French Literature: A Very Short Introduction (13 page)

Read French Literature: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: John D. Lyons

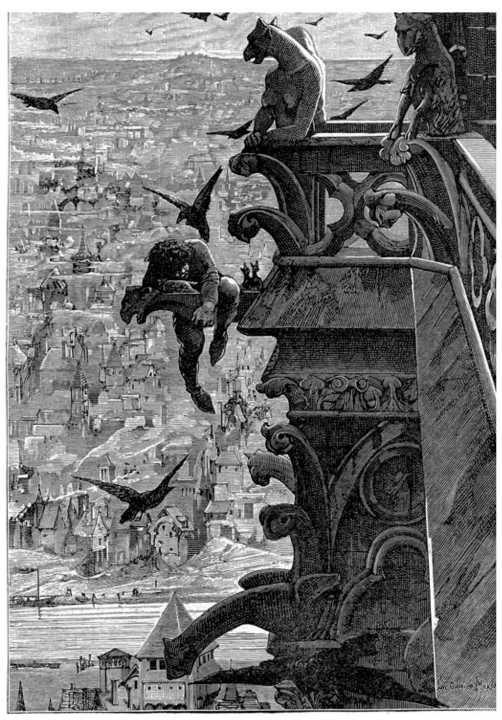

9. Engraving by Luc-Olivier Merson (1881) inspired by Victor Hugo's

novel Notre Dame de Paris (1831)

Heroes of the grotesque

The link between the grotesque and the medieval appears in

Hugo's Notre Dame de Paris (1831, fourteen years before the

restoration of the crumbling monument was undertaken, in

part because of the impact of Hugo's work) - a novel best known

in English as The Hunchback ofNotre Dame. Although Hugo

disapproved of the English title, because for him the cathedral

itself was the central character, the association of a deformed

body and a generous spirit in the fictive late 15th-century

bell-ringer Quasimodo provides one example of the doubleness

that the author so prized. The hunchback first appears in the

novel when a festive crowd decides to elect its own `pope of

fools' on the basis of the ugliest grimace. The contestants in turn

poke their faces through a broken circular window in a chapel

wall - thus, in effect, uniting the grimacing face with the stone

to suggest a gothic grotesque or gargoyle. Finally, a head appears

that is universally acclaimed. It is perfect: `But then surprise and

admiration reached their pinnacle. The grimace was his face.

Or rather, his whole body was a grimace' (Mais c'est alors que la

surpise et l'admiration furent a leur comble. La grimace etait son

visage. On plutot toute sa personne etait une grimace). This is

Quasimodo, who is both metonymically and metaphorically tied

to the cathedral itself: he is constantly present in the church, and

he is also similar to the building in its gothic aesthetic.

But the best-known dramatic example of this grotesque doubleness

is Lorenzaccio, Alfred de Musset's drama published seven

years after Hugo's preface to Cromwell. Neither Cromwell nor

Lorenzaccio were ever performed during their authors' lifetimes,

both were too incendiary by the standards of censorship of the

time, and both were, in their published form, considered impossible

to stage - Musset's play seems to require from sixty to a hundred

actors and extras. Musset based Lorenzaccio in part on a text by

his lover George Sand (Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin, Baroness

Dudevant), a scene historique entitled Une conspiration en 1537.

Musset's work concentrates on the main hero's moral character,

which at first seems, both to the audience and to almost all of his

contemporaries within the play, to be entirely vicious. Completely

absorbed in the pleasures of drink and sex, Lorenzo serves as

procurer for his master and cousin, Alexandre, Duke of Florence,

for whom he quickly and skilfully acquires the sexual services of the

women of the city, by threats, promises, and money. A coward, he

never carries a sword and is called by the Duke himself afemmelette

(a `womanling') after Lorenzo faints when challenged to a duel.

As the scenes unfold, Lorenzaccio (the contemptuous form of the

name that the Florentines have given him) seems entirely to merit

everyone's scorn as bully, spy, toady, and coward. But then it appears

that Lorenzaccio's character has been deliberately assumed for the

purpose of killing Alexandre - in this way, Lorenzo would simply be

a highly successful actor, concealing a unified and noble self. What

makes Lorenzaccio fascinating to Musset, however, is something

much darker: Lorenzo, the originally pure, studious, idealistic

scholar of ancient Rome, who modelled himself on Lucius Junius

Brutus, the killer of Tarquin, is not merely feigning to be vicious but

rather he has really become Lorenzaccio.

Hugo's concept of a double man, both hideous and sublime, is

realized in Musset's hero, who has really become addicted to the

brutally licentious life while still aspiring to a heroic gesture of

political and personal purity. We are led to suppose that what we

have seen of Lorenzaccio in the first scene is not simply a feint but

a true expression of his own desires:

What is more curious for the connoisseur than to debauch an

infant? To see in a child of fifteen the future slut; to study, seed,

insinuate the thread of vice under the guise of a fatherly friend...

(Quoi de plus curieux pour le connaisseur que la debauche a la

mamelle? Voir dans une enfant de quinze ans la rouee a venir;

etudier, ensemencer, infiltrer paternellement le felon mysterieux du

vice dans le conseil dun ami...)

Disseminating corruption throughout the families of Florence

as within himself, Lorenzaccio has become such a cynic, or such

a realist, in regard to human nature that his intention to follow

through on his solitary plot to kill Alexandre has no connection

whatever with the anti-tyrannical agitation among certain

groups of Florentine families. In representing the character of

the Florentines - and through them, no doubt, his 19th-century

contemporaries - Musset shows that those who are outwardly

`noble' and quick to defend their honour are ineffectual.

Lorenzaccio, outwardly despicable, manages to achieve the death

of Duke Alexandre, though this really changes nothing. At the

end of the play, as at the beginning, the Florentines complain and

conspire, and life goes on as always.

The provincial life

The exasperated sense that heroic striving is vain, and that

the coarse, materialistic, conservative common sense of the

bourgeoisie will always triumph over those who seek something

more out of life often was embodied in the contrast between

fast-changing, fashionable Paris and the stodgy, rustic, and boring

provincial life. Balzac's immense collection of novels, which, in the

course of its evolution, he decided to call The Human Comedy (La

Comedie Humaine) is divided into various series and subseries

that reflect the importance of the Paris - province distinction,

such as the `Scenes of the life of the provinces' (Scenes de la vie de

province), the `Scenes of Parisian life', and `Scenes of country life'.

Yet the greatest hero to strive against the prison of the provincial

life is Emma Bovary, the protagonist of Gustave Flaubert's novel

Madame Bovary.

When it first appeared as a serial in 1856 in the Revue de Paris,

the work had the highly significant original title, Madame Bovary,

moeurs de province. For Emma, a woman more intelligent than any

of those around her, though with only a convent education, the most

powerful magic is contained in the words, `They do it in Paris!' (Cela se fait a Paris!), five words that suffice to propel her into the arms

of her second lover. Paris is for her the ultimate place of dreams,

though the dimension of place is insufficient without the figure of

an ideal role or persona. Flaubert's novel is full of representations

of the effect of representation, fictions that propel actions. Emma

delights in heroines who come to her from stories told by the

nuns, novels, magazines, and even from plates! As a child in the

convent, `they had supper on painted plates that depicted the story

of Mlle de La Valliere' (the young mistress of Louis XIV, who once

fled from the court to a convent). In her remote Norman village,

Emma receives magazines from Paris, and she reads the novels of

George Sand and Balzac. At one point, her mother-in-law tries to

keep her from reading novels - a hint that Emma is a latter-day

Don Quixote, maddened by reading. Her life cycles through fits of

intense energy and striving to make something of herself, followed

by periods of lethargy and sickness. This alternation contrasts with

provincial routine, so regular in its seasonal cycles that it seems

to be unchanged since time immemorial. Though she stands out

from her milieu - and thus permits Flaubert to create a multitude

of picturesque characters with all the acuity of a Dickens - Emma

is neither a person of great intelligence nor refinement. Her

unhappiness illustrates something said in Hugo's Notre Dame de

Paris, A one-eyed man is much more incomplete than a blind one.

He knows what he is missing' (Un borgne est Bien plus incomplet

qu'un aveugle. Il sait cc qui lui manque).

The view of la province conveyed in Flaubert (as in the novels

of Stendhal and Balzac) shows that the cult of nature and of

village life, so dear to followers of Rousseau and Bernardin de

Saint-Pierre, had by mid-century provoked a backlash. There

is nothing uplifting and noble about herding cows in Flaubert's

work, and vistas of fields with flowers do not bring Emma any

consolation. In fact, through Emma's cliche-ridden imagination,

Flaubert parodies the romantic notion of an idyllic escape to the

countryside when Emma fantasizes eloping with Rodolphe to `a

village of fishermen, where brown nets were drying in the wind, along a cliff with little huts. That is where they would settle down

to live: they would have a low house with a flat roof, in the shade

of a palm tree, at the end of a gulf, on the seaside'. This is both

particularly comic and also very sad, in that Emma, who lives in

the country, has internalized the fantasies of the city dweller she

aspires to be.

Since Emma is a reader of Flaubert's friend and fellow novelist

George Sand, it is difficult to resist comparing the character of

Emma to the heroine of Sand's earlier work Consuelo (1842),

a vast historical novel, set in the 18th century, that is almost

picaresque in its structure though not in its tone. Consuelo

follows the life of Consuelo from her impoverished childhood

in Venice to her eventual marriage to the half-mad Bohemian

(Czech) aristocrat Albert of Rudolstadt. Point by point, the two

novels are entirely opposite: Emma is trapped in a prosaic French

village, while Consuelo's life is almost a travelogue of the Austro

Hungarian empire; Emma yearns for the aristocratic life and

for the sophistication of the city and the theatre, while Consuelo

spends a good deal of time fleeing all of these things. The life

around Emma seems intensely boring but she tries to infuse it

with excitement, while Consuelo's life is fully Romantic in the

atmosphere and adventures that take place in medieval castles

with subterranean passageways and gloomy forests. But most of

all, the temperament of each heroine is directly opposed. Consuelo

is goodness itself, always patient, generous, resourceful, caring for

others, indifferent to wealth and prestige, and with no need for

exotic escape.

Urban exiles

Any where out of the world', was Charles Baudelaire's diagnosis

of human aspirations, so well represented by Emma Bovary

and so foreign to Consuelo. The expression, in English, was the

title of one of the prose poems in the volume Le Spleen de Paris

(1869). In Any where out of the world', he evokes the power of the eternal `elsewhere': `This life is a hospital where each patient is

obsessed with the desire to change beds'. This interest in what is

happening in the other parts of the world/hospital is a key to the

fascinating paradox that Flaubert, like Balzac, Sand, Stendhal,

and others, could entertain sophisticated readers with stories of

the supposedly stifling provincials, who, in turn, are shown to

spend their time longing for Paris (or longing for village life as if

they were Parisians). What could Parisians like Baudelaire find to

interest them in the life of an unhappy provincial housewife?

Baudelaire was one of the many admiring readers of Flaubert's

novel. In his review essay on Madame Bovary - which appeared

several months after the trial that acquitted Flaubert for outrage

to public and religious morality - Baudelaire described the novel

as the triumph of the power of writing, a power so great that it

scarcely needed a subject. Baudelaire either knew or intuited a

famous formulation that Flaubert used in a letter to his lover Louise

Colet five years earlier, saying that his dream was someday to write

`a book about nothing... that would have almost no subject or at

least where the subject would be almost invisible' (1852). Baudelaire

found in Madame Bovary the triumph of this artistic challenge: to

take the most banal subject, adultery, in the place where stupidity

and intolerance reign, la province, and to create a heroine who

faces this `total absence of genius' in a masculine way. This heroine,

Madame Bovary herself, `is very sublime in her kind, in her small

milieu and facing her small horizon. Baudelaire, in praising both

Flaubert's novel and its heroine, seems at times to identify with her,

despite the radical difference in places.

The quintessential Parisian poet, Baudelaire is almost

unimaginable elsewhere, but this is not to say that he sings

the praises of Paris. Having absorbed Hugo's teaching about

the grotesque and about human doubleness, Baudelaire was

fascinated by the ugly and by the sublime, by all that was

unpredictable and out of place. Perfectly Parisian, Baudelaire, as

both poet and as subject of his poetry, cultivated his sense of being in the wrong place as much as Emma Bovary did hers. He wrote

of Emma that in her convent school she made for herself a'God of

the future and of chance', and one of the great values of the capital

for Baudelaire was its capacity to produce random encounters that

generated lyrical fusions.