The Small House Book (12 page)

Read The Small House Book Online

Authors: Jay Shafer

ways with us. We intuitively understand good proportions because they are a

part of our most primal language.

On the most conscious level, good proportion is achieved by first choosing

an increment of measure. Making such a seemingly arbitrary decision can

be made easier if meaning is imposed on it. Ancient civilizations created sys-

tems of measure based on human and geodetic significance. A Mediterra-

nian precursor to the foot we use today was 1/360,000 of 1/360 (one degree)

of the circumference of the earth. It was also related to the conventional

calendar containing 360 days of the year plus five holy days, and it was 1/6

the height of what were viewed as ideal human proportions. The eighteen-

inch cubit (distance from elbow to longest finger tip) and the yard (1/2 of the

total height) also relate to this canon. We have inherited a measuring system

imbued with meaning that relates us to our environment. Our buildings are

94

literally designed to embody the characteristics of the Self.

Today, plywood is milled to 4’ x 8’ pieces; lumber comes in 6’, 8’, 10’, 12’ and

16’ lengths; metal roofing is typically 3’ wide, and most other building materi-

als are similarly sized to fit within this one foot system of measure. Great ef-

ficiency can be achieved by keeping this in mind during the design process.

A large share of bragging rights deservedly go to a designer whose structure

has left little construction waste and has required relatively few saw cuts.

Simplified construction is nearly as much the aim of subtractive design as

simplified form and function are.

The unit of measure we use to compose a harmonious design can be more

than just linear. In Japan, a two-dimensional increment called the “tatami

mat” is often used. It is an area of three by six feet (the Japanese foot, or

shaku

, is actually 11.93 of our inches). This area is meant to correlate with

human dimensions. The Japanese saying, “tatte hanjo, nete ichijo,” trans-

lates as, “half a mat to stand, one mat to sleep.”

Once an increment has been chosen, be it a foot, yard, cubit, tatami mat or

a sheet of plywood, we can begin to compose a home comprised of simple

multiples and fractions of the unit. This process should be fairly intuitive.

Each one of us will compose somewhat differently, but our underlying prin-

ciples are the same. These principles are not arbitrary, but the same that

govern the composition of all natural things.

95

Dee Williams’ house in Olympia, WA

96

Scale

Always design a thing by considering it in its next larger context—a chair in a

room, a room in a house, a house in an environment.

–Eliel Saarinen

Again, the scale of our homes should be determined by the true needs of

their occupant(s). Few of us would go into a restaurant and seek out a table

in the large, open space at the center of the dining room. Most of us pre-

fer the comfort and security of the corner booth. Ideally, every room in our

homes will offer the same sense of enclosure without confinement.

To be sure that a minimized space does not feel confining, its designer has

to consider ergonomics and any pertinent anthropometric data. Understand-

ing exactly how much space we occupy when we sit, stand or lie down is

absolutely essential to the subtractive process. To know how much can be

excised from our homes, we must first understand how much is needed. An

extensive list of recommended dimensions is provided on pages 117 - 122.

When a home’s designer is also to be its sole inhabitant, a more personal-

ized list can be made. Every measurement within a house, from the size of

its doorways to the height of its kitchen counter, should ideally be determined

by what feels good to the occupant. Designing one’s own little house is more

like tailoring a suit than what is normally thought of as architecture.

The overall scale of our homes does not need to accommodate every pos-

sible activity under the sun. With little exception, home is the place we go

to sit and to lie around at the end of each day. There will also most likely be

some cooking, eating, hygiene, working and playing going on, but none of

these activities needs to occupy a palace. Remember, “half a mat to stand,

one mat to sleep.”

97

Alignment

Gestalt psychologists have shown that compositions with long, continuous

lines make more sense to us than those with a lot of little broken ones. Con-

tinuity allows us to read a composition as a whole. The principle of alignment

is just one part of what some psychologists have termed the “simplicity” con-

cept. This states that simple patterns are easier for us to comprehend than

complex ones. This will come as no surprise to vernacular architects, who

have been putting the concept to work for quite some time now. Common

sense has always been the folk designer’s greatest asset.

Alignment entails arranging the elements of a design along a single axis or

arc whenever possible. When a group of columns is required, a savvy de-

signer will not just put one over here and arbitrarily plop the next two down

wherever chance or ego dictates. The designer will line them up in a row. The

geometry of alignment may contain some real lines, like the kind produced

by a solid wall, and it may have some implied ones, like the axis that runs

through a row of well-ordered columns.

Hierarchy

Good home design entails a lot of categorizing. The categories we use are

determined by function. In organizing a home, everything that is used to

prepare food would, for example, most likely go into the “kitchen” category.

If something in the kitchen category functions primarily to wash dishes, it

would probably be placed into the subcategory of “kitchen sink area.” The

categories proposed by our predecessors usually serve as pretty good tools

for organizing a home. Ideas like “kitchen,” “bathroom,” and “bedroom” stick

around because they generally work. But these ideas cannot be allowed to

dictate the ultimate form of a dwelling; that is for necessity alone to decide.

98

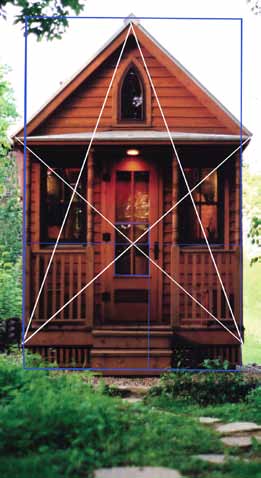

Sacred Geometry

Organizing the tops of windows

and doors along a horizontal axis

and deliberately spacing porch

posts in a row are examples of the

ways alignment and proportion can

be consciously used to create a

structure that makes visual sense.

Less obvious examples become

apparent when regulating lines are

drawn on photos of a building’s fa-

cade. These lines are stretched

between significant elements, like

from the peak of the roof to the

cornerstones, or from a keystone

to the baseplates. When geom-

etry has been allowed to dictate

the rest of the design, the lines will

almost invariably intersect or align

with other crucial parts of the build-

ing. The intersections are often

unexpected, their appearance the

unintended biproduct of the cre-

ative process described on these

pages.

99

Do not think that, just because our shared idea of “bathroom” includes a bath,

a sink and a toilet, that these things must always be grouped together behind

the same door. The needs of a particular household may determine that each

be kept separate so that more than one can be used at a time. What is more,

if the kitchen sink is just outside the door to the toilet, then a separate basin

may not be necessary at all. The distinctions made between the categories

of “living room,” “family room” and “dining room” might well be combined into

the single category of “great room” for further consolidation.

Vernacular designers do not thoughtlessly mimic the form of other buildings.

They pay close attention to them, use what works in their area, and improve

upon what does not.

Along with all the categorizing that goes on during the design process, there

is a lot of prioritizing that has to be done as well. The relative importance of

a room and the things in it can be underscored by size and placement. The

most important room in a small house, in both the practical and the symbolic

sense, is almost always the great room or its farmhouse kitchen equivalent.

To make its importance all the more clear, this area should occupy the largest

share of the home and should be prominently located. In a small dwelling, it

is generally best to position this space near the home’s center, so that small-

er, less significant rooms can be arranged around its periphery as alcoves.

Arranging the rooms and objects in a house according to their relative impor-

tance is essential to making any space readable. Presenting such a hierar-

chy may require that some doorways be enlarged to exaggerate one room’s

significance, or that a ceiling be lowered to downplay another’s. As always,

necessity will determine these things inasmuch as it is allowed to.

100

Procession

While the principle of procession is still primarily about space, it also pertains

to time. The best houses speak to us in a visual language with which we are

all familiar. A gate in a picket fence that opens onto a narrow path that leads

through a yard to an open porch that covers a door is a set of symbols we rec-

ognize as signposts guiding us through increasingly private territory towards

the threshold of someone’s clandestine world. Such “layering” (as it is often

called) demarcates public space from semiprivate and private spaces. This

serves to put us at ease, as it ensures that we will never be left to wonder if

we have overstepped our boundaries as guests. Familiar symbols of domes-

ticity, like the gable, can further comfort us by presenting the subconscious

with the familiar language of home. A covered doorway that is clearly visible

from the street not only lets us know where to enter a house, but indicates

that we are welcome there. Generally, more private areas, like bedrooms and

bathrooms, will be positioned towards the rear of a house and encountered

only after more public realms, like the living room, have been passed.

Once inside a good dwelling, visual cues should leave us with no doubt that

this is a home in the truest sense of the word. Some of the greatest residen-

tial designs employ the same formal geometry as that of sacred architecture.

When we approach and enter a well-designed church or mosque, we imme-

diately find ourselves straddling its vertical symmetry. As we follow the axis

between our eye and the cross or qibla at the far end of the room, we remain

at the building’s center. This procession alludes to the structure’s significance

as a symbol of the cosmos of which we are the center. A well-designed little

house will remind us just as effectively as any cathedral that we are not

merely witnessing divine beauty, but that we are that beauty.

101

A strong procession is created in the home by using some variation of the

same three elements that are universally used to create it in sacred architec-

ture: a gate, a path and a focal point. Moreover, all seven of the principles

that have been presented here for residential design are none other than