The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (33 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

Jutting out at a ninety-degree angle on the new building’s south side (the side closest to the Glacier Park Lodge, situated just down the road) was a cantilevered sign reading “Indian Sculptor.” Clarke also changed the lettering on the placard hanging over the front door. Whereas in the old location the board had read “John L. Clarke” on the top with “art carvings, paintings, and Indian curios” written underneath, he made a slight but intriguing amendment in its new iteration, adding “Navajo Goods” to the lower left-hand corner, below his name.

This was a peculiar bit of advertising, not least because the Navajo Reservation was more than one thousand miles away in the Four Corners area of the American Southwest, which Clarke had never visited. And it is doubtful that he had many, if any, Navajo items on hand. Rather, such marketing tied Clarke directly to the “Indian craze” of the early twentieth century, a moment characterized by the fetishizing of native cultures, especially their handicrafts, by members of the white elite and middle class. These consumers treasured Indian artwork for its perceived “realness” and simplicity, exactly the qualities such people found lacking in the increasingly complex world of urban America. Because of their enormously popular textiles and silver jewelry, “Navajo” became synonymous with “Indian-made,” precisely the message Clarke hoped to convey to passersby with his new billboard, even if he was Piegan.

42

His work from this period appealed to the antimodern aesthetic then in vogue, in form if not necessarily in theme. In the late teens and throughout the twenties, he carved almost exclusively figures of animals encountered in Glacier National Park, often using his favorite medium, cottonwood, which he preferred for its relative softness. If not explicitly “Indian” in terms of their motifs, the lifelike attributes with which Clarke endowed these creations seemed to suggest his distinctive ability, as a person of native ancestry, to commune with such creatures. One reviewer observed in 1926, “[His] cottonwood bears and deer … seem to live and have personality. Many a carver has given us realistic textures, but only occasionally does one underlay them with such knowledge of his subject and such life.”

43

What Clarke thought about this sort of essentialism remains a mystery, although if it helped sell his carvings, so much the better.

O

NE OF THE MOST PROMINENT

Americans swept up in the Indian craze of the early twentieth century was John D. Rockefeller Jr., the only son of the Standard Oil tycoon. Junior, as he was known (in order to distinguish him from his father), and his family made four trips to the West between 1920 and 1930, traveling in their own private railcar, valued at $125,000 and costing $50,000 a year to maintain, as well as by automobile and on horseback.

44

On these sojourns Rockefeller and his wife, Abby, became avid collectors of Indian art, and in time their collection boasted pieces by a variety of indigenous peoples, among them the Apaches, the Nez Perces, and the Sioux, not to mention the obligatory Navajo blankets and silver jewelry.

If each of the trips had its special marvels—Mesa Verde, Yellowstone, Grand Teton—Rockefeller’s son David insisted that the family’s 1924 trip to Glacier National Park stood out in their collective memory because of the time they spent at a Blackfeet encampment. The group loved the painted teepees, and Junior, though nearly fifty, expressed childish delight when a tribal leader bestowed upon him an honorary Indian name, Imata-Koan (Little Dog). After two weeks spent camping and riding in the rolling countryside east of the park, members of the Rockefeller party retired to the more comfortable accommodations of the Glacier Park Lodge, where they were surprised to find many of the same Indians they had met in the field now providing “local color” for the arriving guests.

45

Sometime during his stay at the lodge, Rockefeller wandered up the road to John Clarke’s studio to have a look. To the young mogul, it was quite a sight. Sitting on the front porch were carvings of a bighorn sheep and a Rocky Mountain goat large enough to serve as visitor seating. It was the inside, however—described years later by one newspaper reporter as “a scene from the animal kingdom”—that really impressed, with its cluttered array of carving tools and works in progress. On the occasion of Rockefeller’s visit, Clarke may have hung back at first, as he usually took the measure of his guests’ interest—if they seemed truly curious, he would then eagerly show them the best pieces.

46

Junior did not disappoint that summer day; he purchased eight items, including a standing grizzly bear nearly three feet tall, as well as one of the finest carvings Clarke ever executed,

Fighting Buffaloes

, a cottonwood sculpture measuring 11 × 19 × 11 inches that depicts two bison bulls locked in the type of head-to-head combat typical during mating season. Crafted with hammer and chisel, the sculpture exudes an almost tangible power, seen in the animals’ twisted bodies and straining legs. The features were so impressive that they led one critic to liken the piece to the

Laocoön Group

from ancient Greece, in which three human figures writhe in agony from strangulation by sea serpents.

47

Today the carving is a prized part of the David and Peggy Rockefeller Collection, where it resides along with masterpieces by luminaries like Manet, Picasso, and Renoir.

48

If it was a thrill for Clarke to sell pieces to such a famous collector, Rockefeller’s purchases marked merely one of Clarke’s many triumphs during the 1920s and 1930s. For instance, in 1922 he earned $275, to that point his highest commission for a single piece, from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for

Bear in a Trap

. Six years later he won a silver medal from the Spokane Art Association. And in 1932, at a time when Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist German Workers’ Party were waiting in the wings to seize power, a group of sculptors from the village of Oberammergau, a world-renowned woodcarving center in Bavaria, spent part of the summer studying with Clarke at East Glacier Park.

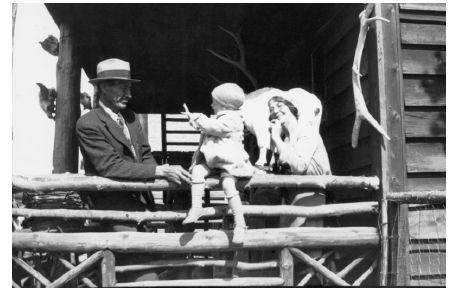

Clarke’s personal life continued to trump any professional successes. In 1931 he and Mamie traveled to Helena to adopt a two-year-old white girl, whom they named Joyce Marie. Pleased as John was, Mamie might have been even more elated, because she had lost a child during her brief first marriage, and at fifty despaired of ever becoming a mother. Joyce remembers her father as an especially doting parent, which photographs from her youth also suggest. Though he rarely smiled for pictures, many of the images of father and daughter show John beaming, the most touching of which captures the two holding cherished objects: a carved deer in his hand, a rag doll in hers. Like her mother, Joyce became a skilled communicator in sign language.

John and Joyce Clarke, ca. 1930s. Like her mother, Joyce—who was adopted at the age of two—could communicate easily with John in sign language. Here the two pose with treasured objects. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

Despite John’s domestic contentment and artistic accomplishments, times were hardly flush at the Clarke household. Big paydays like the commission from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts or the windfall from the Rockefeller visit were rare; indeed, the economic climate of the time was dire, affecting artists of the 1930s quite profoundly, and he got by mostly selling smaller pieces one at a time. Years later a friend recalled his first encounter with Clarke, during the Christmas season of 1943. That winter John set up a card table in a Helena department store, where he whittled on site and peddled small pieces for “dirt cheap” prices: one dollar for tiny figurines; fifteen to twenty dollars for exquisite six-inch mountain goats and bears.

49

Joyce explained, “Looking back … we were poor, but I didn’t realize it,” in part because she could ride horses every day.

50

Still, as a little girl Joyce treasured visits from a wealthy family friend who lived in Tacoma, because on those occasions she got to dine at the Glacier Park Lodge, an extravagance her parents could never afford.

51

The challenges facing the Clarkes during the 1930s are underscored in a series of letters between Mamie and Eleanor Sherman, the great-granddaughter of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, founder of the American School for the Deaf as well as the namesake of the national college for the deaf and hard of hearing in Washington, D.C. Sherman was the curator of the Hispanic Society of America in New York, but as a deaf person herself, she did extensive volunteer work within the deaf community.

52

In this capacity she wrote to John in June 1934 with an invitation to participate in that summer’s International Exhibition of Fine and Applied Arts by Deaf Artists, which she was helping to organize. In her pitch to him, Sherman made a nationalist appeal, informed perhaps by the growing tensions on the other side of the Atlantic: “Europe is sending works of art by 53 artists. … We Americans can sustain the high standard only through the exhibition of paintings, engravings, and carvings by acknowledged leaders such as yourself.”

53

Mamie wrote back immediately to confirm John’s interest, thus initiating a relationship with Sherman that lasted into the next decade. Mamie explained that she would arrange for a number of her husband’s pieces to be shipped from Chicago, where they were on loan to another museum. And while she expressed delight that John’s work would show alongside the likes of the celebrated etcher Cadwallader Washburn, it was neither fame nor patriotism that held the greatest appeal. Rather, as she observed in a later note, “I am so anxious to sell something; we need money, & that is why I priced [the pieces] so very low.”

54

Though some forty items sold during the three-week exhibition, John’s works were not among them. Ever resourceful, Mamie asked that Sherman keep John’s entries on hand in New York, in the hope that Sherman might find a display space or even a gallery to exhibit them. In an act of great kindness, Sherman agreed and spent much of the next seven years serving the Clarkes informally as John’s agent. Understanding their perilous financial situation, she refused to accept any commission, which could amount to over 50 percent of the sale price. Mamie, however, insisted that Sherman take 20 percent.

John, Joyce, and Mamie Clarke, ca. 1930s. While John achieved professional renown (if not financial security) in the 1920s and 1930s, he found even greater satisfaction in his home life. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

Sherman worked doggedly on the Clarkes’ behalf, exploring multiple sales opportunities, including the submission of a bear carving as a raffle prize and the installation of some pieces in a display at the Abercrombie and Fitch flagship store, then at Madison Avenue and Forty-Fifth Street in Manhattan. The return on her efforts was negligible, however. That led to plaintive letters from Mamie stressing the family’s indigence. Consider this typical missive from July 1939: “We need money at present very much. … I’ve been ill

all

spring & summer.”

55

In order to augment his meager income, John offered a carving class at Browning High School during the 1936–37 school year, and starting in the 1940s he, Mamie, and Joyce spent several winters in Great Falls, where John taught at the Montana School for the Deaf and Dumb, which, with a slightly amended name, had relocated from Boulder in 1937.

Sherman’s relationship with the Clarkes ended amicably but abruptly during the winter of 1940–41, for reasons that are unclear. Perhaps she became too busy at the Hispanic Society or wanted to focus on her recent marriage to Juan Font, a Puerto Rican who served as the art director at various Spanish-language publications. In any event, the rupture surely disappointed John and especially Mamie, who fretted even more about money as her health began to deteriorate. Though praise for John’s work was abundant, sales were poor, a contradiction in terms that Charlie Russell observed in his letter to John in 1918: “Your worke is like mine maney people like to look at it but there are few buyers.” John could only take cold comfort from that message; admiration was nice, but financial stability was better yet.