The Small House Book (11 page)

Read The Small House Book Online

Authors: Jay Shafer

The phrase “E Pluribus Unum” (from many, one) appears elsewhere on the

bill along with no less than three other references to the archetype.

The common gable with a window at its center is vernacular architecture’s

one-eyed pyramid. The duality of its two sides converging at their singular

peak represents divinity, and is again underscored by a single central win-

dow. All of this rests on four walls, which are universally symbolic of the

cosmos.

85

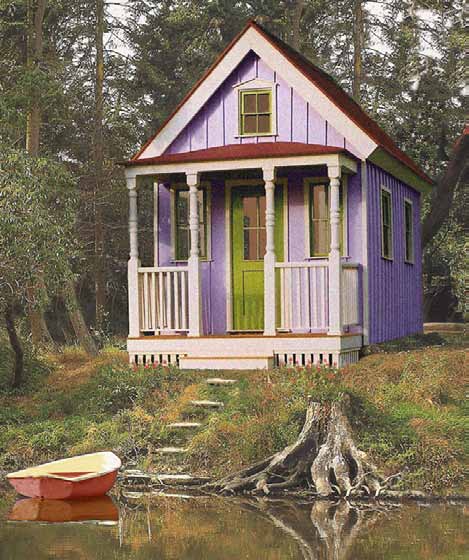

Tumbleweed Tiny House Company’s Epu with the wheels removed.

86

Form and Number

The meaning of numbers and shapes

is as universal as the use of the shapes

themselves. Those that turn up in nature

most often, like circles, squares, 1, 1.6, 2,

3, 4, 12 and 28 tend to be the most sym-

bolically loaded.

ONE

One

is a single point without dimension,

typically represented by the circle created

when a line is drawn around the point with

a compass. One symbolizes the divine

through its singularity.

TWO

Two

adds dimension through the addition

of a second point. It is commonly depicted

by the Vesica Piscis shape that occurs

when two circles overlap. It represents

duality and creativity.

Three

brings balance back to two. It is

THREE

represented by the triangle and symbol-

izes variations on the Trinity.

Four,

as embodied by the square, typi-

cally represents the world we live in, with

its four cardinal directions.

FOUR

87

Organizing Principles

The success of a work of art hinges, more than anything else, on the strength

of its composition. Here the term “composition” is used to mean “a whole

comprised of parts.” A strong composition is one in which all its parts work to

strengthen the whole. This is as true of a piece of music as it is of a painting

or the design of a small house.

The last chapter described subtractive design as the means to distilling a

house to its essential components. This chapter will focus primarily on how

the remaining parts are to be organized into a comprehensive whole. Seven

principles: simplicity, honesty, proportion, scale, alignment, hierarchy and

procession will be presented as essential considerations to meeting this end.

Simplicity

It is ironic that simplicity is by far the most difficult of the seven principles to

achieve. Simplification is a complicated process. It demands that every pro-

portion and axis be painstakingly honed and that every remaining detail be

absolutely essential. The more simplified a design becomes; the more any

imperfection is going to stand out. Everything in a plain design must make

sense, because every little thing means so much. The result of this arduous

effort will look like something a child could come up with. The most refined art

always looks as if it had been easy to achieve.

This sort of streamlining demands a firm understanding of what is neces-

sary to a home. As stated before, there is no room in an honest dwelling for

anything apart from what truly makes its occupant(s) happy. Each one of us

must ultimately decide what this is and is not for ourselves. But, as with all

good vernacular processes, we should first consider the findings of those

88

who have gone before us. While our domestic needs will differ as much as

our location and circumstances, a look at what others consider to be impor-

tant can get us going in the right direction.

Ideas about what is indispensable to a home can be concise so long as

they are kept abstract. Consider Cicero’s claim: “If you have a garden and

a library, you have everything you need.” And William Morris’ sage advice:

“Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe

to be beautiful.” More pragmatic lists tend to be a bit longer. Small house ad-

vocate, Ron Konzak, is helpful. In his essay, entitled: “Prohousing,” Konzak

explains that most every domicile should provide...

1. Shelter from the elements.

2. Personal security.

3. Space for the preparation and consumption of food.

4. Provision for personal hygiene.

5. Sanitary facilities for relieving oneself.

6. Secure storage for one’s possessions.

In their now-famous book,

A Pattern Language

, Christopher Alexander and

his colleagues provide a detailed list of no fewer than 150 items for possible

inclusion in a home. I have made a similar, albeit far less detailed, list here.

More asterisks indicate a more universal need for the item they accompany.

EXTERIOR:

1. A small parking area out back.

2. A front door that is easily identified from the street.****

3. A small awning over the door to keep occupants dry as they dig for keys

and guests dry as they wait for occupants.**

89

4. A bench next to the front door on which occupants can set things while

fumbling for keys or sit while putting on/off shoes.

5. A window in the front door.

6. A steeply-pitched roof to better deflect the elements.*

7. Adequate insulation in all doors, windows, walls, the floor and the roof.****

8. Windows on at least two sides of every room for cross ventilation and dif-

fuse, natural light.

9. Windows on the front of the house.**

10. A structure for bulk storage out back.

11. A light over the front door.

12. No less than 10 square feet of window glass for every 300 cubic feet of

interior space.**

13. Eaves

ENTRY:

14. A light switch right inside the front door.*

15. A bench just inside the front door on which occupants can set things while

fumbling for keys or sit while putting on/off shoes.

16. A closet or hooks near the door for coats, hats and gloves.*

A PLACE TO SIT:

17. A chair or floor pillow for each member of the household.****

18. Some extra chairs or pillows for guests. (In bulk storage?)*

19. A table for eating, with a light overhead.**

20. A table for working, with a light overhead.**

21. Nearby shelves or cabinets for books, eating utensils or anything else

pertinent to the activity area.

22. A private place for each member of the household.***

90

23. A phone.

A PLACE TO LIE DOWN:

24. A bed.***

25. A light at or above the head of the bed.

26. A surface near the head of the bed on which to set a clock, tissue, books,

etc.

APPLIANCES AND UTILITIES:

27. Electricity and a place for the accompanying fuse box.**

28. A source of water and sufficient room for water pipes.***

29. A water heater.**

30. A source of heat.**

31. A place for an air conditioner.

32. Ventilation and room for any accompanying ductwork (windows can

sometimes work to this end).****

33. An indoor toilet.*

34. A tub or shower.***

35. A towel rack near the tub or shower.**

36. A mirror.**

37. A home entertainment center.

38. A washer/dryer.

A PLACE TO COOK:

39. An appropriately-sized refrigerator.

40. A stove top.*

41. An oven.

42. A sink.***

91

43. A work surface for food preparation with a light over it.**

44. Shelves or cabinets near the work surface for food and cooking sup-

plies.**

ADDITIONAL BULK STORAGE:

45. A laundry bin.

46. No less than 100 cubic feet of storage per occupant for clothes, books

and personal items.****

These items are not mutually exclusive. Where one can serve two or more

purposes, so much the better. The dining table, for example, may double as a

desk. This is especially true in a one-person household, where a single piece

of furniture will rarely be used for more than one purpose at a time. Also,

keep in mind that many of these things can be tucked away while not in use.

This list is meant to be a starting place from which anyone can begin to de-

cide what is necessary to their own home. Certainly, what I propose to be

universal requirements will not be universally agreed upon. The only needs

that really matter in the design of a home are those of its occupant(s). The

important thing to keep in mind when creating one’s own list is that the less

significant a part is to the whole and its function, the more it will diminish the

quality of the overall design. Just remember when to say “when.”

92

Honesty

In the most beautiful houses, no attempt is made to conceal structural ele-

ments or disguise materials. Because wooden collar beams are understood

as necessary, they are also seen as beautiful. Whenever possible, features

like these are left unpainted and exposed to view. Then there are those hous-

es for which attempts are made to mimic the solid structure and materials of

more substantial homes. These are easily recognized by their wood-grain

textured, aluminum siding, hollow vinyl columns and false gables.

Aluminum is a fine material so long as it is used as needed and allowed to

look like aluminum. Artifice is artless. It does not merely violate nature’s law

of necessity, but openly mocks it. If wood is required for a job, wood should

be used and allowed to speak for itself. If aluminum is required, aluminum

should be used and its beauty left ungilded whenever possible.

Ornamental gables are to a house what the comb-over is to a head of hair.

The vast disparity between the intention and result of these two contrivances

is more than a little ironic. Both are intended to convince us that the home-

owner (or hair owner, as the case may be) feels secure in his position, but as

artifice, each only serves to reveal insecurity and dishonesty.

False gables are tacked onto the front side of a property in a vain attempt

to prove to us that the house is spectacular. While this effort is not fooling

anybody, it is effectively serving to weaken the structural integrity of the roof.

The more parts there are in a design, the more things can go wrong. Leaks

almost never spring on a straight-gabled roof, but in the valleys between

gables, they are relatively common. Unnecessary gables compromise sim-

plicity for what is bound to be a very expensive spectacle.

93

Proportion

If these principles are starting to seem a lot like common sense, it is be-

cause they are. It is in our nature to seek out the sort of order that they

prescribe. Honest structure and simple forms strike a chord with us because

they are true to nature’s law of necessity. Sound proportions strike a chord,

too. Certain proportions seem to appear everywhere — in sea shells, trees,

geodes, cell structure, and all of what is commonly called “the natural world.”

That these same proportions continually turn up in our own creations should

not seem too surprising or coincidental. We are nature, after all, and so our

works are bound to contain these natural proportions.

Proportioning is one of the primary means by which a building can be made

readable. Repeated architectural forms and the spaces between them are

like music, the pattern (or rhythm) of which we understand because it is al-