French Literature: A Very Short Introduction (15 page)

Read French Literature: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: John D. Lyons

The endless change that seemed to Baudelaire to be the only

constant of Paris accelerated a decade after Le Cygne. The FrancoPrussian War of 1870-1 ended the Second Empire and brought

the insurrection known as the Paris Commune and its bloody

suppression. Paris almost tripled its surface area in the second

half of the century, and the continued development of the rail

network centred on the capital brought more workers.

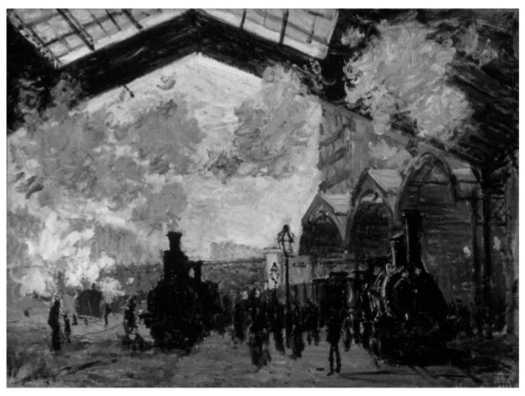

it. Claude Monet, La Gare Saint-Lazare (1877)

One side of this change is reflected in the naturalist novels

of Emile Zola (1840-1902) with their attention to the gritty

underside of this prosperous period, the heyday of the French

colonial empire. These include LAssommoir (1877) and La Bete

humaine (1890), both about the ravages of alcoholism in workingclass families. But in reaction to naturalism in the novel and

theatre came Symbolism, which found in Baudelaire its harbinger

and in Stephane Mallarme its greatest exponent. Much of his

poetry, in appearance frivolous and occasional (for instance, a

series on women's fans, on a coiffure, etc.), concerns death and

memorialization, particularly monuments to poets. With Ronsard

and Hugo, Mallarme is probably the poet who most vigorously

championed the power of language itself to challenge death.

Mallarme's protagonists are therefore most often poets, celebrated

in a series of sonnet `tombs' such as Le Tombeau d'Edgar Poe

(1876), but in time Mallarme reached the highest point of

abstraction with a protagonist named, simply, Igitur (Latin,

`therefore') in a posthumous prose text dating from around 1870,

Igitur, ou lafolie d'Elbehnon. The hero finishes in the tomb after

challenging Nothingness with a roll of the dice: `The character,

who, believing in the existence of the Absolute alone, imagines

himself everywhere in a dream [...] finds action unnecessary' (Le

personnage qui, croyant a l'existence du seulAbsolu, s'imagine

etre partout dans un rive [. ..] trouve l'acte inutile). This text may

be the earliest form of the great hermetic poem that Mallarme

published almost thirty years later, in which we seem to encounter

once again Igitur's roll of the dice: A Roll ofDice Will Never

Abolish Chance (Un coup de des jamais n'abolira le hasard, 1897).

In its graphic disposition, apparently spattered across the page

in different fonts and type sizes, this is one of the most inventive

texts in all of French literature, and it was crucially important for

the following century.

12. A page of Stephan Mallarme's poem, Un coup de des jamais

n'abolira le hasard (1897)

The world of Proust's novel

The heady metaphysical aspirations of Mallarme's spare lyric,

which seem at times ready to leave language and the printed

page behind, appear at first to have little in common with the

roman fleuve, the immense, onward-streaming novel that marks

the emphatic beginning of the 20th century, In Search ofLost

Time (A la recherche du temps perdu, 1913-27) by Marcel Proust

(1871-1922). Yet these two authors of the belle epoque (a name

given after the First World War to the preceding period of peace

from the end of the Franco-Prussion War in 1870 until 1914)

have in common an intellectual adventurousness nourished

by the philosophical movements of the time. It is tempting to

consider Proust's novel as a Bildungsroman (or as a variant

thereof, the Kunstlerroman - the education of the artist), but

one in which the usual linearity of that form has yielded to an

extremely complex interplay of moments of experience and later

moments of interpretation. This complexity is augmented by

length, competing editions based on different opinions concerning

the proper use of posthumous material, and different English

translations with different titles. A la recherche du temps perdu,

which in the current French Pleaide edition runs (with extensive

notes) to more than 7,000 pages, is comprised of seven titled

sub-novels. The first of these (published at the author's expense in 1913), Swann's Way (Du cote de chez Swann), contains the further

subsections Combray, Swann in Love (Un amour de Swann),

and Noms de pays: le nom. The last of the seven sub-novels, Le

temps retrouve, was published in 1927, five years after Proust's

death. The novel - A la recherche du temps perdu - in terms of

the chronological range covered stretches from these childhood

memories of Combray, at the earliest, to the post-war Paris scenes

of the last novel in the series, The Past Recaptured (Le temps

retrouve, literally `time refound').

Combray, the very first section, opens with the narrator's

account of going to sleep and waking - the startling first

sentence is `For a long time, I went to bed early' (Longtemps,

je me suis couche de bonne heure). The reader has no way of

knowing who is making this statement - and, in fact, the given

name of the protagonist is mentioned only rarely throughout

the seven narratives that make up the work as a whole - but

it becomes clear very quickly that there is something very

capacious and mysterious about this `I'. Having fallen asleep

while reading, he writes, he would sometimes wake a halfhour later still thinking about the book he was reading. But

these thoughts often took a peculiar form: `it seemed to me

that I was the thing the book was about: a church, a quartet,

the rivalry between Francois I and Charles V' (il me semblait

que j etais moi-meme cc dontparlait l'ouvrage: une eglise, un

quatuor, la rivalite de Francois ler et de Charles-Quint). For

several pages, the narrator pursues this investigation into the

contents of the mind at its awakening, with comments on the

identification of the thinking subject with a series of radically

heterogeneous objects. The fact that the mind does not at first

see them as objects but simply as part of itself is, for the reader,

most striking. The narrator continues by tracing the phases of

disengagement as the thinker rejoins the world of wakefulness

and can no longer understand the dream thoughts that at first

seemed so innocently obvious.

These opening pages of the novel, with the radical questioning

of the boundaries of the self, have roots with a deep hold on the

tradition of French literature. Montaigne, in a famous passage of

the Essais, recounted his experience of returning to consciousness

after a fall in the chapter `On Practice' (De l'exercitation), as did

Rousseau in one of his Reveries of the Solitary Walker (Reveries

du promeneur solitaire). Descartes, in his Discourse on Method

(Discours de la methode, 1637) had also tried stripping the

consciousness of the self back to the simple awareness of being

that precedes any actual knowledge of the qualities of that

thinking self. In Proust's day, this Cartesian questioning had been

given a new currency by the teachings of Franz Brentano and his

two brilliant students, Edmund Husserl and Sigmund Freud. And

Proust was certainly aware of the work of Henri Bergson, whose

writings on the awareness of time have been frequently compared

with Proust's work. Though Proust probably reached his interest

in the phenomenology of the waking self independently, it is hard

to deny that he brought a new vigour and concreteness to the

exploration of consciousness, sensation, and memory.

He also gave a new prominence to childhood. The opening

meditation on going to bed and waking leads into an account of

the bedtime ritual during family summer vacations in Combray.

To distract the child from the anguished separation from his

mother that bedtime entailed, his family would let him project a

magic lantern display onto the walls of his room, where Golo, the

hero of the legendary tale represented by the images, exhibits the

ability to morph himself according to the object on which he is

projected - door knob, curtains, walls: `Gob's body itself... dealt

with any material obstacle, with any bothersome object that it

encountered, by taking it as its skeleton, incorporating it, even

the doorknob' (Le corps de Golo lui-meme... s'arrangeait de tout

obstacle materiel, de tout objet genant qu'il rencontrait en be

prenant comme ossature et en se be rendant interieur, fut-ce be

bouton de la porte...). Thus Marcel's ability, as the adult narrator, to imagine his waking self as a church or as the rivalry between

the king and the emperor is prefigured in the child's experience

of the hero's image in the lantern display as it transcends times

and places in order to be himself. While Freud was, by another

approach, teaching the long-term impact of childhood experience,

Proust knit together childhood and adulthood in this persistence

of narrative patterns and in the ability of people to identify - and

to identify with - the protagonist's role.

This ability appears in the narrator's account of Swann, an adult

friend of young Marcel's family, a Parisian who, like Marcel's

parents, has a country house in Combray. As a child, Marcel

dreads Swann's arrival for dinner parties because this means that

his bedtime ritual will be perturbed, his mother will be occupied

with her duties as hostess. In short, Swann appears as the cause

of the terrible suffering due to the absence of the loved one. As an

adult, however, Marcel sees that Swann would have known better

than anyone what that suffering was like, for he suffered also from

his love for Odette de Crecy. This treatment of Swann is simply

an example of Marcel's characteristic plasticity as narrator - but

also as protagonist - to focus on a wide range of people, of whom

he discovers different aspects as he grows older. The fascination

that appears in the early realization that 'Golo' could be himself

but also a doorknob is the force that gives value to the subsequent

realizations that people, attitudes, actions, and places that at first

seemed entirely distinct and incompatible are, in fact, united. For

instance, the paths in Combray that lead towards Swann's house

(that is, that go du cote de chez Swann) seem at first to be entirely

opposite those that go towards the chateau de Guermantes,

and Swann and the aristocratic Guermantes family seem quite

separate, but they are later shown to be connected. However,

as even his perception of the spatial organization shows, the

narrator's greatest talent is in creating unforgettable people. So

that any reader ofA la recherche du temps perdu is likely to carry

around a mental repertory with characters such as Francoise the cook, Tante Leonie, Baron Charlus, Saint-Loup, Albertine,

Elstir the painter, and so forth. These all flow out of the moi of

the narrator himself, who becomes a super-character and the

repository of the entire world that he recounts. Among the most

moving pages of the novel are in the concluding section, Le temps

retrouve, where he realizes that the past is not gone because it still

lives in him.