The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (36 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

It is poignant and not a little ironic that John Clarke and Granville Stuart should share space in the Montana Hall of Fame, given that Stuart effectively renounced his own mixed-blood family in the late nineteenth century. Stuart had long worried that his interracial marriage would hold him back from material and social success, especially after the seismic demographic shift in Montana following the Civil War. Thus in 1890, less than a year and a half after the death of his Shoshone wife, Awbonnie, Stuart married a much younger white woman and four years later secured a prestigious diplomatic appointment as U.S. minister to Uruguay and Paraguay, an unthinkable development had Awbonnie lived, as his biographers note.

His abandoned children did not manage as well, especially two of his sons, who like Horace and Helen Clarke tried to keep their footing in both white and native worlds. Tom Stuart, Granville’s oldest boy, worked for a time on his father’s ranch, but incurred the older man’s wrath in his twenties when he forged Granville’s signature on checks and ran up expenses in his father’s name. In 1897 a Helena judge ordered Tom confined to the state asylum in Warm Springs, the result of a “threatening and uncontrollable temper” (stemming perhaps from epilepsy). He died there in 1905, just shy of his fortieth birthday. Tom’s younger brother Sam fared better, at least for a time, securing a job as a railroad engineer in the mid-1890s and marrying a Swedish woman. In the end he, too, ran afoul of the law and did several stints in prison before dying indigent at the state hospital in 1960.

82

It is possible, of course, to argue that John Clarke endured his own form of isolation, living on the Blackfeet Reservation during one of the bleakest periods in the history of Native America, when reservations across the country suffered grievously from scarcity and disease. So it was for Clarke, who as one visitor recalled spent his last years in relative poverty, living downstairs in his studio after the roof had burned off in a house fire, “napping on an iron cot, halfway under a tangle of old quilts and accompanied by a puppy or two, while an electric heater buzzed along too close for safety.”

83

Evidently, such marginal conditions failed to move everyone who passed by his home; in 1968 some teenagers visiting East Glacier Park broke into his studio and destroyed his tools and sculptures.

84

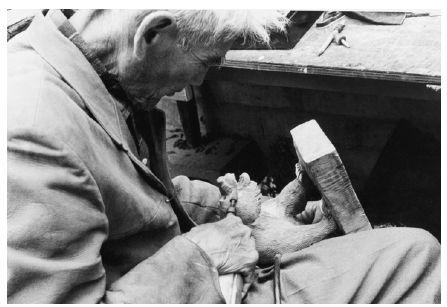

John L. Clarke, blocking out a bear, ca. 1961. Clarke carved almost until the day he died, in November 1970, at the age of eighty-nine, even after his eyes were clouded by cataracts and his hands gnarled by arthritis.

John Clarke made little attempt to accommodate himself to the new world forged by Malcolm Clarke and Granville Stuart. He found contentment in the rhythms of his daily life and work. Time and again, close friends and even casual acquaintances remarked on his equanimity, seen in his radiant smile, his unflappable patience, and his humbling generosity. Such was the judgment of Bob Morgan, the curator of the museum at the Montana Historical Society, when he stopped in at Clarke’s studio in 1969, shortly before Clarke died. The men had first met nearly three decades earlier, when Clarke had hocked small wood figurines during the Christmas season at the same upscale department store where Morgan, nearly fifty years younger, worked in the advertising and display department, sharing cups of coffee to stave off the bitter winter chill and passing notes back and forth.

On the occasion of their final visit, Morgan was unsurprised to find Clarke hard at work, absorbed in carving a small mountain goat. Clarke looked up and, recognizing his friend, smiled widely and extended his arm. “What a wonderful, gnarled hand to grasp,” Morgan recalled, “still strong and resolute.” They communicated in the old way, scribbling on a notepad; at one point Morgan, who was an aspiring artist himself, drew a deer head and passed it to John. Clarke replied with his own sketch of a rifle and wrote beneath it “no shells.” Stirred, it seems, by the elderly man’s circumstances, Morgan slipped him a few dollars, an act of charity that Clarke did not refuse, and wrote “you owe me a steak.” Clarke smiled, and they moved on to other subjects before Morgan bought a small bear for five dollars and headed out the door.

85

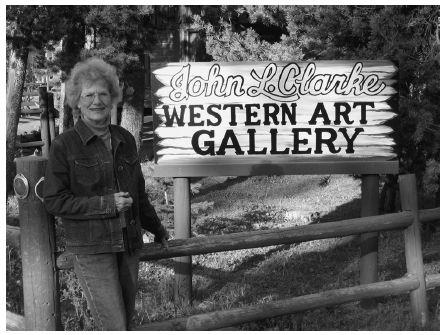

Clarke died in November of the following year at the age of eighty-nine, and was interred near Helen and Horace in the small family plot. His home studio languished for several years, until his daughter, Joyce—just like her great-aunt Helen—tired of California and moved, permanently, back to East Glacier. Upon her return to the Upper Missouri, Joyce discovered that her father’s home was too dilapidated to preserve but managed nevertheless to save some of the wood from the original building, which she incorporated into the design of the present structure, opened in 1977 as the John L. Clarke Western Art Gallery and Memorial Museum.

Inside, the gallery is warm and inviting, with soft lights and a plush rug that absorbs the footfalls of the many visitors who stop in during the tourist season, which runs from Memorial Day to the end of September, when the temperatures drop and the snow begins to fall. A few John Clarke originals are on display but not for sale, given Joyce’s ongoing attempts to buy back from museums and private collectors those sculptures of her father’s that she can locate and afford. In the back of the building, though, are several glass cases that feature a small sample of the artist’s tools as well as bronze casts made from miniature Clarke carvings, among them a playful bear cub caught in midstride and a Rocky Mountain goat perched on a ledge, with a muscled back and a shaggy beard. Beneath their alloy veneer and a thin coating of dust, they pulse with the life breathed into them by a master now four decades gone.

Joyce Clarke Turvey, 2007. John’s daughter, Joyce, opened a gallery in 1977 in East Glacier Park that honors her father and displays a small collection of his artwork. Photograph by the author.

I

n the summer of 1959, not long after John Clarke finished his masterpiece,

Blackfeet Encampment,

occupants of the Blackfeet Reservation noticed a white newcomer in and around Browning. Malcolm McFee was a graduate student in anthropology at Stanford University, but he was hardly a typical academic. Born in Seattle in 1917, McFee had dropped out of the University of Washington during the Depression to take a job selling plumbing supplies. After serving as a copilot on a B-29 during World War II, he returned to the plumbing business, working as an office manager at a Yakima firm until 1955, when—at the age of thirty-eight—he decided to go back to school and complete his undergraduate education. McFee was so taken with his studies that he opted to pursue a doctoral degree at Stanford, even though he was close to forty and had a wife and young son to support.

1

McFee had come to northern Montana that summer to do fieldwork among the Blackfeet, as Clark Wissler and John Ewers had before him. The Indians graciously opened their homes to the scholar, who became a virtual fixture among them over the course of the next decade, returning four more times to gather data. McFee dropped in at private residences and public ceremonies, usually armed with a notepad in order to record his observations. His research served as the basis for a scholarly article and a book, both considered classics of cultural anthropology today.

2

As McFee discovered, the postwar period on the Blackfeet Reservation was a profoundly troubled time, as it was all across Native America during the Termination Era of the 1950s and 1960s. If the Blackfeet did not suffer quite as much as groups like the Klamaths and the Menominees, who faced almost unimaginable poverty and high incidence of disease once federal welfare programs evaporated, conditions at Browning were nevertheless bleak, if not desperate. For instance, statistics from the late 1960s showed that the median annual income for a Blackfeet family was $1700, less than a quarter of the U.S. national average, and McFee reported that numerous Indian homes (especially in outlying areas) had neither electricity nor running water.

3

While these economic questions interested him, McFee was far more curious about cultural matters among the Blackfeet, to which he devoted most of his attention. What most intrigued him was the Indians’ demographic diversity, reflected in tribal enrollment figures from 1960. Those records indicated that of the 4,850 members living on the reservation, 13 percent claimed full-blood status and another 10 percent were less than a quarter Indian, revealing that the vast majority of enrolled Blackfeet were of mixed ancestry, a fact that had struck Ewers, too, just a few years earlier.

4

McFee wanted to know how the Blackfeet in this majority understood their hybrid identity, and after years of interviews and observation he concluded that such persons fell into two basic categories: a “white-oriented” majority and a smaller “Indian-oriented” group.

Divisions between the two populations, he noted, were marked not by biology or appearance but rather by values and behavior. White-oriented people prized hard work and material success, while their Indian-oriented counterparts cherished ceremonies and rituals aimed at preserving the tribe’s ancient ways. But, as McFee added in his most enduring assertion, some individuals on the reservation combined traits of both cultural groups. These he called “150% men,” explaining that in the case of such a person, “if, by one measure, he scores 75% on an Indian scale, we should not expect him to be limited to a 25% measure on another scale.”

5

In other words, one could be powerfully acculturated to both white and native ways simultaneously; the process was not a zero-sum calculation.

McFee’s book,

Modern Blackfeet: Montanans on a Reservation,

was praised even before its publication as “without doubt the most definitive piece written on a contemporary American Indian community.”

6

But if it was a major contribution to the anthropological literature, in some respects all that the author had done was to illuminate a longstanding demographic phenomenon: the enduring presence of peoples in between, those who were at once both red and white. Such individuals, of course, had existed since the earliest days of colonial America, counting among their number men like Thomas Rolfe, born in Virginia in the early seventeenth century to the English settler John Rolfe and his wife, Pocahontas, a Powhatan Indian. Or, closer in time and space to the Clarkes, consider the life of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, born during the voyage of the Corps of Discovery to a French Canadian interpreter and his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea. Meriwether Lewis became so enamored of the boy, whom he called “Pomp,” that Clark arranged for his education in St. Louis following the expedition.

In a foreword to McFee’s book, the series editor hailed the study as a rebuke to “the American mania for cultural uniformity,” referring, presumably, to the era that had just passed, the 1950s and early 1960s, a period marked by an apparent spirit of conformism that had flattened difference while imposing stifling orthodoxies.

7

But just as with the concept of the “150% man,” the impulse derided by the editor also had a long history in America, emerging in places where Europeans and their descendants achieved social and political dominance, even when they were outnumbered by nonwhite peoples. This process unfolded at different speeds, usually in response to the pace of white settlement—slowly at first in the East, but with blinding swiftness in places like the Rocky Mountain West in the period after the Civil War.

The tale of the Clarkes is so rich and instructive because it captures, in the history of a single such family composed of extraordinary members, the before-and-after qualities attendant to this transformation. Indeed, the world of Coth-co-co-na and Malcolm Clarke—one in which individuals of mixed ancestry stood near the pinnacle of the social order on the Upper Missouri, serving as brokers between white and native societies—was washed away in the course of a single generation. The Clarke children thus inherited a realm in which hybrid peoples were pushed increasingly to the margins by white newcomers, a process laden with physical as well as emotional violence.