The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (22 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

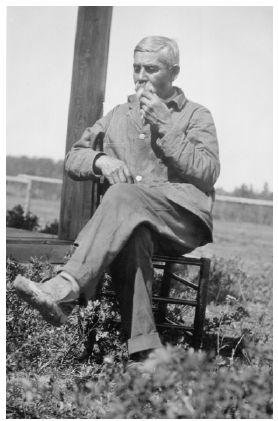

Horace Clarke, ca. 1910s. Though nearly killed the night of his father’s murder, Horace Clarke survived to avenge him at the Marias in 1870, accompanied by his younger brother, Nathan. Horace lived into his eighties and served often as a mediator between the Piegans and federal officials. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

His unsettling encounter, dreamlike as it was, provides a neat allegory for his enduring relationship to the Baker Massacre. Clarke spent most of his adult life pushing memories of the slaughter to the very margins of his conscience, hoping to downplay or even forget the details of that terrible day. This approach worked well for nearly half a century, until the ghosts of January 1870 caught up with him and forced their way into his consciousness in the twilight of his life.

J

OE

K

IPP

,

BY

contrast, would have been happy with shadowy visits from the occasional phantasm; instead, he lived forever in the harsh daylight of the massacre’s aftermath, battered by his own guilt and the Piegans’ scorn. Many Blackfeet held Kipp accountable for the deaths of their loved ones as well as for the inauguration of a desolate epoch for the Blackfeet, one marked by hunger, illness, and privation. Stunned that any foe would strike so viciously against the sick and frail in the dead of winter, Piegan chiefs abandoned all plans for retaliation within weeks of the slaughter and pressed for peace with the U.S. government through Jesuit intermediaries.

93

The shift in the natives’ fortunes were so stark thereafter that on the tenth anniversary of Baker’s campaign, a Montana writer observed, “Ever since January 1870, the Blackfeet tribes … have been peaceable and quiet, and it has been safe to travel all over their country.”

94

In other words, the carnage at the Big Bend had secured the white conquest of the northwestern Plains. And for the Piegans, Joe Kipp—more than anyone except Baker himself—became the reification of all blame for the massacre.

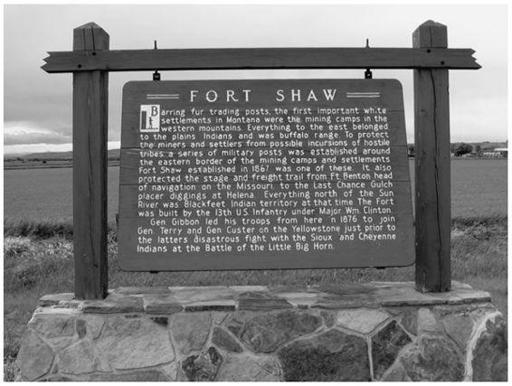

Historical marker, Fort Shaw, 2007. Although the Marias Massacre belongs in any discussion of the worst atrocities committed by American military forces against native peoples, it is largely forgotten today. Note that it does not merit even a passing mention on this placard commemorating Fort Shaw, the staging ground for the expedition against the Piegans in 1870. Photograph by the author.

Aside from his obvious responsibility in leading the troops to Heavy Runner’s camp, there were other reasons why Kipp was an easy target for Piegan frustrations. For one thing, regardless of his two decades among the Blackfeet, Kipp, in the final analysis, was not one of them: his Indian heritage was Mandan. Moreover, after 1870 he developed a reputation as one of the most successful liquor traders in the Montana–Alberta borderlands, an unsavory vocation in a place ravaged by native alcoholism and its attendant social disorders.

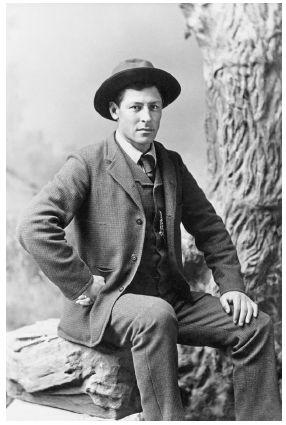

Joe Kipp, 1889. Born around 1850 to James Kipp, a prominent AFC trader, and a Mandan named Earth Woman, Kipp was one of two army scouts in Major Baker’s employ. He mistakenly led the Second U.S. Calvary to the camp of Heavy Runner, who had been guaranteed safe passage just three weeks earlier by Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Sully. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society.

In later years Kipp won over at least some of his detractors, aided no doubt by the intimate ties he developed with the Piegans. In one of the more poignant, if unusual, developments in the wake of the Marias Massacre, Kipp married Double Strike Woman (known also as Martha), one of Heavy Runner’s daughters, and then adopted several other of the slain chief’s offspring. According to a friend, Kipp doted on the children and strove to give them every advantage.

95

Nonetheless, his betrayal was so indelible that even today some on the Blackfeet Reservation who carry his name have nothing but contempt for the man. One such individual said in 1995, “I’m not about to do an Honor Dance around Joe’s grave.”

96

H

ORACE

C

LARKE FARED

much better, suffering little of the enmity that dogged Kipp. For instance, he explained to Plassmann that during the attack on Heavy Runner’s camp, one of his own uncles had fled into the river and then turned and shot at him. When Clarke explained that he had returned fire, Plassmann asked whether he had ever regretted it: “‘No,’ he replied. And I am convinced he meant what he said. Ties of blood are not considered in war time.”

97

Furthermore, as Clarke insisted, once he realized that the troops had ambushed the wrong camp that morning he tried to protect the embattled Indians, “but one could do little with soldiers after they had tasted blood.”

98

For their part, most Piegans seemed to give Clarke a pass, thinking that his participation in the slaughter was somehow justified by a desire to avenge his father’s murder. And Clarke was reasonably insulated against native skepticism by his Piegan blood and particularly his elevated social status, which derived from his father’s prominence as well as from his own entrepreneurial ventures after 1870. Whereas Kipp became a whiskey runner, dodging the law and at least once killing an obstreperous Indian customer, Clarke took a more respectable path.

99

In the mid-1870s, having sold his father’s ranch in the Prickly Pear, he moved to north-central Montana near the Highwood Mountains, where he raised cattle with his wife, Margaret, a Piegan woman known by her people as First Kill.

100

Then, in 1889, he and his family moved to the small town of Midvale, later renamed East Glacier Park, just east of the Rocky Mountains, where he acquired a homestead after the allotment of the Blackfeet Reservation. With the establishment of Glacier National Park in 1910, Clarke sold a portion of his land to the Great Northern Railway, which then erected the magnificent Glacier Park Lodge, a soaring, chalet-style resort, on Clarke’s former property, though Clarke himself did not became wealthy from this transaction.

101

To be sure, Clarke knew his own share of heartache and tragedy. Of the eight children born to him and Margaret between 1876 and 1883, four died in infancy of scarlet fever and only two—John (1881–1970) and Agnes (1883–1973)—outlived their parents. Perhaps it was the agony caused by these untimely deaths that contributed to the marital strife between him and Margaret, leading to a lengthy separation followed by divorce. Margaret remarried in the 1890s, but he did not.

102

Still, by the early years of the twentieth century, Clarke appeared to have weathered better than most mixed-bloods, and certainly all Blackfeet, the sweeping changes that had utterly transformed Montana since the buffalo days of his youth. With the influence of his sister Helen, the home they shared at East Glacier Park became a literary salon, of sorts, for those visiting the magnificent lodge next door. And it was there that the ghosts of 1870 at last caught up with him, conveyed to his doorstep, if indirectly, by Joe Kipp.

O

N

8 F

EBRUARY

1913 Kipp, aged sixty-three and in deteriorating health, gave a statement about his role in the Baker Massacre to Arthur McFatridge, Indian agent to the Blackfeet. Kipp’s description of that fratricidal attack more than four decades earlier was concise and matter-of-fact, differing from the military’s accounts on only two main points: Kipp insisted that he himself had tallied 217 dead Indians at the Big Bend (and not the 173 reported by Baker), and that afterward the U.S. soldiers had rounded up an estimated 5,000 horses (as opposed to the army figure of 300), one-tenth of which belonged to Heavy Runner alone. Kipp added that he had been only fifty or sixty yards distant from the headman when he fell, and that upon discovering Heavy Runner’s note of safe passage, the troops hurriedly buried the chief in the ground (violating the Indian custom of placing the deceased in trees), presumably to conceal the evidence.

103

While Kipp’s testimony might have been an effort to clear his conscience before he died later that year, there was also a practical reason for his statement. Joe’s adopted son Richard (usually called Dick), along with two of Richard’s half siblings, Emma Miller and William Upham (born to one of Heavy Runner’s other wives), had enlisted McFatridge to assist them in winning compensation from the federal government for the chief’s murder and the theft of his horses. And it was no small sum the Indians were after: $75,000. Why the claimants decided to act at that particular moment is unclear; perhaps Joe’s accelerating decline gave them a sense of urgency, or maybe McFatridge was more sympathetic to their cause than previous agents had been. In any event, McFatridge forwarded their inquiry to the commissioner of Indian affairs the very same day that he took Kipp’s statement.

104

After almost a year had passed with no answer from Washington, McFatridge wrote again in January 1914, and then in a third letter sent two months later he threw his own weight behind the Indians’ petition: “There is no question but that this massacre took place as was described by Joseph Kipp … and it appears to me that these people do have a just claim against the government.” He added that Dick Kipp and William Upham were contemplating a trip to the East in order to present their case in person, which surely would have caused embarrassment on Capitol Hill.

105

Whether or not the threat of a visiting Indian delegation caught the attention of federal bureaucrats, a staffer at the Department of the Interior within three weeks of receiving McFatridge’s third letter asked the War Department for all available information on Baker’s campaign and any subsequent government investigation.

106

Meanwhile, Heavy Runner’s heirs solicited and sent to Washington additional testimony from survivors of the massacre. In one deposition Bear Head described his capture by soldiers on the morning of the fight as he rounded up his horses.

107

Kills-on-the-Edge, known by whites as Mary Monroe, remembered how she and her wounded mother had fled the Big Bend and taken shelter in another Piegan camp.

108

And for good measure, the claimants also attached a statement by Alf Hamilton, a white trader, who testified to the number of Heavy Runner’s mounts in 1870, noting, “In those days an Indian would not be considered a chief unless he had several hundred head of horses.”

109

And yet it was not enough. Though the Indians won the backing of Senator Harry Lane of Oregon, who in February 1915 introduced a bill on their behalf, officials at the Interior Department refused to endorse the legislation.

110

In justifying the decision, the office of Secretary Franklin K. Lane (no relation to the senator) explained, “It is impossible to reconcile the statements of Joseph Kipp with reports which the military authorities made shortly after the events transpired,” adding that the passage of time complicated the gathering of sufficient evidence to overturn the original government version of the incident.

111

Senator Lane tried again in December with a new bill, but received precisely the same reply from the Interior Department. The plaintiffs, however, were undeterred and attempted to strengthen their hand by interviewing other Piegan eyewitnesses to the slaughter.

112

Dick Kipp even made a visit to the Big Bend in December 1916, recovering two six-shooters and posting a notice declaring that it was the site of the battle.

113

But Secretary Lane remained steadfast in his opposition to their claim, withholding his support for similar bills proposed in 1917 and 1920.