French Literature: A Very Short Introduction (14 page)

Read French Literature: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: John D. Lyons

It is understandable that the metropolis in mid-century should

offer freedom and opportunity on a quite different scale from

any other city in France, for it was growing explosively. In 1801,

Paris had had virtually the same population as at the end of the

17th century, roughly half a million inhabitants in an area of

less than 14 square kilometres. By the end of the century, the

population quintupled, and Paris had annexed nearby towns and

villages so that the urban area was eight times larger. Such an

environment favours the `God of chance' Baudelaire attributed

to Emma Bovary, and he seized for himself a poetic persona well

adapted to this moment, that of the stroller (le flaneur), a role

that he describes in an essay on the painter Constantin Guys, `The

Painter of Modern Life': `For the perfect stroller, for the passionate

observer, it is an immense pleasure to dwell in the multitude, in

the undulating, in movement, in the fleeting, and the infinite'.

The sonnet `To a Woman Passing By' (A unepassante, in Les

Fleurs du mal [Flowers of Evil]) illustrates the intensity and the

chance nature of the encounters that the poet-stroller prizes in the

immense, fast-moving, modern city. The two quatrains, with no

addressee, describe a crowded street scene and then the vision of a

striking woman. The tercets start by evoking the woman's glance,

and then the poet addresses the woman directly. The lightninglike strike of the glance turns the poet's thoughts forward from

this encounter to the improbability of future encounters, and

shifts the sonnet into a thematic well known to Emma Bovary and

her readers: the longed-for elsewhere and another time, when love

is fulfilled. The single italicized word,jamais (never) - Baudelaire

almost never used italics - stresses the other-worldly character

of this time, which may not come in this life. The woman, who is

in mourning, may indeed be Death, but she may also be simply a woman in the crowd whose ephemeral image nourishes the poet's

imagination and to whom the poet attributes an equal role in this

mental exchange. The very title of the poem suggests extremes,

the fullness of life in a city in which people move rapidly and pass

one another (as they do not in a village) and also the eventual

absence of movement of someone who has passed beyond life -

life and death themselves telescoped into the antithesis of a

lighting flash followed by darkness.

A variant of Hugo's double man, the stroller is exquisitely attuned

to time, and especially to the vanished past and to the dissonance of near misses. He lives vividly both in the Parisian present

and in the past and the elsewhere. In `The Swan' (Le Cygne,

dedicated to Victor Hugo, 1860), Baudelaire builds his poem

around another chance encounter in a Paris undergoing the

colossal transformations that Haussmann carried out between

1853 and 1870 and that created the city of wide boulevards and

standardized building heights that we know today. In the process,

most of medieval Paris disappeared, thus endowing the vestiges

of the Middle Ages with a new, nostalgic, value.

A une passante

To a Woman Passing By

In `The Swan', Baudelaire creates a deft mosaic of different

moments, especially three: the present, in which he is crossing the

newly constructed Place du Carrousel between the Tuileries and

the Louvre; a past moment when there had been a menagerie in

that place; and the imagined moment in Greek antiquity when

the Trojan prince Hector's widow Andromache, become the

slave of Pyrrhus, bends over the cenotaph of her heroic husband.

Translated by Geoffrey Wagner, Selected Poems of

Charles Baudelaire (New York: Grove Press, 1974)

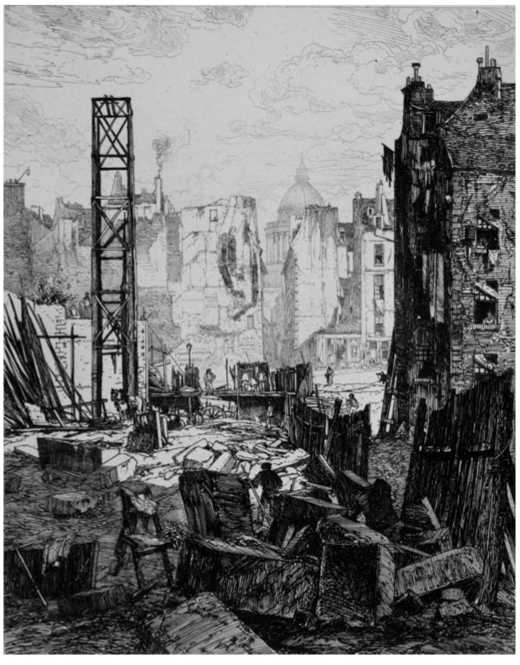

10. Maxime Lalanne (1827-86), `Demolition work for the construction

of the Boulevard Saint-Germain, a scene from Haussmann's renovations

of Paris

Baudelaire assembles these moments along the thematic axis of

absence: in crossing the Carrousel, he sees that the menagerie is

no longer there. In that menagerie, a swan had escaped from its

cage, and vainly sought water from the dry pavement. The poet

imagines the swan remembering the lost lake of its youth and then imagines Andromache remembering Hector. The last three

quatrains of the poem evoke a myriad of others who have lost

something, and specifically those who have lost a place, like the

`emaciated and tubercular Negress ... seeking... the missing palm

trees of proud Africa'. The stroller is thus the guise in which the

city poet can multiply his experience of narrative characters, for he

identifies himself with each in turn: Andromache, the swan, the

African woman, and perhaps even with the dying hero of the Song

of Roland: An old memory blows a horn with full force'.