You Majored in What? (24 page)

Read You Majored in What? Online

Authors: Katharine Brooks

Experimental wanderings are some of the most fun you can have in the job search. Some of them will be obvious and directly career related, such as an internship in your chosen field. But others will be just about you having fun doing what you like to do and encountering a chance connection or lead that will move you closer to your dream. Consider the story of Hannah:

Just prior to leaving school for the holidays, Hannah’s handbell choir performed a concert at a local church. At the end of the concert, the minister asked the choir to introduce themselves to the congregation. Most people just said their names, but on a whim Hannah said, “I’m Hannah and I’m a Russian area studies major, and I just returned from a year in Moscow and would love to go back again.” The audience smiled and clapped. Hannah thought nothing more about it until a woman stopped her as she was leaving the church and said, “My husband is an executive with a local company that is just starting to do business in Russia. Would you like to meet him?” Hannah, of course, said yes, and the woman gave her the executive’s home phone number. Hannah called him that evening, and a few weeks later she was on a plane to Moscow, escorting several company executives on a two-week fact-finding trip. She translated for them, showed them around the city, explained how many services worked, and even sat in on confidential meetings. When she returned for spring semester, she interned with the company and received a job offer at graduation.

Let’s take a moment to analyze what Hannah did right:

1. She was doing something she loved: playing in a handbell choir.

2. She seized the opportunity to let a group of people know what she was seeking.

3.

She didn’t ask for a job.

This is an important point to remember because timing is everything. Obviously, she was ultimately seeking a job, but if she had said, “I need a job,” the executive’s wife might not have even approached her because she wouldn’t have known if her husband had any jobs. Hannah simple phrased her desire more like an intention, “I’m looking for a way back to Russia,” which opened the gate to the job path.

Hannah’s situation worked out beautifully. But not all experimental wanderings do, as in the case of Andrew, who wanted to work in South America.

Through a chance encounter on an elevator, Andrew met a gentleman who had some connections in Argentina and told him about an opportunity in market research for a dental organization. Andrew applied for the job and was told to report in about a month. He took off for Buenos Aires, excited about the prospect of working in his dream country. He vacationed and traveled for a few weeks first and then reported to his new job. Unfortunately, his dream quickly disintegrated when on his third day at the job (which turned out to be in a dentist’s office), he was handed a book of dental procedures and told to read it and be ready to work as a dental assistant in one week. He protested his lack of knowledge and skill in this area and shuddered at the thought of cleaning people’s teeth, but no one cared. He realized that because they were paying him in cash and he technically didn’t have the proper working papers, he had no power to do anything. In two days he would have to sign a contract that would keep him there for six months, so he quickly packed and took a flight back to America. Now, it would be easy to call this experiment a failure, and Andrew did feel frustrated and angry when he returned home, but within a few days he had decided he could turn his experience into something good. First, he had traveled all over Argentina, which he had always wanted to do, and second, he had strengthened his language skills. Moreover, he had a great story to tell a future employer. He even wrote a short essay for the career center at his college to help students prepare for an international job. He decided to pursue another of his Possible Lives: becoming a Spanish professor. He has enrolled in a master’s program in Spanish (he used his Argentina story as his essay) and will remain to get a Ph.D. And now that he can laugh about the experience, he has a great educational story for his students.

What did Andrew do right ?

1. He engaged with someone who helped him find an opportunity in a country he had always wanted to see.

2. He took a chance and reached for his goal.

3. Once he discovered unforeseen problems, he made quick decisions and cut his losses.

4. He used his negative experience to catapult himself forward into a new and better experience.

Andrew’s and Hannah’s experiences confirm the value in approaching all your experimental wanderings with two questions: What can I learn? and What stories could I tell about this experience? By constantly considering what you’re learning and the story you will tell, you mine the experience for its learning value regardless of whether it is positive or not.

Most students enjoy experimental wanderings (particularly when they discover how interesting and valuable they are), but if you’re a little anxious about it, try using one of the metaphors discussed earlier and casting yourself in a role—it might help you detach yourself from your anxiety. Why not focus on being curious? Curiosity can take you a long way in the job search process and a little curiosity might be all you need to take a step forward. Remember the positive mindset in Chapter 3? What if you replaced worry with wonder? The key to finding experiments is asking questions such as How could I . . .? or What’s great about . . .?” or

→ What would happen if

• I wandered into that program tonight at the college and asked the guest speaker how she or he first started?

• I started writing a blog about my interest in foreign policy?

• I took a semester off to test out my dream?

• I called a graduate who’s a social worker to find out whether or not I really need to get that M.S.W. degree?

Or

→ I’m curious:

• Just what do I need to do to be able to____?

• How could I make a better learning experience out of thi____?

• What are the salaries of____?

• Would I really like working with____?

• Where is the best place to work if I’m interested in____?

The point of the experimental wanderings is to move you forward. There aren’t any rules per se about these wanderings, because there’s no way to predict what experience or research finding will be the key to your future. So the best thing you can do is take action. Doing something, anything, may move you a step closer to your dream. Here are some guidelines that should spur you on to start experimenting immediately.

TEN GUIDELINES FOR EXPERIMENTAL WANDERINGS

1. Wander anywhere.

2. Wander anytime.

3. Say yes.

4. Forget perfect. No experiment is a failure if you’ve learned something.

5. Assume there will be messiness, detours, blind alleys, and new adventures.

6. Be sure to actively engage:

a. Express an opinion.

b. Speak for someone who can’t.

c. Provide a solution.

d. Focus on and state what you want.

e. Ask how you can help.

f. Ask good questions.

7. Find the story.

8. Be curious.

9. Be flexible.

10. Seek part of your dream if the whole dream isn’t available.

It’s hard to add one more commitment to an already overcommitted schedule, so design your experiments to fit with your schedule. You’re less likely to experiment if the cost seems too great for the benefit. Don’t set yourself up for ten hours a week of volunteering if you don’t have the time. Find a volunteer project that you can do in an afternoon. You’ll get a taste of whether you like it and can add more time as you go along. The trick is to take some sort of action. You can audition for a Possible Life without committing to it. You define the level of commitment—one hour, one day, one semester, or one year. As you experiment, be sure to pay attention and look for the stories and possible career touchpoints: moments of contact with potential employers. Remember Hannah as you make your connections: don’t ask for a job—talk about what you’re looking for. Just treat everything as an experiment and see what happens.

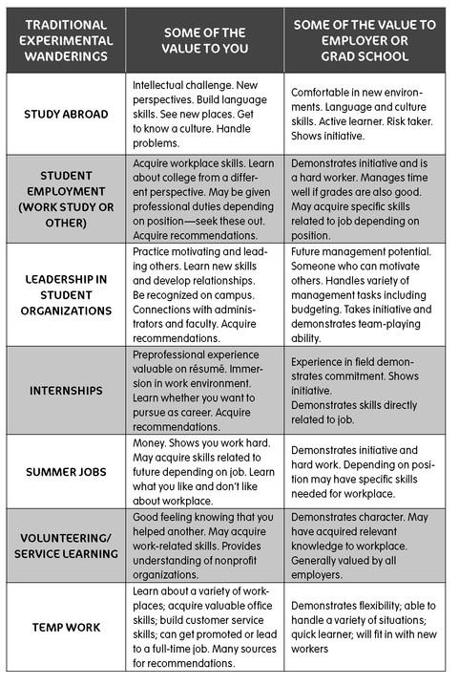

TRADITIONAL EXPERIMENTAL WANDERINGS

There are several well-known traditional sources for experimental wandering that many students have found helpful. One reason they are successful is that they tend to be longer-term experiences that give you time to really gain new knowledge and develop your skills in a particular field. You can also list them on your résumé under the experience category (see Chapter 8), regardless of whether you were paid or not. Employers like seeing these experiences because they demonstrate commitment; they show that you successfully complete an experience and that you are hardworking and focused. The chart on the next page illustrates the top seven experiences you can acquire and their value to both you and the employer:

SEEKING THE BUTTERFLY: FIFTY-PLUS LESS TRADITIONAL EXPERIMENTAL WANDERINGS

The goal of experimental wandering is to put yourself in a place where something might happen.

Everyone knows the phrase “six degrees of separation”:

the notion that you are only five people away from anyone you want to meet. You never know who might know someone who could help you. So as you pursue these experimental wanderings, keep Hannah’s lead in mind: whatever you’re doing, introduce yourself, and state what you’re seeking (avoid

job

—use

experience

or another word). Ask yourself: Who am I connected with already? Have I used my current connections to find opportunities? And if you’re considering something new, ask yourself: What could I do? How could I help? What could I learn from this? What is the story?

Below is a list of over fifty experimental wanderings, in no particular order, many of which might not seem job-search related. Remember your overall goal is to collect information and learn, and these activities can help you by either contributing to your understanding or knowledge of a subject, or connecting you to people who can help you. As you read the list, highlight the ones you’d like to try first or jot them down in your notebook as intentions or goals. And add your own as well!

JOIN, INTERACT, AND MEET PEOPLE

• Talk to everyone you know or meet about your plans for the future.

• Join or create an organization and demonstrate your unique gifts and talents.

• Take on tasks you enjoy and build your résumé.

• Shadow someone: spend a day with a person doing what you want to do.

• Do an externship: spend a week or two with an alumnus in your field of interest.

• Put yourself in a place where you’ll meet the people you want to meet. When asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton said, “Because that’s where the money is.” If you want to work in_ , where are the people who are already working in that field? Find out where they hang out and go there. If you’re over twenty-one, bars can be a great place to connect. There are several bars in Washington, D. C., that are known as hangouts for congressional aides and political types. Police usually have a favorite watering hole, as do newspaper reporters. Doctors and nurses might stop for a quick after-work drink in bars or restaurants near the hospital. Traveling business executives often stop for a drink in the bar of a five-star hotel. In Austin, Texas, where I live, there’s a chili parlor frequented by lawyers, judges, legislators, and others who work in the capitol nearby.

• Join a team—whether it’s sailing or the chess club, you will meet people.

• Sing in a choir or play in an orchestra.

• Pursue a hobby with others.