight days, arriving on 14 January. Like most of the army’s western outposts, the fort—named in honor of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw of Massachusetts, who had died leading one of the first black regiments during the Civil War—was little more than a collection of squat adobe buildings ringing a small parade ground. Given the inadequate shelter for both the men and their animals, the soldiers pitched their field tents outdoors and tried to keep warm, despite the most unforgiving winter weather seen in Montana in more than a decade. At such times troops often wore everything they had: several layers of shirts and underclothes, two pairs of pants, and an overcoat of buffalo or bearskin. Sometimes even these measures were insufficient: one contemporary observer estimated that frostbite blackened the faces and extremities of more than 10 percent of soldiers stationed on the northern Plains.

24

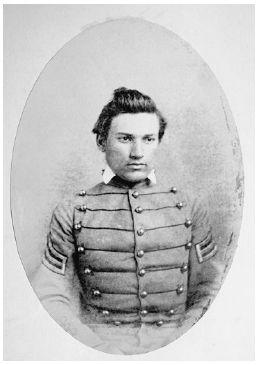

Commanding this squadron was Major Eugene M. Baker, a thirty-two-year-old native of rural upstate New York with extensive military experience in the West. Though he had muddled through the USMA without drawing much notice, Baker had developed into an accomplished officer during the Civil War. In fact, while leading a cavalry regiment during Sheridan’s ravaging of the Shenandoah Valley, he had so impressed the general that five years later Sheridan handpicked him to lead the expedition against the Piegans. Baker was equally popular with his subordinates, who marveled at his stature (tall, strong, and thickly bearded—the epitome of an American frontier soldier) and delighted in his common touch, born of a humble upbringing. However, as one member of the Second Cavalry remembered, these qualities also had a sanitizing effect, as they “did much toward bringing [the troops] into forgetfulness [of] some of the reprehensible traits of his character,” which included alcoholism and the loose exercise of authority.

25

Joining the Second Cavalry at Fort Shaw were 130 soldiers of the Thirteenth U.S. Infantry (55 mounted troops and 75 foot soldiers) as well as a few dozen civilians, none more important than the two scouts, Joe Kipp and Joe Cobell. The twenty-year-old Kipp was an obvious choice, given his earlier work at the post and especially his familiarity with both the landscape and the Blackfeet, who called him Choe Keepah. The selection of Cobell, an Italian immigrant who had come to the Upper Missouri as a fur trader in the 1850s, was more surprising, because his marriage to one of Mountain Chief’s sisters should have raised concerns about his partiality.

26

Eugene M. Baker, ca. 1859. Baker’s class photo from his time at West Point shows a young officer on the rise. The Empire State native became a personal favorite of General Phil Sheridan’s during the Civil War, but Baker’s destruction of Heavy Runner’s camp in 1870 shattered the reputations of both men and hastened Baker’s retreat into alcoholism. Courtesy of the U.S. Military Academy Archives, class album collection.

Barracks, Fort Shaw, 2007. While some members of the force that traveled to the Big Bend of the Marias bunked here in January 1870, many others had to pitch tents on the parade ground and brave the winter weather, which was brutal even by Montana’s standards. Photograph by the author.

By contrast, there was no doubting the motives of two other civilians preparing to ride out with the Second Cavalry. Having received de Trobriand’s permission to join the expedition, Horace and Nathan Clarke joined Baker and his men when the cavalry passed through the Prickly Pear Valley on its way to Fort Shaw.

27

De Trobriand probably struggled with the decision; the boys’ desire to avenge their murdered father would no doubt add an unpredictable element to the mission. Moreover, Horace—though fully recovered—was still only a few months removed from his brush with death. In the end the Frenchman may have regretted his acquiescence, as Horace rashly spilled the particulars of the campaign to a newspaper reporter; that scuttled de Trobriand’s best efforts to keep all military preparations secret, lest the Indians get warning from liquor traders eager to protect their best customers.

28

Nevertheless, by the time this story appeared in print on 21 January 1870, it proved too late to warn the Piegans. Two days earlier, Baker had taken advantage of a slight break in the weather to lead his party, swollen now to nearly four hundred men, away from Fort Shaw and on toward the Indians’ winter camps along the Marias River, seventy-five miles to the north. De Trobriand’s simple orders to Baker left much to the discretion of the commanding officer. But on one thing he (and especially his superiors in Chicago) had steadfastly insisted: the troops were not to molest in any way the friendly camps of Heavy Runner and the other Piegan chiefs who had met with Sully on New Year’s Day. Phil Sheridan was determined that this victory would be as clean as it was decisive, denying the humanitarians who had fulminated against him after the Washita battle the chance to wring their hands or shake their fists.

29

T

HE

S

UN

R

IVER

rises in the Rocky Mountains and then flows in a southeasterly course through north-central Montana, traveling 130 miles before emptying into the Missouri at the present-day city of Great Falls. The Piegans called the stream Natoe-osucti, which means “sun” or “medicine” river, the latter referring perhaps to the extraordinary purity of its cold waters. In the 1860s, as whites began to pour into the region, the Sun River provided another sort of medicine, serving as a de facto boundary between the Blackfeet and the newcomers. South of the river lay the mines and the major American settlements, Helena chief among them, but north of the stream was Indian country, stretching out 120 miles to the Canadian border.

At around ten in the morning on Thursday, 19 January 1870, Major Eugene M. Baker and his troops splashed across the icy Sun as they moved out to the north from Fort Shaw.

30

The few men remaining behind in the garrison stood at attention as the band played a musical salute, but these gestures probably did little to cheer the outbound soldiers. Though the weather had warmed a bit in the morning light, the mercury still registered a blistering thirty degrees below zero, and adding to the troopers’ discomfort, no doubt, were the unknown dangers ahead. If the U.S. military had won several victories over Plains Indian groups in recent years, it had also tasted some wrenching defeats, like the Fetterman Massacre of December 1866, in which a combined force of Arapahos, Cheyennes, and Sioux ambushed a detachment of U.S. soldiers near Fort Phil Kearny in what is now north-central Wyoming, killing all eighty of the soldiers, including twenty-seven members of Company C, Second U.S. Cavalry.

31

Baker’s column on that mid-January morning was formidable, a long procession of men, horses, and supply carts threading across the valley. To ward off the chill, the soldiers wrapped their torsos in blankets and their feet in burlap, casting them as dark figures that stood out in high relief against the pale background of the snowy terrain. Their visibility worried Baker, who wanted to preserve the element of surprise, not only for his advantage on the battlefield but also to prevent his Indian quarry from fleeing to safer realms in Canada. Baker thus settled on a strategy that, while reasonable, only added to his detachment’s misery: after the first day’s march, the column would lay up during daylight hours and push onward through the night. The soldiers made twenty miles before darkness fell on 19 January, at which point they pitched their camp in the shadow of Priest Butte, a 4,100-foot summit near the Teton River. Despite the brutal cold, the few fires that Baker allowed were kept small in order to preclude detection.

The next day was full of little else but waiting. Because the men would not move out until nightfall, they huddled for warmth in the frozen camp, tending their horses and checking their equipment while trying to ward off the strange emotional twins typical of a military campaign: anxiety and boredom. Some of the troops may have turned to the bottle for comfort, as was later claimed by one member of the company, who remembered that throughout the mission the soldiers “tried to keep their spirits up by taking spirits down.”

32

This charge—to which Baker was highly susceptible, given his widespread reputation as a drunk—would prove particularly damaging in the aftermath of the operation.