Ancient Iraq (28 page)

Hurrians and Mitannians

Known ninety years ago from one single cuneiform text (a letter found at el-Amarna in Egypt) and from a reference in the Bible (the ‘

Horites

’ of

Genesis

xxxvi. 20 – 30), the Hurrians have become a subject of considerable interest to historians and archaeologists. Unlike the Hittites, they played little part in Near

Eastern politics until the fifteenth century

B.C.

, and then only for a short period, although there is now ample evidence that they formed an important and active element in the population of Mesopotamia and Syria during the second millennium

B.C.

Yet they still remain in many respects an elusive people, and what we know of them can be told in a few words.

14

Their language, written in cuneiform script, is neither Semitic nor Indo-European, but belongs to the vague so-called ‘Asianic’ group, its nearest relative being Urartian, the language spoken in the country of Urartu (Armenia) in the first millennium

B.C

. Their national gods were Teshup, a storm-god of the mountains, and his consort Hepa, a form of mother-goddess. Whether the Hurrians had an art of their own is open to discussion, but the ceramics associated with their presence in certain sites are most characteristic. These elegant goblets decorated with flowers, birds and geometrical designs painted in buff colour on a dark-grey background contrast with the plain Mesopotamian pottery of the time and date a level as surely as did the Halaf or Ubaid painted wares in proto-historic ages.

Language and religion point to the mountainous north, more precisely to Armenia, as the original homeland of the Hurrians, but they were never strictly confined to that region. We have already seen (p. 156) Hurrian kingdoms established on the upper Tigris and on the Upper Euphrates during the Akkadian period. Under the Third Dynasty of Ur isolated personal names in the economic records from Drehem, near Nippur, suggest that the Hurrians formed in Sumer small groups of immigrants comparable to Armenians in modern Iraq. During the first quarter of the second millennium Hurrian infiltrations in the ‘Fertile Crescent’ amounted, at least in some regions, to a peaceful invasion. In the Syrian town of Alalah, between Aleppo and Antioch, the Hurrians formed the majority of the population as early as 1800

B.C

.

15

At the same time Hurrian personal names and religious texts in Hurrian are found in the archives of Mari and Chagar Bazar. A century or so later the Hurrians practically possess northern Iraq. They occupy the city of Gasur,

near Kirkuk, change its name into Nuzi, adopt the language and customs of its former Semitic inhabitants, and build up a very prosperous Hurrian community.

16

Tepe Gawra and Tell Billa,

17

near Mosul, equally fall under their influence. After 1600

B.C

. the Hurrian pottery replaces the crudely painted pottery peculiar to the Khabur valley, and the Hurrian element dominates in northern Syria, northern Iraq and Jazirah. We should therefore not be surprised to find in those regions, at the beginning of the fifteenth century

B.C.

, a Hurrian kingdom powerful enough to hold in check the Assyrians in the east, the Hittites and Egyptians in the west. The heart of this kingdom lay in the Balikh-Khabur district, in the region called

Hanigalbat

by the Assyrians and

Naharim

(‘the Rivers’) by the Western Semites, and it is probable that the name of our ‘Hurrians’ (

Hurri

) survived in Orrhoe, the Greek name for modern Urfa.

In a number of texts the Hurrian kingdom of Jazirah is called

Mitanni

, and from this word derives the appellation ‘Mitannian’ applied to the Indo-European element discernible in the Hurrian society at a certain period. We do not know when and how the Indo-Aryans came to be mixed with the Hurrians and took control over them, but there is little doubt that, at least during the fifteenth and fourteenth centuries

B.C.

, they were settled among them as a leading aristocracy. The names of several Mitannian kings, such as Mattiwaza and Tushratta, and the term

mariannu

, which is applied to a category of warriors, are most probably of Indo-European origin. Moreover, in a treaty between Mitannians and Hittites, the gods Mitrasil, Arunasil, Indar and Nasattyana – which are, of course, the well-known Aryan gods Mithra, Varuna, Indra and the Nasatyas – are invoked side by side with Teshup and Hepa. Undoubtedly it was those ancient nomads of the Russian plains who taught the Hurrians the art of horse-training – a Hurrian living in Boghazkoy wrote a complete treatise on this subject, using Indo-European technical terms – and in this way introduced or rather popularized the horse in the Near East.

18

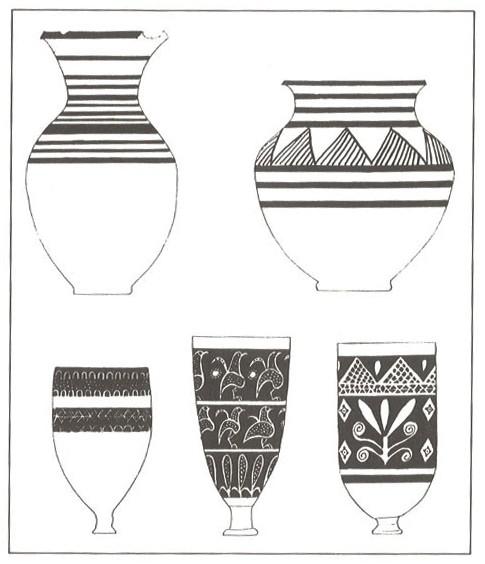

Above: samples of the so-called ‘Khabur pottery’ (16th century

B.C.

), from Chagar Bazar. Below, samples of the so-called ‘Nuzi pottery' (15th century

B.C.

), from Alalah and Nuzi.

After M.E.L. Mallowan

, Iraq,

III (1936) and Sir Leonard Woolley, A Forgotten Kingdom, 1953.

If the contribution of the Hurrians to the civilization of Mesopotamia was negligible, their impact on the less advanced cultures of Syria must have been considerable, though difficult

to define. In any case, their large-scale intrusion in the latter country seems to have started a series of political disturbances and ethnic movements, the effects of which were felt as far away as Egypt.

Syria and Egypt

A line corresponding roughly to the present western and southern borders of the Syrian Republic divides ancient Syria

*

into two parts – the rolling plains of the north and the mountains, hills and deserts of the south – which in prehistory followed a different development. Space does not allow us to describe it, however briefly,

19

but what we think is of interest to our subject is the fact that from very early days the north was wide open to Mesopotamian influences, as it was the link between the Tigris–Euphrates valley, the Mediterranean and, to some extent, Anatolia. If the north, with its hundreds of tells, had been as thoroughly explored as Lebanon or Palestine, the discovery at Ebla of a large and powerful kingdom, dating to the middle of the third millennium

B.C

., and which owed much to the Sumero-Akkadian civilization (see above, page 142) would not have come as a complete surprise. What could not have been expected, however, is that the people of Elba spoke a hitherto unknown Semitic dialect, akin to Akkadian though definitely West-Semitic.

During that time, the south – certainly inhabited by other Semites – looked towards Egypt.

20

Relations between that country and Lebanon or Palestine, already attested in the Pre-Dynastic period, are well documented under the Old Egyptian Kingdom (

c

. 2800 – 2400

B.C.

). This was the time of the great pyramids, and Egypt looked like its monuments: lofty, massive, apparently indestructible. Docile to the orders of Pharaoh – the incarnate god who sat in Memphis – and of his innumerable

officials, toiled a hard-working people and an army of foreign slaves. But if the Nile valley was rich, it lacked an essential material: wood. The mountains of Lebanon, within easy reach, were thick with pine, cypress and cedar forests. Thus a very active trade was established between the two countries to their mutual profit. Byblos (Semitic

Gubla

, Egyptian

Kepen

), the great emporium of timber, became strongly ‘Egyptianized’, and from Byblos Egyptian cultural influence spread along the coast. The relations between the Egyptians and the populations of the Palestinian hinterland, however, were far less friendly. The nomads who haunted the Negeb, in particular, repeatedly attacked the Egyptian copper mines in the Sinai peninsula and on occasion raided the Nile delta, obliging the Pharaohs to retaliate and even to fortify their eastern border. The downfall of the Old Kingdom left Egypt unprotected, and we know of the large part played by the ‘desert folk’, the ‘Asiatics’, in the three hundred years of semi-anarchy which followed.

The first centuries of the second millennium witnessed the expansion of the Western Semites in Syria as well as in Mesopotamia, as proved by a break between the Early Bronze and Middle Bronze cultures, and by the predominance of West-Semitic names among the population of Syria-Palestine. While Amorite dynasties rose to power in many Mesopotamian towns, northern Syria was divided into several Amorite kingdoms, the most important being those of Iamhad (Aleppo), Karkemish and Qatna. Around the palaces of local rulers large fortified cities were built, and the objects and sculptures discovered in the palace of Iarim-Lim, King of Alalah, for instance, are by no means inferior in quality to those found in the contemporary palace of Zimri-Lim, King of Mari. We have already seen that the archives of Mari offer ample proof of intimate and sometimes friendly contacts between Mesopotamia and Syria, and indeed, one cannot escape the impression of a vast community of Amorite states stretching from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf. At the same time commercial relations between Syria and Crete were intensified. A colony of Minoan traders established

itself in the port of Ugarit (Ras Shamra)

21

and the exquisite Kamares crockery found its way to the tables of Syrian monarchs. Egypt, then in the full revival of its Middle Kingdom (2160 – 1660

B.C

.), renewed and consolidated the ties which attached it to the Lebanese coast and endeavoured to counter the growing Hurrian influence in northern Syria by lavishing presents on the Amorite courts. This, at any rate, is a possible explanation for the vases, jewels and royal statues sent to Byblos, Beirut, Ugarit, Qatna and Neirab (near Aleppo) by the Pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty.

22

The region to the south of the Lebanon presents us with a very different picture. Much poorer than northern Syria and less open to foreign influences, Palestine in the Middle Bronze Age (2000 – 1600

B.C

.) was a politically divided and unstable country ‘in the throes of tribal upheaval’

23

where the Egyptians themselves had no authority and apparently little desire to extend their political and economic ascendancy. The arrival among those restless tribes of Abraham and his family – an event whose after-effects are still acutely felt in the Near East – must have passed almost unnoticed. Small clans or large tribes constantly travelled in antiquity from one side to the other of the Syrian desert, and there is no reason to doubt the reality of Abraham's migration from Ur to Hebron

via

Harran as described in

Genesis

xi. 31. A comparison between the biblical account and the archaeological and textual material in our possession suggests that this move must have taken place ‘about 1850

B.C.

, or a little later’,

24

perhaps as the result of the difficult conditions which prevailed then in southern Iraq, torn apart between Isin and Larsa. The historical character of the Patriarchal period was further reinforced – so it was thought some years ago – by the mention in cuneiform and hieroglyphic texts dating mostly from the fifteenth and fourteenth centuries

B.C

. of a category of people, generally grouped in bellicose bands, called

habirû

(or ‘

apiru

in Egyptian), a name which sounded remarkably like biblical ‘

Ibri

, the Hebrews. There was at last the long-awaited appearance in non-hebraical sources of Abraham's kin!

Unfortunately, recent and thorough reappraisals of these sources have shown beyond any doubt that the Habiru have nothing in common with the Hebrews but a similitude of name. They were neither a people nor a tribe, but a class of society made up of refugees, of ‘displaced persons’ as we would now say, who frequently turned into outlaws.

25

In about 1720

B.C.

the Palestinian chieftains, whose turbulence and hostile attitude had already worried the last Pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty, succeeded in invading Egypt, which they governed for nearly one hundred and fifty years. They are known as Hyksôs, the Greek form of the Egyptian name

hiqkhase

, ‘chieftain of a foreign hill-country’. Although they never occupied more than the Nile delta, their influence on the warfare, the arts and even the language of that country was considerable. In the end, however, the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty overthrew the Hyksôs, chasing them up to the gates of Gaza, and with this exploit opens what we call the New Empire (1580 – 1100

B.C.

), undoubtedly the most glorious period in the history of ancient Egypt. By contrast, Mesopotamia fell, at about the same time (1595

B.C.

into the hands of other foreigners, the Kassites, and entered into a long period of political lethargy.