French Literature: A Very Short Introduction (17 page)

Read French Literature: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: John D. Lyons

Given Breton's preference for writing that eschewed any form

of premeditation, moral censorship, and respect of traditional

genres, it is not surprising that he assigned great weight to the

creative role of chance in life. This is illustrated in his text Nadja, which is sometimes called a'novel', though Breton fulminated

against the tradition of the novel and stated that it was simply

the record of real events, centred on his chance encounter with

a young woman who called herself Nadja (though she made it

clear that this was not her real name). He perceived in Nadja

various parapsychological powers, and in answer to his question

`Who are you?', she answers, `I am the wandering soul' (Je suis

l'&me errante). He meets her several times, often by chance, and

as they wander through Paris, each place becomes heavy with

half-explained significance, suggesting that Nadja, at least, has

had a previous existence in some of these locations. They dine

in the Place Dauphine and later find themselves, by chance, in a

cafe named'Le Dauphin'; Breton explains that he had often been

identified with the sea-mammal of the same name, the dolphin.

Breton's respect for the reality of these Parisian places can be

seen in the 48 photographs that are integrated into the text,

some of them reproducing drawings made by Nadja, but most

representing locations such as the Hotel des Grands Hommes in

the Place du Pantheon, Place Dauphine, the Humanite bookstore,

the Saint-Ouen flea market, and so forth. These photographs

ostensibly serve to avoid the lengthy descriptions that are so

much a part of 19th-century realist and naturalist novels, but,

since Breton does also describe things and people in words, they

seem to have another purpose, or at least the effect, of preserving

objects that have an almost talismanic importance for the author.

Breton's slim volume - Nadja is closer in size to a pamphlet than

to most novels - does have at least one thing in common with

Proust's sprawling work. Both authors consider the everyday

world to be a source of great fascination and continue the progress

of an ever greater inclusiveness in what can be deemed worthy of

description and narration. For Proust, asparagus, diesel exhaust,

and homosexual brothels figure alongside gothic churches and

chamber music, while Breton found flea markets, film serials,

and advertisements important to include in his text. Even more

important is the role these authors give to involuntary mental processes in aesthetic creation. In a celebrated passage ofA la

recherche du temps perdu, Proust's narrator Marcel attributes

the rediscovery of the events of childhood to the unpremeditated

flash of memory that occurs upon tasting a madeleine dipped

in a cup of linden tea. This aesthetic of memoire involontaire is

comparable to Breton's intention, as he stated it in Nadja, to tell

of his life:

to the extent that it is subject to chance events, from the smallest to

the greatest, where reacting against my ordinary idea of existence,

life leads me into an almost-forbidden world, the world of sudden

connections, petrifying coincidences, reflexes heading off any other

mental activity...

An innovative novel from the right

Not all great shifts in writing come out of manifestos and selfproclaimed movements. In terms of prose style, Journey to the End

of Night (Voyage an bout de la nuit) by Louis-Ferdinand Celine

(1894-1961, born Louis-Ferdinand Destouches) had great impact

on the diction of novels in the decades following its publication

in 1932. And in addition to its influence on style, it contributed

to the deflation of the protagonist's claim to the status of `hero' in

the noble sense. In this first-person novel, which begins with the

First World War, the tough-talking, acerbic, working-class young

narrator, Ferdinand Bardamu (the surname matches the author's

and will be the name of the protagonist in Celine's subsequent

novel, Death on the Installment Plan (La mort a credit, 1936) ),

quickly decides that the war is a pointless butchery and gets

himself hospitalized for mental illness, essentially for fear. He is,

in short, anything but heroic, since the examples of heroism he

sees around him seem to spring from lack of imagination or simple

stupidity. Finding himself in a military hospital where the director's

therapeutic idea is to infuse his patients with patriotic sentiments,

Bardamu adapts by feigning compliance and even tells stories that

become the basis for the recital of his `heroic' adventures at the Comedie Francaise. Wandering from Flanders to Paris, and then to

West Africa, and from there to the United States, and finally back

to Paris, where he becomes a medical doctor, Bardamu is a kind

of Candide without the burden of an imposed philosophy. In fact,

he is immune to almost every grand scheme of values, a precursor

to the literature of the `absurd' that became a recognized trend

twenty years later. He serves, like Voltaire's character, as a critical

lens through which to denounce American capitalism and the

French military and colonial classes, and literature itself as vehicle

of heroism. There is something Pangloss-like about the psychiatrist

crowing about the recognition his method has received -'I say that

it is admirable that in this hospital that I direct has been formed

under our very eyes, unforgettably, one of these sublime creative

collaborations between the Poet and one of our heroes' (Je declare

admirable que dans cet hopital queje dirige, it vienne se former

sous nos yeux, inoubliablement, une de ces sublimes collaborations

creatrices entre le Poete et l'un de nos heros!) - but Bardamu, who,

after all, is narrator of this story, is the very first to see through

all this hokum. Celine's narrator's corrosive, wordplay-filled

descriptions achieve their goal of demystification by drowning the

grandiose in the trivial or gross. Manhattan banks appear to him as

hushed churches in which the tellers' windows are like the grills of

confessionals, and only a few paragraphs later Bardamu describes

the efforts of `rectal workers' (travailleurs rectaux) in a public

toilet.

Celine's use of slang and of the rhythms of popular, workingclass speech are matched with a kind of narrow-focus narrative

sequencing that keeps Bardamu's attention fixed on small

details, while provoking the reader to extract from all of this the

ideological significance of this additive critique. In various ways,

Celine's innovations had a strong impact both on his younger

contemporaries, like Albert Camus (in LEtranger), and on much

later writers such as Marie Darrieussecq (in Truismes). The huge

and lasting fame of Journey to the End ofNight has not been

diminished by Celine's anti-Semitism and subsequent ties to the pro-Nazi Vichy regime (he was, after the war, declared a'national

disgrace'). However, the populist hero Bardamu, who had declared

that `the war was everything we didn't understand' (la guerre en

somme c'etait tout ce qu'on ne comprenaitpas), has remained

much more alive for the reading public than the contemporary

anti-war heroes of another First World War novel, Roger Martin

du Gard's LEte 1914 (1936, part of the longer work Les Thibault,

1922-40), for which Martin du Gard won the Nobel Prize for

Literature in 1937. Perhaps, besides the inventiveness and the

biting dark humour of Celine's work, this enduring success among

anti-war novels is due to Bardamu's dead-pan cynicism, which

seems closer to common perceptions of reality than the idealism

of Martin du Gard's idealistic pacifist Jacques Thibault.

The Second World War and the camps

Although Celine continued to write after the Second World

War, his fame depends essentially on Voyage an bout de la nuit

and La mort a credit, because during and after the war, Albert

Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre began to occupy some of the same

terrain of populist critique and to provide coherent philosophical

contextualization for the scepticism and anger that rolled so

unpredictably through Celine's work. The war itself, and the

German camps, ended the lives of many authors and changed

the lives of others. It helped to form lasting institutions like the

publishing house Minuit ('Midnight'), which had published works

clandestinely during the war before becoming a major post-war

press. The war ended much that was playful and experimental in

the entre-deux-guerres period, and Robert Desnos (1900-45, died

of typhus in Theresienstadt) is probably the best example. Editor

of the review La Revolution Surrealiste from 1924 to 1929, Desnos

published abundantly, drawing on the popular culture of Paris and

on pulp crime serials such as FantBmas.

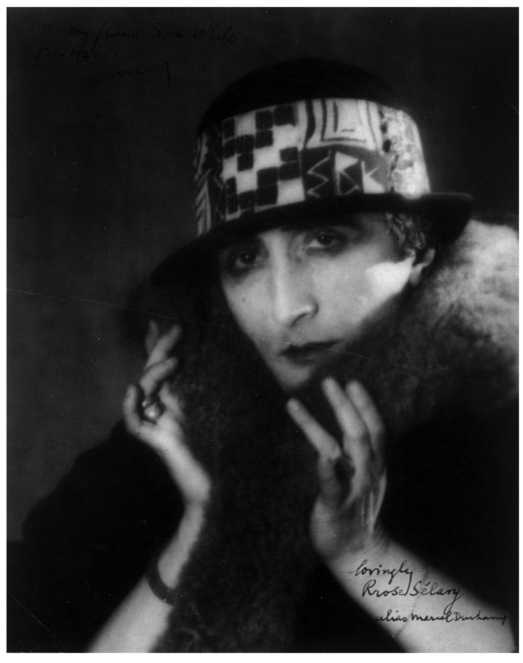

An illustration of the way ideas circulated as jokes within

Surrealist circles is the character Rrose Selavy, who appears, among other places, in Desnos's 1939 book Rrose Se'lavy:

oculisme de precision, poils et coups de pieds en toes genres

(Precision Oculism, Complete Line of Whiskers and Kicks). It

was the multimedia artist Marcel Duchamp who created `Rrose

Selavy' in 1920 as an alter-ego. Duchamp was photographed

in drag as `Rrose' by Man Ray, and then Desnos made `her' a character threaded through some of his poems, even as late

as June 1944, just a year before his death. In `Springtime'

(Printemps, June 1944), we see the formerly playful figure now

remembered as belonging to the imagination of a former time, or

of a time that may come again later, after the poet's death in the

theatre of war.

14. Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Selavy, c. 1920-1, in a photograph by

Man Ray

Printemps