The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (13 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

While interracial marriages like the one between Coth-co-co-na and Malcolm Clarke were typical on the Upper Missouri and in other pockets of the Rocky Mountain West where the fur trade still flourished in the mid-nineteenth century, most white Americans of the time condemned such relationships. To be sure, native-white unions did not spawn the same levels of anxiety and outrage as their black-white counterparts, which U.S. states from Maine to Texas prohibited by legal decree. In fact, because of the perceived utility of Indian-white intermarriage, which facilitated westward expansion and economic development, most lawmakers refused to apply such injunctions to these relationships; the one state that did, Tennessee, soon repealed it.

64

Although not illegal in the United States, native-white intermarriage hardly enjoyed widespread social acceptance. If the so-called squaw man served as the vanguard of American frontier settlement, he outlived his utility almost as soon as he had shown the proverbial flag. In the eyes of their detractors, by remaining in the wilderness and consorting with Indian peoples, such individuals reverted to a similarly primitive stage of human development, seen in their adoption of native speech, dress, customs, and beliefs. Furthermore, because many of these white men were presumed to hail from the more squalid ranks of American society (though this was not true of Malcolm Clarke), it was believed that they in turn corrupted their Indian hosts through the introduction of alcohol and the modeling of poor behavior. By this rationale, in the long run squaw men did more harm than good, for they complicated the urgent work of Christianizing and uplifting native peoples, thus retarding the process of white settlement they had initiated by coming west in the first place.

65

A more significant problem than their own supposed degeneration and their adverse effect upon Indians was the children they produced, who were known commonly as “half-breeds” (sometimes shortened scornfully to “breeds”) a term found in usage in America as early as the 1760s.

66

To many observers, mixed-blood offspring combined the very worst elements inherited from both parents: the laziness and improvidence characteristic of their lower-class white fathers, and the superstition and limited aptitude of their Indian mothers. Furthermore, peoples of mixed native-white ancestry were difficult to place within the schemes of racial classification that emerged in the nineteenth century, complicating matters surrounding property and citizenship. Most of all, the very existence of half-breeds disgusted white Americans opposed to racial amalgamation.

These prejudices found broad expression in the literature and popular culture of the day. Take, for instance, the serialization in 1849 of

The Half-Breed,

a novella by Walt Whitman. The title character is a perfidious mixed-blood named Boddo, whose physical deformities, including a hunched back, serve as an obvious criticism of Indian-white miscegenation. In the ungainly prose that characterized his earlier writings (and thus made the 1855 publication of

Leaves of Grass

so unexpected), Whitman penned this description of his protagonist: “The gazer would have been at some doubt whether to class this strange and hideous creature with the race of Red Men or White—for he was a half-breed, his mother an Indian squaw, and his father some unknown member of the race of the settlers.” As the reader learns, Boddo’s father had come west to trap and hunt and, while there, succumbed to “the hot blood of young veins” and slept with an Indian girl. Horrified by “the monstrous abortion” he sired, he becomes a monk, remaining in the West in an attempt to mitigate his son’s adverse impact on the community. Yet his vigilance comes to naught, for Boddo’s duplicity causes the death of a noble full-blooded Indian named Arrow-Tip, whose stoicism and courage reflect his unblemished racial purity.

67

So long as these mixed communities remained relatively isolated, families like the Clarkes and Culbertsons were insulated against such prejudice. But by the 1860s the sands had shifted perceptibly in places like the Upper Missouri or the Arkansas Valley in southeastern Colorado, where the brothers Charles and William Bent had established an eponymous fort in 1833 and intermarried with the Cheyennes.

68

In both locations and throughout the wider trans-Missouri West, white Americans began to appear in greater numbers in the years following the Mexican-American War, either passing through on the way to California and Oregon or settling somewhere in between. Some of these newcomers were Anglo women, whose advent in colonial settings throughout the English-speaking world usually heralded profound changes in the structures of society, with significant implications for their indigenous counterparts and racially hybrid families. For one thing, white men considered white women preferable to natives and mixed-bloods as marriage partners. For another, with their presence came a heightened attention to establishing and policing gender norms, especially where they intersected with race.

69

Historical accounts suggest that the first white woman would finally arrive on the Upper Missouri by steamboat in 1847.

70

Though Malcolm Clarke and his intermarried colleagues on the Upper Missouri could not have known it, mixed communities like theirs had not fared well in the course of American history. Time and again, gatherings of native-white families—almost always a result of fur trade interaction—had thrived along the western edges of the United States, where Anglos were scarce and the two-handed grip of civil and social authority was weak. As noted by one scholar, “Had the Americans not come, possibly a line of

metis

or halfbreeds would have existed from Oklahoma to Saskatchewan.” But come they did, and often with surprising speed.

71

It had happened in the Great Lakes region over the course of the eighteenth century, just as it did in the Lower Missouri Valley during the early decades of the nineteenth. In each instance, waves of Anglo emigrants overwhelmed these “syncretic societies” and in some cases literally erased their histories, deliberately writing such periods out of the formal accounts of the past as if Clio herself was ashamed that such debased places had ever existed.

72

Even if unaware of these depressing outcomes, some male heads of interracial families on the Upper Missouri recognized, nevertheless, the clear and present danger to their fragile world. Thus Johnny Grant, a successful rancher and himself a man of mixed ancestry, left Montana’s Deer Lodge Valley in 1867 and took his Indian wives and children to the Red River country of southeastern Manitoba.

73

Located at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers in what is now downtown Winnipeg, the community was home to thousands of mixed-blood peoples, many of whom identified themselves as a separate indigenous group called Métis.

74

A number of their American counterparts found sanctuary there, including the young mixed-blood son of Andrew Dawson, the veteran trader who in 1856 had succeeded his friend Alexander Culbertson as the AFC’s chief factor on the Upper Missouri. The boy’s guardian wrote Dawson in the spring of 1864 to encourage the trader to retire there, saying of Red River that “it is a very good place for one with an Indian family to settle.”

75

Dawson did not move to Manitoba, but neither did he stay in Montana, opting instead to return with his other mixed-blood sons (but not his Indian wife) to Scotland, the land of his birth, where he died in 1871. Dawson’s youngest son, Thomas, eventually returned to Montana, where in February 1891 he married Isabel Clarke, daughter of his father’s former partner.

76

Alone among nearly all of his contemporaries, Malcolm Clarke chose to remain on the Upper Missouri. Perhaps he thought that his corner of the Rockies was simply too remote to experience an influx of white emigrants, or at the very least he hoped that by the time of their arrival any newcomers would have adapted themselves to the mores of the frontier. Maybe he assumed that his class standing would provide sufficient insurance against the intolerance of poorer Anglo settlers. In any event, he surely entertained scant enthusiasm for leaving a place where he had enjoyed such success and lived for so long. Having spent half his fifty-two years on the Upper Missouri, he was hardly inclined to start over at Red River or, even worse, somewhere in the crowded and rapidly urbanizing East. Instead, he resolved that his family would remain in Montana, a fateful if not tragic decision that would cost him his life.

A Frontier Tragedy

The conquistador Hernán Cortés supposedly told Montezuma, ruler of the Aztec Empire in the early sixteenth century, that the Spaniards had a disease of the heart that only gold could cure.

77

Along with healthy doses of missionary and territorial zeal, this lust drove the Spanish to explore every corner of the New World. Although they found little of the precious metal in what is now the American West, nineteenth-century argonauts hit pay dirt. First came the California gold rush, which began when word of the January 1848 discovery at Sutter’s Mill leaked out. Over the next decade, more than 350,000 people flocked to the region, using pocketknives, gold pans, sluice boxes, and water cannons to coax some $550 million in gold from the California landscape.

78

The next major find was on the South Platte River in Colorado, which in the years 1859–61 drew another 100,000 migrants to the West.

79

The result was much the same in both places: a select few became rich, many more died or went home with nothing to show for their efforts, and the local Indian peoples suffered terribly from disease, exploitation, and violence. Montana’s gold rush would be no different.

Whereas gold fever spread rapidly in California and Colorado, it set in slowly in Montana.

80

In 1856 at Fort Benton, Alexander Culbertson took part in the region’s first-known commercial transaction involving gold when he skeptically accepted a bit of gold dust from a mountaineer in exchange for $1,000 worth of goods. In the end, Culbertson got the better end of the deal, for when coined the gold had a value of $1,500.

81

Trace amounts were found over the next several years, but it was an 1862 strike on Grasshopper Creek, about 150 miles southwest of Fort Benton, that set off the stampede. Within months a boomtown called Bannack had sprung up nearby and quickly counted 3,000 inhabitants. Many of the newcomers came west to escape the turmoil of the Civil War, which intensified that September with the Battle of Antietam, a fierce engagement in western Maryland that saw nearly 23,000 combined casualties. The yield from Montana’s gold mines grew steadily over the next few years, rising from $600,000 in 1862 to a peak of $18 million in 1865.

82

The transformation of Montana during the 1860s was breathtaking in speed and reach, reflected in its rapid political evolution. Montana began the decade as part of Nebraska Territory, in 1861 became a piece of the newly established Dakota Territory, and three years later achieved its own territorial status.

83

Its population soared from fewer than seven hundred white people in the area around the time of the Grasshopper Creek gold strike to almost twenty thousand by the end of the 1860s.

84

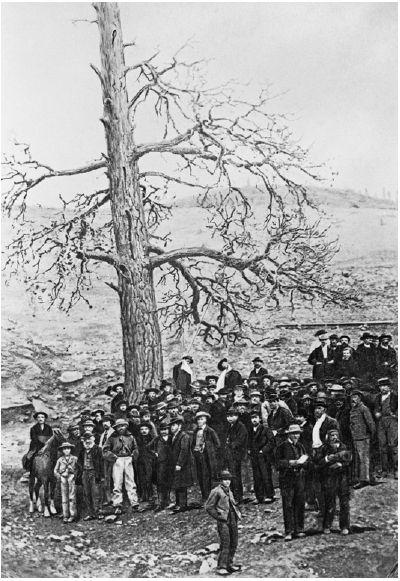

Such an influx of outsiders had enormous social ramifications, as suggested by the story of the Montana Vigilance Committee. Established in December 1863 in response to a series of robberies and murders in Montana’s gold country, the vigilantes lynched twenty-one suspected road agents over the course of six weeks in early 1864. In a clear indication of the lawlessness of the time and place, the committee’s third victim, Henry Plummer, was not only the leader of the gang but also the sheriff of Bannack.

85

Lynching tree, Helena, 1870. The rapid influx of white Americans in the 1860s led to widespread social unrest in Montana and gave rise to the infamous Vigilance Committee, which lynched more than fifty victims between 1864 and 1870. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society.

Whatever tumult gold-hungry whites might have experienced in those intoxicating days of the Montana rush was minor compared with the changing circumstances facing the approximately seven thousand Blackfeet.

86

Whereas a slow trickle of Americans bled into their country during the fur trade era, the opening years of the 1860s saw, in the words of one modern Piegan scholar, a wave that “simply overwhelmed them, much like water over a rock.”

87

Some sense of this startling transformation may be gleaned from an 1859 report by an Indian agent in Blackfeet country. That summer, the official met with several tribal elders, who, in response to the agent’s suggestion that the Indians settle down and take up farming in anticipation of rapid American settlement, politely asked him, “If the white men are so numerous, why is it the same ones who come back to the country year after year, with rarely an exception?” In his report, the agent urged authorities in Washington to invite a Blackfeet delegation to the capital so that its members might behold with their own eyes the wonders of American society. Such a visit never took place, but by 1863 it was unnecessary; the Blackfeet no longer had any doubts about the white man’s numbers and might.

88