French Literature: A Very Short Introduction (16 page)

Read French Literature: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: John D. Lyons

The heritage of Mallarme

Proust's contemporary Paul Valery (1871-1945) was of a radically

different aesthetic temperament. In contrast to the former's

lengthy novel with its notoriously long and involved sentences

(some spreading over several pages), Valery's texts, both in

prose and verse, are all very spare. Among the more unusual

protagonists of French literature is his Monsieur Teste, the hero

of a series of texts - one could call them prose poems or essays -

in which Valery explores his intellect in the form of an alter-ego,

whose name evokes both `head' (tete, or teste in older French)

and `text' (texte). Likewise in his verse poems, Valery represents

a self, a moi, that borders on the metaphysical. The closest heir

of Mallarme, and the last great Symbolist poet, Valery's single

greatest poetic achievement is The Graveyard by the Sea (Le

Cimetiere marin,1920). Like much contemporary painting (one

might think of Kandinsky), this verse poem in 24 stanzas evokes

an event or scene that is then distilled to its essence, so much so

that the physical incident is scarcely glimpsed. In The Graveyard

by the Sea, the poet seems to describe an epiphany that he has

during hours of thought while looking out at the Mediterranean

from a cemetery. The question that he ponders is the relation

between body, mind, and time (themes that run throughout the

Teste texts also), with a concluding acceptance of the body and

the demands and pleasures of physical life. More immediately

accessible is the brief poem `The Footsteps' (Les Pas), published a

year after The Graveyard.

Les Pas

The Footsteps

Translated by David Paul

`The Footsteps' gives a very good idea of the way Valery plays on the

threshold of the physical and the metaphysical in much of his poetry.

The poem is addressed to a pure person'. Is this a woman or a spirit?

Is the `divine shadow' literally divine, or is this hyperbole? Are the

footsteps meant to be actual footsteps, or are they the metric feet of

the poem itself? Or are the pas the poet's heartbeats (he says that his

heart is nothing other than these pas), which he can hear because all

is silent around him? And when those pas cease, it seems that the

poet, as well as the poem, will come to an end. These are the kinds of

questions that Valery's poems provoke and that create opportunities

for patient meditation, which for Valery was a distinct superiority of

poetry over the 19th-century novel.

Surrealism

Valery's acquaintance Andre Breton also reacted against the novel

as genre, and Nadja (1928; revised edition 1962) is one alternative

that he proposed. Breton's work is significant because of his role as

leader of the Surrealists, a movement that reflected the continentwide hunger for something new to replace both 19th-century

literature and art and also the social order that had led to the

butchery of the First World War. French Surrealism appears in

the context of such other movements as Italian Futurism (already

launched before the war but with its major impact in the decades

thereafter), British Vorticism, Soviet Constructivism, the German

Bauhaus, and Swiss and French Dadaism. Andre Breton was the

author of the two Surrealist Manifestos (in 1924 and in 1929), thus becoming the public leader of the most significant of these

movements (by `movement' here is meant a group of writers

who designate themselves as such and advocate a set of aesthetic

and social doctrines). Breton advocated giving priority to the

imaginative life and considered the `real' life as most people know

it to be only a pale reflection of the much more real (surreel,

`above real') life that was to be achieved upon the overthrow of

narrowly rationalist forms of thought and the rejection of the

limited options of adult life. In such a limited, ordinary person,

dominated by practical concerns:

All his gestures will be paltry, all his ideas narrow. He will only

consider, in what happens to him and can happen to him, only

the links to a mass of similar events, events in which he did not

participate, missed events.

(Toes ses gestes manqueront d'ampleur; toutes ses idees, d'envergure.

Il ne se representera, de ce qui lui arrive et pent lui arriver, que

ce qui relie cet evenment a unefoule d'evenements semblables,

evenements auxquels it n'a pas pris part, evenements manques.)

The life of the imagination, which most of us have lost, is cruelly

rich in possibilities. In an apostrophe, Breton exclaims, `Dear

imagination, what I love above all about you is that you do not

forgive' (Chere imagination, ce que j aime surtout en toi, c'est que

to ne pardonnes pas). The world of imagination, for Breton, is not

in the elaborate and carefully wrought creations of the novelists

and poets of the tradition but, instead, in the everyday world that

surrounds us without our noticing it. Breton was an early and

enthusiastic reader of Sigmund Freud (as one can see from the

term `missed events' - coined on the model of the French term

for what we call the lapsus or `Freudian slip', an acte manque), an

admirer of Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi (1896) and of Lautreamont's

Chants de Maldoror (printed in 1868 but little known until the

1920s), and he promoted the concept of `automatic writing'

(ecriture automatique), first practised in the collection of poetic prose Magnetic Fields (Les Champs magnetiques, 1919, with

Philippe Soupault), as a way of breaking out of traditional forms

and rationalist thinking.

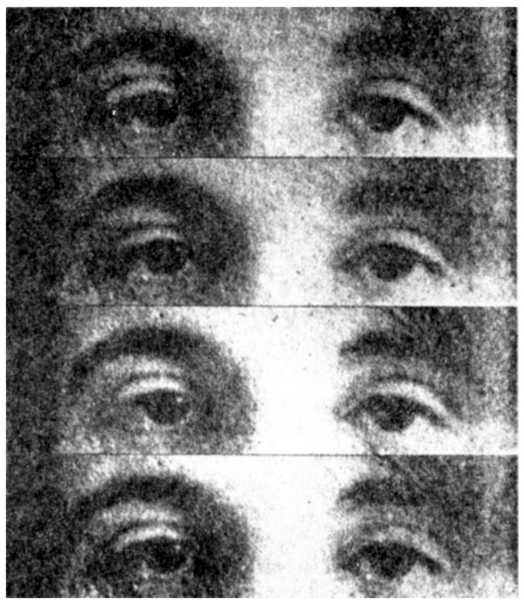

13. `Les yeux de fougere', photographic montage illustration for Andre

Breton's Nadja (1928)