The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (35 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

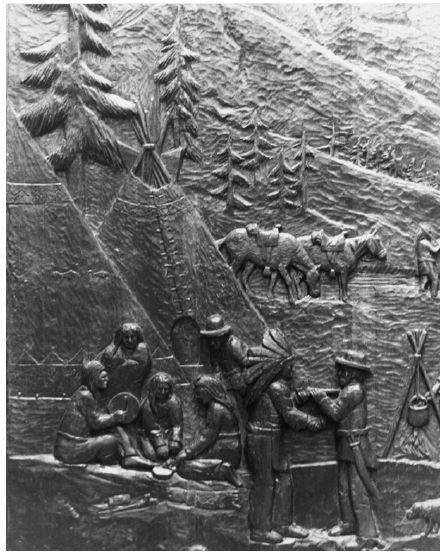

Completing this narrative arc was a panel on the right side of the entryway portraying what, as it turned out, marked the beginning of the end for the Piegans’ traditional lifeways. The frieze shows an Indian encampment—clearly a favorite subject for Clarke—in the Rocky Mountain foothills, with a stand of teepees in the foreground and some grazing horses in the distance. Clarke draws the viewers’ eyes to the center-bottom, where two Americans have arrived at the camp. One of the men peers over the shoulders of four Indian women who are preparing a meal, while the other—identified as a soldier by the sword dangling from his belt—accepts what looks to be a pipe from a Piegan warrior bedecked in a flowing headdress. The scene is friendly enough, absent any hint of the future violence that resulted from the collision of these two disparate cultures.

Resplendent as they were to the casual viewer, the panels did not exactly enrich the Clarkes. As Mamie put it ruefully in a letter to Eleanor Sherman, “They [the friezes] are grand … but he received only a pittance for the job.”

72

It seems doubtful, however, that John was too disappointed. After all, the commission was a prestigious one, and given the widespread hardships of the Depression, some income was better than none.

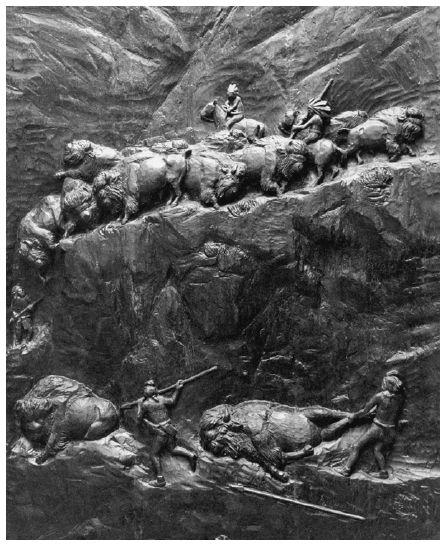

John L. Clarke, frieze for the Blackfeet Community Hospital, ca. 1940. This frieze, one of Clarke’s finest, depicts Piegans slaughtering bison in the old way—by running them over a cliff and then piercing the wounded creatures with arrows and spears. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

Sadly, not everyone on the reservation held the pieces in such high regard. After several incidents of vandalism, hospital staff removed the friezes around 1965, at which point they were warehoused at an off-site location. Years later, Clarke’s former student Albert Racine lovingly restored the pieces and returned them to the Blackfeet Community Hospital in 1986 on the occasion of the facility’s grand reopening after a nearly two-decade (and $9.2 million) effort to improve healthcare on the reservation. At that time the two vertical panels were installed in the hospital’s waiting room (though with the sequencing reversed), with the horizontal frieze placed above the receptionist’s desk in the main office.

73

C

LARKE HAD SCARCELY

put the last touches on his friezes for the Blackfeet Community Hospital when he secured another commission for a federal project. In the late 1930s the Works Progress Administration sponsored the construction of two tribally run native arts facilities that would showcase indigenous artifacts and promote craft cooperatives for local artists. First to open was the Sioux Indian Museum in Rapid City, South Dakota, followed shortly by the Museum of the Plains Indian at Browning, Montana, on the Blackfeet Reservation. A third facility, focused on the southern Plains, was established nearly a decade later at Anadarko, Oklahoma.

74

These institutions owed their existence to the work of people like John Collier, who strove to reorient government policy from forced acculturation to cultural self-determination. The embers of such efforts survived the repressive measures of the Termination Era and caught fire in the 1960s.

75

For the Museum of the Plains Indian, Clarke executed two five- by three-foot wood relief panels, once again in lauan and capturing scenes from the bygone buffalo days. Placed above the two entry-ways leading into the building, the frieze on the left depicts a group of three Blackfeet men gesturing toward a herd of bison just visible in the distance. Above the opposite door is a domestic counterpart to the hunting party: a mounted warrior in headdress riding into camp trailed by his wife, also on horseback and pulling a travois, as well as the family dog, all looking fatigued from their voyage but heartened by the sight of the teepees up ahead.

John L. Clarke, frieze for the Blackfeet Community Hospital, ca. 1940. Paired with the other frieze (page 230), this carving hints at the transformations wrought in the Piegan world by the arrival of white outsiders. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

While the panels were his most public contributions to the museum, Clarke executed a second project there in the autumn of 1941 that had a different significance. At the close of the tourist season that year, he regularly made the twenty-mile trip between East Glacier and Browning, where he created a series of plaster casts demonstrating the successive steps by which Blackfeet women prepared bison hides in the nineteenth century and before. Each between twelve and eighteen inches high, the monochrome molds showed native women at their labors, whether tanning skins by applying a mixture of brains, liver, and grease or softening the hides by pulling them through a hole in the shoulder blade or against a rope fashioned from animal sinew.

76

Perhaps Clarke was struck by the circularity of his endeavor; a century earlier, his grandmother Coth-co-no-na employed those same time-honored techniques, transforming scores of animal carcasses into goods for use or commodities for exchange.

Clarke’s plaster molds were the idea of John C. Ewers, the founding director of the Museum of the Plains Indian. On a superficial level, the two men made an unlikely pair, as Ewers—who was white and more than two decades Clarke’s junior—hailed from Cleveland and had studied at Dartmouth College before enrolling in Yale’s graduate program in anthropology, where he worked with the famed ethnographer Clark Wissler. After completing his master’s degree, Ewers left New Haven to take a curatorial job with the National Park Service, stationed first at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and then in California at Yosemite National Park. Early in 1941 he and his family moved to northwestern Montana, where in time Ewers would become the world’s foremost non-native authority on the Blackfeet.

77

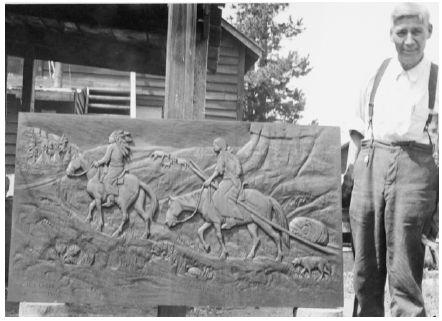

John L. Clarke, frieze for the Museum of the Plains Indian, ca. 1940s. Besides wildlife, among Clarke’s favorite subjects were the buffalo days of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

Whatever the stark differences in their backgrounds and expertise, Clarke and Ewers bridged such gaps through their mutual fascination with Blackfeet history and culture. Ewers came to Browning already primed with a deep interest in the tribe, kindled in graduate seminars led by Wissler, who himself had undertaken extensive fieldwork among the Blackfeet and other northern Plains groups in the early twentieth century. Thus, almost from the moment he arrived on the reservation, Ewers began cultivating what he called his “Indian informants,” members of the tribe in their eighties and nineties who had distinct memories of the buffalo days that so fascinated the young anthropologist. Years later he drew upon these oral histories as he wrote

The Blackfeet: Raiders on the Northwestern Plains

, published in 1958 and still considered the standard academic monograph on the tribe.

78

Ewers undoubtedly looked to Clarke as an expert on tribal history, even if Clarke was of a slightly later generation than men like Makes Cold Weather (b. 1867) or Chewing Black Bones (b. 1868), both of whom provided Ewers with extensive information about the lifeways of their people. Clarke had gifts the others did not—namely, the ability to shape with his hands what Ewers’s elderly informants could only describe with their tongues. Though published years after he had left Browning for an administrative post at the Smithsonian Institution,

The Blackfeet

reveals Ewers’s urgency to record the tribe’s ancient ways before they slipped into extinction, much as Edward S. Curtis had sought to do with camera and tripod earlier in the century (although Ewers traded much less in the “noble savage” mystique that suffuses Curtis’s work).

79

Clarke’s carvings and molds fit squarely with Ewers’s mission for the Museum of the Plains Indian.

Through it all and up to the very end of his life, Clarke never abandoned his chief artistic pursuit, drawing and sculpting western fauna. In fact, Ewers recalled with poignancy the last time he saw him, in 1969, a little more than a year before the artist’s death. Passing through the lobby of the majestic Glacier Park Lodge, Ewers spotted Clarke seated quietly near a stuffed mountain goat on display in a glass case, sketching the creature on a piece of paper. The anthropologist recalled, “I knew that Clarke must have carved scores of mountain goats—perhaps even hundreds—during his long career. But there he was—ever the perfectionist—keeping his hand in drawing that familiar animal from the model.”

80

As his daughter put it, Clarke was “an artist to the core.”

E

RECTED AT THE

turn of the twentieth century, the Montana State Capitol is a formidable edifice, built of granite and sandstone and capped by a copper-topped dome that soars 165 feet into the thin alpine sky above Helena. The interior is no less majestic, with beautiful paintings and sculptures that line the quiet marble hallways and preside over formal chambers and meeting rooms. Visitors who follow one of these corridors into the west wing of the building come eventually upon the Gallery of Outstanding Montanans, established in 1979 by the legislature “to pay homage to citizens of the Treasure State who made contributions of state or national significance to their selected fields of endeavor.”

On a cold spring day in 2003, officials and assorted guests assembled at the capitol for the induction of John Clarke, who took his place among such illustrious members as the actor Gary Cooper, journalist Chet Huntley, and Clarke’s old friend Charlie Russell, all of whom were in the first cohort of honorees. The citation for Clarke recognized not only his professional success but also his triumph over disability; it read in part, “Facing odds that would have deterred lesser men, he crafted a career as a renowned Blackfeet artist. His legacy survives as a worthy inspiration for all Montanans.” Kirby Lambert, spokesman for the nominating committee, emphasized the dual nature of Clarke’s achievement, adding that of the three dozen individuals so enshrined, “[Clarke] is one of my personal favorites.”

81

That a Clarke should enjoy such recognition seems fitting, in view of the outsize role the family played in the state’s history. Moreover, in 1865, Malcolm Clarke, John’s paternal grandfather, was among the twelve men who founded the Montana Historical Society, the body that selects new inductees for the hall of fame. And yet the elder Clarke and his associates never intended to honor individuals like his grandson. Rather, they established their organization to celebrate men just like themselves, white pioneers who, in conquering their own set of formidable obstacles—an unyielding physical environment, hostile native peoples—had prepared Montana for its eventual absorption into the United States. Their idol was perhaps Granville Stuart, a miner and rancher as well as a charter member of the MHS, who by the time he died in 1918 was acclaimed as “Mr. Montana” for his lasting contributions to the development of his adopted state, and as such was inducted into the Gallery of Outstanding Montanans in 1985.