Writing Movies For Fun And Profit! (21 page)

Read Writing Movies For Fun And Profit! Online

Authors: Thomas Lennon,Robert B Garant

So

how do you write a screenplay?

Remember (in YODA VOICE):

“You don’t, foolish and reckless boy … there is only writing outlines.”

Now, when we say “outline,” we don’t mean a few notes on a cocktail napkin. Sure, that’s a great way to write Charles Bukowski poems, but Charles Bukowski already wrote those.

We mean write out the whole movie

. Almost everything that happens, minus dialogue, should be in your outline. Your outline should be long. (Ours run around 20 pages.) It seems like silly mathematics, but the longer your outline is, the more problems you’ve worked out in advance and the less likely you’ll hit a wall while you’re writing the actual screenplay. Keep in mind, if you have an outline, there should be NO WRITER’S BLOCK. You know exactly where you’re going and what the next scene is, and you never have to slow down (except to watch funny cat videos).

For the level of detail we’re talking about, see the sample outlines in the appendix at the end of this book.

Of course, things will change from your outline to your finished screenplay; this is the nature of the creative process. But if there’s a problem, it’s way easier to remedy in the

outline

stage. When you’re in the actual screenplay stage, problems that arise become a game of Jenga—undoing work in your screenplay is time-consuming and frustrating. Remember: always write an outline. Fixing a blueprint is a lot easier than fixing a skyscraper. Get the hard stuff over with in the outline. Then spend the time you save eating at

Jules Verne Restaurant

Eiffel Tower, Paris, France

It’s a truly “special occasion” restaurant inside the Eiffel Tower. But when you’re a wealthy screenwriter—

every day is a special occasion

!

Even when you’re writing a spec, you must always:

HAVE A DEADLINE!

You must have a deadline

. Exclamation point. If you don’t have a deadline, you’re not writing for a living, you’re writing as a hobby. Deadlines are extraordinarily helpful. Make a deadline for yourself, and

stick to it

. As we said in

Chapter 5

, when you’re writing for the studios, you get ten weeks to turn in your first draft. This makes writing for the studios supereasy, ’cause if you’re not done in ten weeks—YOU’RE IN BREACH OF CONTRACT, AND THEY CAN SUE YOUR ASS. Yikes!

Now, then, can you have an outline and a deadline and still fail? Of course. Your film could have an inherent flaw you didn’t think of. Or as mentioned previously, it might not be like the KINDS of films showing at the multiplex right now. But if it is and you have an outline and a deadline, the odds are stacked in your favor!

*

WRITING ACTION AND DESCRIPTION

Our only advice about writing action and description in your script:

Keep it simple.

Now, if we had any sense of wit at all, we would have ended the chapter right there. But … we don’t. (No surprise. You’ve seen

Herbie: Fully Loaded,

right? VW Bug follows Lindsay Lohan around? They win the big race against Jeff Gordon at the end? Oscar Wilde we ain’t.)

To the point, when it comes to your descriptions in your scripts—about locations, characters, and action sequences: keep them brief. Don’t get poetic, just tell people what they need to know. Describe things perfectly, yet economically.

For example, in describing your

locations

: After every slug line for a location …

EXT. WAREHOUSE—NIGHT

…you then need to describe the warehouse:

A dark, abandoned warehouse on a seedy pier. An SUV is parked beside it, engine running.

THAT’S ALL YOU NEED. Just the KEY information. Don’t go on and on and on about “the eerie moonlight dappled through the trees” or the “lonely sense of forboding that seems to emanate from the very timbers of the ramshackle yet somehow lovable old building.” NO. If you do:

1. People will start skimming forward through your script, and they might MISS something that’s actually important to the story. And—

2. People will think you’re VAMPING—stalling, padding out the pages—because your story isn’t any good. People don’t go to the multiplex to see dappled moonlight. They go for STORY, ACTION, and great CHARACTERS.

GET TO THE POINT.

Keep your descriptions very brief and very clear. No one wants flowery prose. The point of your descriptions is not to look good on the page. The point is to describe things in a way that makes everything VERY easy to picture. Easy to picture for people who’ve already read ten terrible scripts that day BEFORE yours. People who might not be the brightest potato on the porch in the first place. There aren’t a lot of actors and directors in Mensa—

keep it simple, stupid.

If it takes longer than an hour to read your script—NO ONE IN HOLLYWOOD WILL HAVE THE FOCUS FINISH TO IT. Dialogue reads FAST. Your paragraphs of descriptions should read faster. Most of the movie stars you hope will read your script CARE ONLY ABOUT THEIR DIALOGUE.

When writing description in your movie,

Think Hemingway—not Joyce.

Yes, it needs to pop off the page with zing and style, but it needs to be

SHORT, CLEAR, and VERY, VERY READABLE

.

For your

character descriptions

:

See

Chapter 24

, “… How to Formulate Characters in a Script,” and remember, you have the first 10 pages of your script to introduce your character. You don’t need to do it all in

the first paragraph. Any paragraph that takes up a sizable chunk of the page is TOO LONG.

For your

action scenes

: No one can tell you how to CREATE a good action scene—you have to learn to do that yourself, through living your own adventures, studying action sequences in great films, reading good books, and perhaps some moderate to heavy drug use.

But—when WRITING AN ACTION SCENE DOWN, our tip is this:

Clarity clarity clarity.

If it’s a car chase or a scene with a T-Rex drinking at a water fountain, then running after Ben Stiller, say it in as few words as possible.

Say only what you NEED to say to set and describe the action scene

.

If your scene has a hundred guys who AREN’T lead characters, all shooting at one another—DON’T DESCRIBE THE ACTION OF EVERY SINGLE GUY. That’s maddening to read and impossible to follow. Write something like:

More GIs pour out onto the beach, as Nazis mow them down from their concrete bunkers. It’s a MASSACRE: GIs drown in hails of underwater bullets; a GI with a flamethrower explodes in flames, killing the entire platoon in his landing craft.

Then talk the audience through what HANKS and SIZEMORE are doing.

Don’t get hung up in details. Don’t get hung up in technical jargon or descriptions of “rippling biceps.” Write only the things that the reader needs to know to PICTURE the action scene.

Oh, and if it’s an action scene, it also needs to be:

AWESOME.

Action scenes are very expensive.

An interesting side note about action scenes: if you write an action scene well, it might end up being the one thing in the movie that actually resembles your script.

Why? Because it will most likely be directed by a second unit director and planned by the stunt coordinator and the CGI guys. And they don’t read a script and automatically start figuring out how to change it. They read a script and figure out how to execute it.

Also, the big action scenes are usually planned FIRST, so that the CGI can be done in time. So sometimes the action scene you wrote is done before the director has even finished the OTHER projects he’s working on. He hasn’t moved to your movie full-time yet. And CGI is very expensive to change.

If you write a great action scene, there’s a good chance it might end up in the final film, just the way you intended—only because it was started and planned while the director was still half asleep.

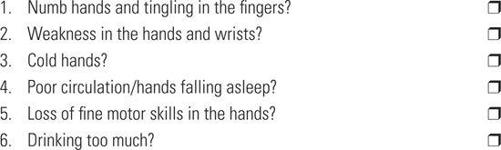

SCREENWRITING PROGRESS WORKSHEET

(Check all that apply)

If you checked any, most, or all of these boxes—CONGRATULATIONS, you have carpal tunnel syndrome! (And possibly a drinking problem.) Your median nerve has become compressed at the wrist, and it’s a sure sign that you’re finally writing enough to make it as a Hollywood screenwriter! Well done, let’s high-five! (You won’t feel it.)

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a serious condition, and there are steps for minimizing the pain and damage done to the nerves in your wrist, but offhand we don’t know what those steps are. You should probably ask a doctor or sumpin’. But it SEEMS like you’re supposed to wear those fruity-looking carpal tunnel gloves. We SKIP THE GLOVES and treat it the old-fashioned way: with moderate to heavy drinking, or what the Irish call “pint lifting.” Drinking puts your hand and wrist into a totally different position from writing and is the number one treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome relief that doctors recommend.

*

For more information on carpal tunnel syndrome, Google it, like a normal person. And while you’re at it, Google Helen Mirren > Images > Safe Search OFF.

ADVICE FOR WRITING WITH A PARTNER

We’ve been writing together for twenty years. We used to do it the hard way. Now we do it the fun and easy way. We would like to impart this fun and easy way to you. It took us a decade to figure it out. You will learn it by the end of these few pages.

The key to writing with a partner is: use the fact that there are two of you as an asset, not a hindrance. Some writing partners write together in the same room, taking turns who types while the other one paces or sits, quill in mouth, gazing dreamily out the window as the mist rises on the moor.

This is crazy. Nothing is worse than typing with someone looking over your shoulder.

Nothing

.

Plus, you know that little voice in your head that judges everything you write as you write it, that says, “That’s wrong,” “That should be a ‘then’ instead of an ‘and,’”“

That should be in italics,

”“Wait, no, it shouldn’t.” When you both write in the same room, you have TWO of those little voices in the room instead of one.

Instead of writing twice as fast, you’re writing twice as slow.

So—how do you write twice as fast? Easy.

First, write an outline of your movie. (See

Chapter 25

, “How to Write a Screenplay.”) Figure out the entire movie, and write it out in an in-depth outline. This you need to do together. We usually write our outlines in a bar so we can drink beer and look at girls. That takes the edge off—and you’ll be shocked to find how many jokes are lurking in the bottom of your third or fourth beer. (See

Chapter 33

, “I’m Drinking Too Much. Is That a Problem?”)

Then, when the outline is done, split it up into little sections. Usually a page or so of an outline will end up being between seven and ten pages of script. Split your outline up into page or so sized sections. Make sure that the sections have natural, logical ins and outs. (Don’t split a love scene or an action sequence in half, for example.)

When your outline is divided into twenty or so sections, flip a coin; one of you does the ODD sections, the other does the EVEN sections.

Then go to your separate homes (Tom has a writing compound in Barcelona; Ben has a small writing isthmus in the French Marquesas) and write your first section.

Then e-mail it to your partner. Then attach their first section to yours. Then read the whole script (parts 1 and 2) and tweak it a little: make it better, faster, funnier. Cut jokes you don’t like, or make them better.

Then write your next section, part 3. Attach it. Repeat, polishing parts 1 through 3. Etc., etc., etc.

Soon you will have the whole script written—in half the time it would have taken you to write it alone or working together, looking over each other’s shoulders.

Not only that, but by the time you get to the end of your script, you will have done twenty passes of the script, polishing it. Your FIRST draft is really your twentieth.

Neat, huh?

People ask us, “But don’t you argue when you cut out each other’s jokes?” No. We don’t. If one of us cuts a joke we like, we put it back. If it gets taken out AGAIN, we don’t put it back. It’s that easy.

For this to work, you have to follow these four rules:

1. You and your partner must trust each other.