The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (17 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

The carnage that ensued on that bitter morning has been lost not only to the public but to most historians as well, eclipsed by a handful of more infamous army slaughters of Plains Indian peoples. Whereas the atrocity at Sand Creek, Colorado, in 1864 has become a byword for white brutality, and Wounded Knee in South Dakota in 1890 is notable as the last major engagement of the Indian Wars, the Marias (or Baker) Massacre, as it came to be known, soon slipped into relative obscurity, despite the immediate, if momentary, storms of protest it aroused in the East and the reforms in Indian affairs that it engendered.

5

The Piegans, however, never forgot, and neither did Horace Clarke, who lived forever in the shadows cast by the bloody events of 23 January 1870.

Itomot´ahpi Pikun´i

Though white Montanans had endured numerous Piegan assaults throughout the late 1860s, the killing of Malcolm Clarke caused unprecedented levels of anxiety and outrage in the territory. To be sure, other prominent citizens had fallen victim to ambush by the Piegans, most notably John Bozeman, a pioneer who blazed an eponymous trail to Montana Territory before his murder in 1867. And yet, according to conventional wisdom, Clarke of all people should have been safe, given his marriage to a Piegan woman and the location of his ranch so close to the perceived security of the settlement at Helena.

Newspapers throughout Montana mixed their reporting of Clarke’s death with impassioned pleas for military support. Just three days after the murder, a writer for the

New North-West

maintained, “The war cloud lowers. It is not conjecture or imagination. There is too much reality in flowing blood.” At the same time the editorialist held out little hope of imminent relief from the U.S. troops stationed in Montana. Indeed, the combined strength of the territory’s two posts—Forts Ellis and Shaw—was fewer than five hundred men. With these figures in mind, the writer lamented that “until some great massacre awakens the Government to a general retaliation under a good officer … we may expect continued and yearly recurrences of the horrors.”

6

Such alarmists found a sympathetic ear in Alfred Sully, who had arrived in Montana in May 1869 as a sort of exile. Despite valiant service in the Union army, Sully had seen his career stall in the late 1860s after he ran afoul of General Philip H. Sheridan. While serving under Sheridan on the southern Plains during the fall of 1868, Sully had clashed bitterly with Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, a Sheridan favorite. The following spring Sheridan retaliated by placing Sully on the unassigned list, a humiliation that left the forty-eight-year-old lieutenant colonel in professional limbo as a field officer without a command. In the end he was effectively banished to Montana, becoming one of many soldiers forced into civilian positions by the military drawdown after the Civil War.

7

Sully was receptive to the aggrieved Montana settlers because he was well versed in the hazards faced by white frontiersmen and their families. From his earlier postings throughout Indian country, Sully recognized the waylaid freighters, the pillaged ranchers, and especially the terrified pioneers who now implored him for assistance. Throughout the tense summer of 1869, he dutifully conveyed their apprehensions to federal officials in Washington, who in turn transmitted his communiqués to the headquarters of the U.S. Army’s Division of the Missouri (to which Montana belonged), commanded by none other than Sully’s former antagonist Phil Sheridan. While emphasizing in these messages the dangers faced by Montana whites, in advocating for military intervention Sully also adopted a classic bureaucratic pose, noting that the Indians’ livestock thefts “will make an expensive claim against the government.”

8

Not all observers shared Sully’s dire assessment, however. For instance, Alexander Culbertson, who had far greater firsthand knowledge of Montana than Sully had, argued that the recent depredations, including the murder of his friend and protégé Malcolm Clarke, were the work of “a portion of the young rabble, over whom the chiefs have no control.” Drawing on his four decades of experience with the Piegans, Culbertson blamed some of the trouble on the nonratification of recent treaties and suggested to Sully that provisioning the natives, who faced a growing subsistence crisis with the disappearance of the bison, could help calm tensions.

9

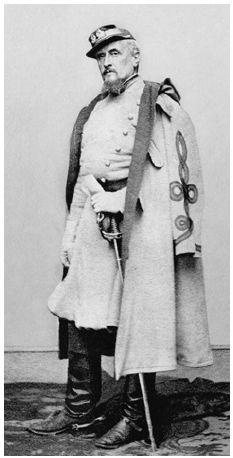

Colonel Philippe Régis de Trobriand, 1862. De Trobriand’s reputation among white Montanans soared after Baker’s slaughter on the Marias, which many residents of the territory hailed as a fitting “chastisement” for Piegan attacks on homesteads and wagon trains. Photograph in author’s collection.

More important was the opinion of Colonel de Trobriand, who, unlike Sully, placed little faith in the breathless reports of the territory’s settlers, sharing Culbertson’s belief that only a few Indians were responsible for the unrest and that they had escaped across the border to Canada, anyway.

10

Though he scorned the hysteria of Montana’s whites, he nevertheless tried to soothe their fears, as is evident in his patient reply to an October petition from Helena citizens demanding cavalry protection. With Gallic charm, de Trobriand wrote that while it was both his duty and his desire to defend all residents of Montana, “there is actually

no Indian war

in the territory.” He promised his correspondents that he would transmit their concerns to Washington, but tempered their expectations with an old French saying: “‘the prettiest girl can give but what she has.’ So with any military commander.”

11

His would not, however, be the last word on the matter.

A

S THE WINTER

of 1868–69 settled in over the southern Plains, small parties of area Indian tribes straggled into Fort Cobb in the western part of Indian Territory (now present-day Oklahoma). They were starving, and many traveled on foot because U.S. troops under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Custer had incinerated their food supplies and killed their horses. Having eaten the last of their dogs, the natives came to the army outpost seeking relief from General Sheridan, the very officer who had masterminded the devastating campaign against them. Leading one such group was Tosawi, a noted Comanche headman who had treated for peace with federal officials the year before at Medicine Lodge Creek. When he was presented to the general at Fort Cobb, the chief introduced himself by saying in broken English, “Tosawi, good Indian.”

12

Sheridan supposedly replied with a glib and chilling rejoinder that he made famous and that haunted him ever after: “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.”

13

This was the man who in the spring of 1869 became lieutenant general of the U.S. Army and assumed control of implementing military policy in the Division of the Missouri, a sweeping expanse of more than a million square miles of western territory that included the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. Sheridan’s ascent was meteoric—just eight years earlier he had been a lowly first lieutenant; now he answered only to William T. Sherman, the commanding general of the army. A powerful mix of ambition, bravery, luck, and political savvy had propelled him upward, despite his almost comical appearance. “Little Phil” stood at just five feet five inches tall, which was merely the most immediate of his physical shortcomings. Abraham Lincoln famously cataloged the others in describing the general as “a brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can skratch them without stooping.”

14

Sheridan’s fitness as a commander was beyond question, however, displayed especially in the fall of 1864 as he led his troops in laying waste to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, foreshadowing the destruction in Georgia wrought later that year by Sherman during his fabled March to the Sea.

15

Critics of Sheridan’s prosecution of the Indian Wars denounced him as a garden-variety racist, but this was an oversimplification. To be sure, he harbored the reflexive prejudice toward native peoples characteristic of his time and place, but he did not seek the Indians’ extermination. Rather, like many of the eastern reformers who loathed him, Sheridan hoped to see Indians Christianized and settled on reservations, where they could learn the skills and habits of white Americans. But he diverged from the humanitarians on the question of how to reach this goal: while the former emphasized schooling and moral suasion, Sheridan insisted that natives who raided and plundered had to feel the hard hand of war, and not merely the velvet glove.

16

It was precisely this strategy that he employed in subjugating the Indians of the southern Plains in 1868 and bringing admired men like Tosawi to their knees.

Given Sheridan’s temperament and inclination, the conflicting reports from Montana that arrived at his Chicago headquarters in the waning months of 1869 placed him in an awkward position. On the one hand, the Piegan depredations roiling the territory seemed to call for just the kind of punishment Sheridan advocated, and yet from prior experience he deeply distrusted Alfred Sully, the source of this information. On the other hand, Régis de Trobriand—whom Sherman knew and commended to Sheridan for his reliability—downplayed the violence in his district and urged restraint in pursuing the Indian offenders, advice that ran contrary to Sheridan’s naturally aggressive instincts.

In the end, Sheridan’s decision was made for him in October, as Secretary of the Interior Jacob D. Cox—on Sully’s behalf—urged the War Department to send troops against the Piegans. Responding later that month to the directives from Washington, Sheridan outlined his strategy: “I think it would be the best plan to let me find out exactly where these Indians are going to spend the winter, and about the time of a good heavy snow I will send out a party and try and strike them.”

17

Sherman endorsed the scheme two weeks later, no doubt because such tactics had worked to so-called perfection in Indian Territory the year before, giving Sheridan the signature victory of his campaign on the southern Plains. On 27 November 1868 Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, the yellow-haired boy wonder, led the Seventh U.S. Cavalry in a surprise attack against the winter camp on the Washita River of Black Kettle, a Cheyenne chief who had survived the Sand Creek Massacre four years earlier. Though Custer’s recklessness contributed to the deaths of a score of U.S. troops, the Indians suffered more than a hundred casualties, including Black Kettle and one of his wives, who were shot in the back while trying to escape.

18

The Battle of the Washita held another lesson for Sheridan: beware the public reaction. When word of Custer’s victory seeped out, harsh condemnation quickly followed from humanitarians and reformers. Though a few members of Black Kettle’s camp were no doubt responsible for some of the attacks on white settlements between the Platte River and Red River, the headman himself was known as a peace chief. Moreover, some Americans recoiled at the tactically sound but morally repugnant slaughter of the natives’ ponies and the destruction of their foodstuffs in winter, which mirrored the scorched-earth policy Sheridan had employed in the Shenandoah. Though he vigorously defended the actions of his troops, Sheridan never again trusted in the good will of an adoring but fickle public, explaining that “those very men who deafen you with their cheers today are capable tomorrow of throwing stones and mud at you.”

19

With such thoughts in mind, he proceeded cautiously in formulating his plan for Montana.

T

HOUGH MUCH IMPROVED

since the steamboat era, travel from the eastern or central United States to Montana Territory was still no easy feat in the late 1860s. For Colonel James A. Hardie, inspector general of the Division of the Missouri and a loyal Sheridan confidant, the arduous journey from Chicago to Fort Shaw took twelve days. Leaving division headquarters in Illinois on 27 December, Hardie crossed the stark and frozen Great Plains on the Union Pacific, which just eight months earlier had linked with the Central Pacific to complete the nation’s first transcontinental line. At Corinne, in Utah Territory, Hardie boarded a stagecoach for the second and much less comfortable leg of his trip, arriving at Fort Shaw (via Helena) on 7 January 1870.

Colonel Hardie was no stranger to difficult missions like this one. After all, it was he who on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg had carried orders from Washington, D.C., to western Maryland transferring command of the Army of the Potomac from Joseph Hooker to George Meade. His present assignment, however, was less straightforward. Mindful of the public backlash following the incident on the Washita, Sheridan wanted to make certain that if he sent troops into the field against the Piegans no friendly Indians would be harmed, inadvertently or otherwise. He thus dispatched Hardie to make a full report on the conditions in Montana.