The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (31 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

From the beginning the NDSD was a family operation. Spear’s deaf wife, Julia, a handsome woman with sandy hair worn in a bun, served as the school’s matron, handling all the cooking and cleaning and assuming her husband’s administrative duties when illness incapacitated him. Julia’s younger sister, Clara Halvorson, who could hear, accepted an appointment as the NDSD’s first teacher. And the Spears had a dog, an enormous Saint Bernard named Kent who, true to the popular image of the breed, loved to frolic in the snow, a trait that forever endeared him to the children.

This welcoming atmosphere eased the inevitable homesickness and anxiety that students experienced, which must have been particularly acute for John Clarke when he arrived just before Thanksgiving in 1894. After all, the boy was much farther from home than most of his fifty-odd classmates and stood out as perhaps the only one among them with native ancestry. Maybe the Christmas party that year, described lovingly in the school newspaper, lifted his spirits: “The pupils’ dialogues were done in sign language. The Christmas tree was prettily decorated with colored candles. … Promptly at 7:30 P.M. Santa Claus rapped on the window. What followed can only be imagined.”

John soon learned that while such merriment had its place at the NDSD, it was secondary to the academic aims promoted by Anson Spear. Photos of the bespectacled superintendent suggest that he was aptly named—thin and sharp, with dark, piercing eyes. And he was utterly devoted to his work. Central to Spear’s educational vision was his belief in manualism, which placed him on one side of a contentious and enduring debate. Advocates of this approach favored the teaching of American Sign Language (ASL), which was thought to unite the deaf by a common means of communication and, by extension, a similar set of cultural experiences.

12

After the Civil War, however, another instructional method gained momentum, one that emphasized lipreading and the acquisition of speech. These oralists insisted that deafness was a handicap to be overcome on the road to inclusion in mainstream society, and that reliance upon hand signs imposed unnecessary and humiliating segregation on the deaf. Especially with the establishment in 1867 of the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts, proponents of oralism made significant inroads in American deaf education, and by century’s end they had achieved rough parity with the manualists.

13

Spear, however, remained doggedly committed to manualism and the larger goal of building a national deaf community. To that end, he incorporated vocational instruction into the NDSD curriculum, so that graduates emerged with self-reliance and a firm set of job skills, insulating them against potential prejudice from the hearing. Thus, in addition to instruction in basic subjects like reading, writing, and mathematics, girls learned sewing and needlework while boys like John trained as printers on a small, foot-powered press.

The two and a half years John Clarke spent at the NDSD had profound implications for the rest of his life. For one thing, Spear’s devotion to manualism meant that John never learned to lip-read, a fact that in later years surprised some of the visitors to his art studio. On the other hand, John became fluent in ASL during his time in North Dakota, which he augmented with Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), a centuries-old form of communication that developed among the many Great Plains tribes, which shared no mutual spoken tongue (ASL and PISL are lexically similar but linguistically unrelated).

14

John’s time in North Dakota helped, too, in the acquisition of the skills he needed to communicate with those inexpert in signed communication. Shortly after his arrival in the fall of 1894, John composed the first missive he ever sent, which contained the letters of the alphabet, a handful of words he had learned, and the transcription of a sentence. His father was deeply moved, and wrote in reply, “My Dear, Dear Son, How thankful I am that a kind Providence has provided you the means to make known your thoughts. I trust that by spring you will be able to write understandingly and intelligently. This letter of yours being the first, I will cherish and keep always.”

15

As important as the development of literacy and communication skills was the hardy work ethic that Spear preached and modeled and that took root in John. In his adulthood, Clarke treated woodcarving as a vocation, laboring at it almost every day and using his skills to support himself and his family, precisely the self-reliance that Spear had envisioned. Clarke was so dedicated to his craft that he packed carving tools among his personal effects when he entered the hospital for what turned out to be the last time. And yet a life of such purpose and creativity was scarcely imaginable in June 1897 when he left Devil’s Lake for home and an uncertain future.

A

RECURRING THEME

in the legend of John L. Clarke is that he was discovered sometime before World War I by Louis W. Hill, the president of the Great Northern Railway. According to a contemporary newspaper article, after a guided hike through the backcountry of Glacier National Park, Hill noticed his Indian escort intently sketching a lovely panorama of Glacier’s Two Medicine Falls using a lead pencil and a piece of rough board. When Hill asked the young man what he was drawing, Clarke communicated that he was “just putting down what Great Spirit heap up hisself.”

16

The railroad magnate was sufficiently impressed that, upon returning to his home in St. Paul, he shipped some proper materials to Clarke so that the prodigy might execute the scene in oil. Shortly after Christmas, Hill opened a package from Montana and “was suddenly taken back to ‘God’s Own Country,’ as he expressed it … clothed in all the radiance of its gorgeous, natural garb.” The tableau enjoyed prominent display in the family mansion for years thereafter.

Central to this account is the notion that Clarke “was a born artist and came into the light of things artistic with nature as his only teacher.” A catalog for one of his art exhibits many years later was even more explicit in making this point: “Nearly full blooded, [Clarke] takes the natural Indian’s delight in hunting and fishing and to this he adapted his early carving in wood.”

17

Though it conjures up the hoary stereotype of the “ecological Indian” who lives in perfect harmony with his surroundings, there was at least some truth in this telling.

18

As Clarke himself explained much later, he began experimenting with forms at a tender age: “When I was a boy I first used mud that was solid or sticky enough from any place I could find it,” including the riverbanks near his home.

19

Even if John showed creative promise early in his youth, it is inaccurate to suggest that he was entirely self-taught, a claim that others, including his wife, made occasionally but that he himself never did. As it happened, two brief yet critical interventions around the turn of the twentieth century harnessed his abilities and propelled him into a career as a woodcut artist. The first of these took place just after Christmas 1898, when John left his father’s home at Midvale, where he had lived since returning from the NDSD eighteen months before, and traveled two hundred miles south to the small town of Boulder, Montana.

Established in the early 1860s as a stagecoach stop between Fort Benton and the goldfields of the territory’s southwestern corner, Boulder took its name from the huge rocks cluttering the small valley where it nestled. The settlement rose to local prominence in the 1880s, thanks to some nearby hot springs and especially its designation as the seat of Jefferson County. The town fathers capitalized on this momentum to lure a range of state institutions during the early years of the next decade, among them the Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum.

Located originally in a rented home, the school upgraded to an extraordinary new facility on the town’s east side just months before John Clarke’s matriculation. Fashioned from vermillion-colored bricks and combining the Italianate and Renaissance Revival styles that were popular at the time, the structure boasted a gabled roof, cantilevered granite stairways, maple floors, a glazed tile fireplace, and other flourishes. One reporter who happened to be deaf and “semi-mute” himself wrote, “Anyone taking the time to visit this school will go away with the feeling that this is a mighty good world to live in, especially the section called Montana, since she treats her unfortunates in such a splendid manner.”

20

For the eighteen-year-old Clarke, it was not the majesty of the schoolhouse but what took place inside that made all the difference. He recalled, “While I attended the Boulder School for the Deaf, there was a carving class. This was my first experience in carving. … I carve because I take great pleasure in making what I see that is beautiful.”

21

Though the course was probably vocational in nature, Clarke was less interested in making decorative plaques and other items manufactured in shop classes of the period.

22

Rather, as he explained, “When I see an animal I feel the wish to create it in wood as near as possible.”

Though a pivotal interlude in his artistic development, his stay in Boulder was nevertheless a short one: nine months later he was back at his father’s Midvale home in time to be counted in the September 1899 census on the Blackfeet Reservation. Such brevity suggests that Clarke may have attended the Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum specifically to take the carving class he so enjoyed. In any event, he did not tarry long with his family, leaving at some point that autumn for one last round of schooling, this time in St. Francis, Wisconsin, just outside of Milwaukee.

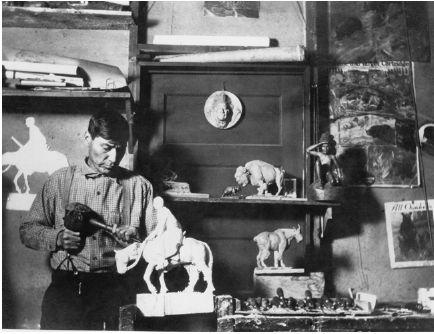

John L. Clarke in his studio, 1920s. Described by one visitor as a “scene from the animal kingdom,” Clarke’s studio at East Glacier Park was crowded with carvings in various stages of completion. Note the Rocky Mountain goat, his signature subject, at the center. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

Like those of his enrollment at the NDSD, the moment and especially the choice of location invite scrutiny. And once again it seems that Clarke family dynamics were involved, with Aunt Helen playing perhaps a decisive role. Certainly the two crossed paths in Midvale in the summer of 1899, as Helen had returned from her allotment work in Indian Territory just as John, then eighteen, concluded his studies in Boulder. It is easy to imagine the boy’s aunt, a former teacher, encouraging her nephew to continue his education and, given her devout Catholicism, suggesting a parochial institution despite its location fifteen hundred miles to the east.

If indeed the appeal of religious instruction was a key variable in the decision to send John to Wisconsin, Helen, or whoever urged such an outcome, could hardly have chosen a better environment for the teenager. The village of St. Francis owed its existence to the Catholic church, for it was founded in 1849 by eleven Franciscan laypeople from Bavaria who had immigrated, at the behest of Milwaukee’s first archbishop, to minister to the city’s growing German population. Seven years later the group built a seminary on the shores of Lake Michigan, cementing the importance of the little town in the religious life of the greater Milwaukee area.

St. John’s School for the Deaf opened in the late nineteenth century about a mile inland from the seminary complex and soon became the hub of Milwaukee’s small but cohesive deaf community.

23

Though archdiocese records indicate that Clarke enrolled on 4 November 1899, no record of his initial impression survives. But Milwaukee must have impressed him: with nearly 300,000 residents it was the fourteenth-largest city in the United States, and easily the most imposing urban agglomeration he had ever seen. While he could not distinguish their unusual accents, he surely registered the diversity of the city’s many immigrant groups in other ways: the colorful ethnic dress of various eastern European peoples; austere Scandinavians, their faces toughened by years of hard farm labor; and the unintelligible signs adorning German breweries, leather shops, and grocery stores.

24

The school’s director recognized his new student’s creative abilities right away. “John had great talent for drawing,” he remembered, “and was the most wonderful penman.” Still, he wanted him, like all his charges, to develop a marketable skill, and thus he pushed woodworking instead. The director also emphasized the spiritual component of Clarke’s education, noting proudly that during Clarke’s time at St. John’s, he “acquire[d] a good religious training and firmer character.”

25

While the director considered these two pursuits of equal importance, his student apparently did not: John carved for the rest of his life, but evinced little interest in organized religion.

26