The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (28 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

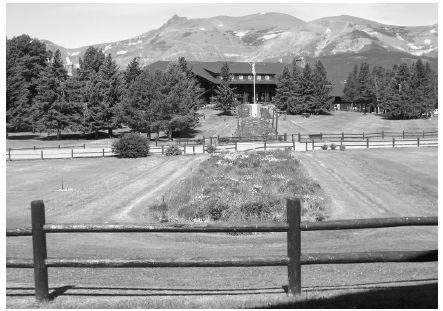

Glacier Park Lodge, 2010. Built in 1913 by the Great Northern Railway on lands that once belonged to Horace Clarke, the hotel catered to well-heeled tourists visiting Glacier National Park, which was established three years earlier. Photograph by the author.

The incompatibility of the two men’s interests was soon apparent. Whereas Grinnell hoped that the creation of the park would safeguard its natural treasures, Hill wanted to lure thousands of visitors by advertising those very same attractions. To that end, Hill adopted “See America First” as his company’s slogan, borrowing the phrase from a recent tourist promotion that sought to recapture for the U.S. market some of the $150 million spent annually by Americans traveling to Europe. Central to Hill’s vision was the construction of several Swiss-style chalets meant to evoke the Old World; that was in keeping with the growing reputation of the Glacier area as the “American Alps.” The first and grandest of these structures was the Glacier Park Lodge, which opened its doors in 1913 and stood just a few hundred yards from the railway’s Midvale station (soon renamed in honor of the park).

While early visitors to Glacier—among them Mrs. Isaac Guggenheim, Mrs. George W. Vanderbilt, and Theodore Roosevelt himself—may have marveled at the view of the Rocky Mountains from the hotel terrace, Hill was just as proud of the interior. In the lobby, guests could stock up on fancy cigars and fashionable hats, warm themselves around an open campfire, or enjoy tea service provided by a Japanese couple, all underneath a canopy of sixty-foot Douglas fir timbers that supported the soaring edifice.

86

For their part, the Piegans, some of whom Hill recruited to set up teepees nearby or perform ceremonial dances to provide a splash of local color, gave the place a simple but perfect name: Omahkoyis, meaning “Big Tree Lodge.”

H

ELEN

C

LARKE HAD

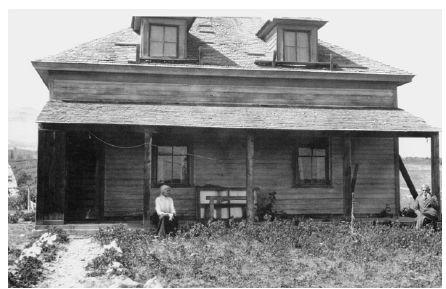

an unimpeded view of the construction work on the grand hotel, which went up directly across the road from the small frame house she had shared with her brother since 1902. Though modest, their two-story bungalow neatly encapsulated the siblings’ divergent personalities: running the length of the front was a long, covered porch, a perfect spot for the voluble Horace to smoke a pipe and regale guests with his trademark yarns; the inside, meanwhile, featured an impressive library stocked with works of fiction, drama, and sociology, where, according to one friend, Helen spent hours “communing with the gifted minds that are the glory of our literature.”

87

The defining feature of their property, however, was invisible: a boundary that marked the end of their land, which was on the extreme western edge of the Blackfeet Reservation, and the beginning of Hill’s, which sat at the eastern entrance to the park.

Helen and Horace Clarke, ca. 1910s. After her permanent return to Montana in 1902, Helen shared her brother’s small frame house at the edge of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. Their home became a regular stop for artists and intellectuals visiting Glacier country in the early twentieth century. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

Helen Clarke’s path back to Montana had been a circuitous one. Following the conclusion of her work in Indian Territory, she had passed through Midvale on the way to San Francisco, where she lived from 1900 to 1902, teaching elocution and, ever the student, learning to speak French. In California she received nearly $2,500 from the government (an indemnity for property she lost during Owl Child’s raid on her father’s ranch in 1869), but that was far less than the $20,000 she had requested, and at any rate was equal only to a year’s salary as an allotment agent.

88

For a woman nearing sixty, with neither spouse nor children to look after her in old age, combining domestic forces with her brother at Midvale—where he had lived since 1889—seemed her best bet for a secure retirement.

Even if it was not a decisive factor in her return, Clarke was also motivated by a desire to set the record straight about her supposed ostracism at the hands of the “four hundred.” Not long after she arrived from the West Coast, she sat with a journalist for an interview in which she refuted numerous details printed in that earlier story, especially those concerning her lineage. “Now, as a matter of fact,” she told the writer, “I am far from being ashamed of my origin, but on the other hand am proud of both my father and mother,” adding, “I had always numbered the very best people of Helena among my friends, and so the statement that I had been ostracised was ridiculous.”

89

Maybe so. But bypassing the capital city, where she had lived her entire adult life while in Montana, in favor of the reservation was no way to end such tongue wagging. In any event, after thirty years aloft, Piotowopaka had come home for good.

Like her sojourn in 1895–96, her arrival in 1902 came at a serendipitous moment for the Piegans. With a reservation population of approximately 2,200, the Indians were still on a slow climb back from the abyss of the starvation years nearly two decades before, and had also endured catastrophic administrative instability as Indian agents came and went, five of them between 1897 and 1900 alone. Unfortunately, the man who broke that pattern, James H. Monteath, believed that the surest way to force assimilation upon the Blackfeet was to withhold rations from anyone who, in the agent’s estimation, was able-bodied. During his ruinous tenure between 1900 and 1905, Monteath slashed the ration rolls from more than 2,000 names to fewer than 100. In terms of privation, at least, Monteath’s self-described “New Policy” must have had a very familiar feel to the Blackfeet.

90

Clarke orchestrated a campaign in the fall of 1903 to have Monteath removed, alleging “maladministration,” which included the proliferation of alcohol on the reservation. The ensuing battle was fought largely in print in two rival newspapers from Great Falls, the most sizable nearby town, as the

Daily Leader

backed the Clarke faction while the

Tribune

sided with Monteath. Through a proxy, the agent insisted that “the breeds are responsible for any dissatisfaction there may be on the reservation,” a common allegation by Indian agents who believed that peoples of mixed ancestry like Helen and Horace fomented dissension by manipulating their supposedly slow-witted relatives of pure blood.

91

On another occasion Monteath wrote the commissioner of Indian affairs to complain, “I really believe that Helen and Horace Clarke are crazy,” adding gratuitously that “their mother was insane before her death.”

92

Though the Clarkes outlasted Monteath, who was replaced in early 1905, their victory was pyrrhic: Horace spent time in the reservation jail, and Monteath blacklisted Helen with federal officials, a factor that in the opinion of an ally prevented her reappointment with the Indian Office.

93

Monteath’s vindictiveness may thus explain why, when the Blackfeet Reservation was allotted beginning in 1907, Helen Clarke was not selected for the job. Certainly she was an obvious and qualified candidate, given her extensive work in Indian Territory. Moreover, if federal authorities had once believed that her mixed ancestry gave her an advantage in dealing with native peoples, how could it be anything but a help with the Piegans, who shared her blood and trusted her counsel? Leaving nothing to chance, the Blackfeet even sent a petition signed by two hundred individuals (representing almost one-tenth of the reservation population) to the commissioner of Indian affairs recommending Clarke for the post, but to no avail; Charles Roblin, a white man who had valuable allotting experience of his own, would see the Piegans through the complex transition to a new way of life.

94

Compounding Clarke’s frustration, no doubt, was her required participation in a humiliating charade: proving her native bona fides in order to secure a homestead. Though that was a standard procedure in the allotting process, her personal history was already well known to the government. Nevertheless, on an April day in 1909, an elderly and respected chief named Little Dog shuffled into agency headquarters and testified to Roblin that Clarke’s mother was a full-blood Piegan, thus entitling her daughter to 320 acres of Montana soil.

95

Clarke must have appreciated the irony. After spending most of a decade badgering native peoples to accept allotments in Indian Territory, she had come to rely upon an Indian—and, if judged by Little Dog’s traditional dress, an unreconstructed one at that—to vouch for her native ancestry. Thus endorsed by the chief, Clarke became allottee number 283.

G

UESTS STAYING AT

New York’s brand-new McAlpin Hotel in the summer of 1913 could be forgiven if they overlooked some of the building’s state-of-the-art amenities, which included Russian and Turkish baths as well as a striking subterranean bar decorated with polychrome terra-cotta murals depicting the city’s maritime history.

96

Instead, their attention would have been drawn to the rooftop of the building, located at the intersection of Broadway and Thirty-Fourth Street, where a group of visiting Blackfeet Indians had pitched their teepees, because—in the words of their chief, Three Bear—“my people want air … [a] hot room [is] no good. [We] want plenty [of time] outdoors.” Louis Hill had brought the natives to New York to promote Glacier National Park, and before they left, the Blackfeet took in sights like the Brooklyn Bridge, the Bronx Zoo, and that quintessential feature of modern city life, the new subway system, then in its infancy.

97

Hill’s publicity stunt had the desired effect, as Helen and Horace Clarke watched scores of well-dressed easterners disembark from the Great Northern’s Oriental Limited during the hotel’s inaugural season. These visitors then spent vast sums of money at the lodge or on a variety of recreational activities, from hunting and fishing to touring the park’s backcountry on horseback with an expert guide. As the air turned chilly and the leaves began to fall, bringing the curtain down on the lodge’s spectacular debut season, the Clarkes could see clearly that Glacier National Park offered economic opportunity for them as well.

In truth, they needed extra income. If in their twilight years both enjoyed good health, their finances were not nearly so robust. Like many mixed-blood people on the reservation, who by this time constituted nearly half its total population, the Clarkes ran a few cattle and grew hay. Such ventures, however, were becoming increasingly difficult to sustain, as the allotment process continued to carve up tribal lands and thus reduce common grazing space.

98

More to the point is a recollection by one of Helen’s friends: “Neither of them had much business ability so they never made much money.”

99

Some sense of the Clarkes’ economic hardships emerges in a series of letters between Helen and J. H. Sherburne, who was the licensed Indian trader on the Blackfeet Reservation. Born in Maine in 1851, Sherburne as a young man had migrated west in search of work and wound up eventually in Indian Territory, where in 1876 he started a trading post. There he met Helen Clarke and was so inspired by her “stories of the great west, and especially Montana … [that] we turned our thoughts to the big open spaces in the land of the great mountains.”

100

In the end, her encouragement of Sherburne served as a Trojan horse of sorts; according to one observer, by the early 1920s the trader had devoured huge portions of the reservation by buying up the land patents of impoverished Indians.

101

Although Helen and her brother were not as destitute as many of their neighbors, her correspondence with Sherburne indicates that they were nevertheless on intimate terms with privation. For instance, in one letter she requested a package of rat poison, as “my house is alive with mice.” In another, scribbled during a brutal cold snap, Helen asked about a shipment of goods that had not yet arrived. Noting that she had only enough heating oil to get her through the night, she wrote, “We are in a sad plight—no oil … and soon no butter … send goods so soon as you can.”

102

These missives, however, were probably easier to draft than the many concluding with apologies like this one, from January 1916: “Wish we could have paid more on old note—but a little is better than nothing.”

103