Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (150 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

6.76Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

pulmonary embolism

amniotic fluid embolism

haemorrhage (antepartum and postpartum)

pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

septic shock

anaesthetic causes (e.g. high spinal block, intubation difficulties)

cardiac disease

respiratory disease.

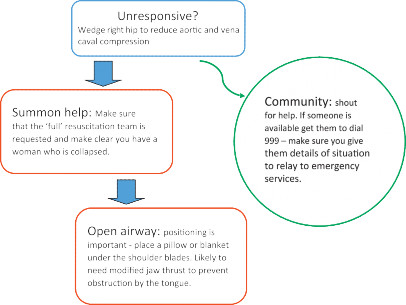

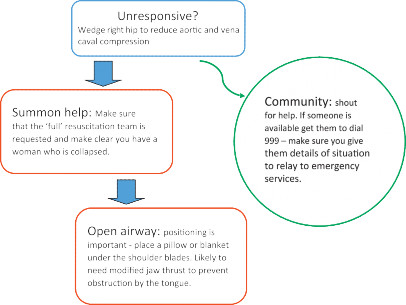

Basic life support

This section utilises the Resuscitation Council (UK) (2010) guidelines; however the normal physi-ological changes associated with pregnancy mean that adaptations to resuscitation procedures have to be made to overcome the problems presented by the altered physiology. The algorithm for basic life support is shown in Figure 16.3, to provide an overview of the process of maternal resuscitation. Early basic life support interventions are the key to the success of resuscitation, but it is important to remember that it is a ‘holding’ intervention to maintain the patient whilst medical personnel and the necessary equipment arrive to instigate advanced life support meas- ures (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010). Just as early basic life support is vital so is early access to advanced life support and it is therefore essential to note the differences in the algorithm for arrests occurring out of hospital (community).

Approach with care

Always assess the area around the woman for potential hazards as an injured rescuer is no use to her. Any obstacles should be moved out of the way and if the floor is wet a sheet or similar can be used to place over the wet area to minimise the risk of slipping. If the woman is in the birthing pool she will need to be lifted out and placed on the floor or bed (this should be done in accordance with patient handling hospital policy).

Shake and shout

Gently shake her shoulders and ask her loudly if she is alright to try and gain a response. If the baby is still in utero, wedge the right hip with a pillow or blanket to reduce pressure on the aorta and inferior vena cava.

Summon help

If she does not respond, then help should be summoned. In hospital this should be done by means of the emergency buzzer, and whoever answers should call the emergency resuscitation team (a full cardiac arrest team plus obstetric personnel should be requested and a neonatal/ paediatric team if the baby is in utero). In the community setting, anyone in the vicinity that can help should be asked to summon an ambulance using 999. It is essential that the person ringing for an ambulance has specific and appropriate information to give to the emergency services.

A

irway

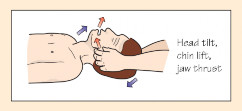

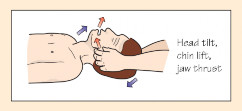

Inspect the mouth for vomit, blood or any other obstruction. Suction can be used to clear the airway, but finger sweeps should only be used if the obstruction can be clearly seen and lifted out. Any action taken in this respect should not take a large amount of time. The airway should be opened by means of a head tilt, chin lift and jaw thrust combined (see Figure 16.2 and Box 16.3). Placing a pillow or blanket under the shoulder blades will assist with opening the airway and being able to visualise the vocal cords during advanced life support.

351

351

352

352

Figure 16.2

Head tilt, chin lift, jaw thrust. Source: Blundell and Harrison 2013, Chapter 13, Station 30, p. 38. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Box 16.3 Airway opening manoeuvres (Figure 16.2) HEAD TILT – CHIN LIFT MANOEUVREPlace a hand on the forehead and tilt the head back gently into a neutral position with the neckslightly extended. Place the fingers (not thumb) of the other hand under the bony part of the lower jaw and lift the mandible upward and outward.

Box 16.3 Airway opening manoeuvres (Figure 16.2) HEAD TILT – CHIN LIFT MANOEUVREPlace a hand on the forehead and tilt the head back gently into a neutral position with the neckslightly extended. Place the fingers (not thumb) of the other hand under the bony part of the lower jaw and lift the mandible upward and outward.

JAW THRUST MANOEUVREPlace two or three fingers under each side of the lower jaw at its angle and lift the jaw upward and outward.

JAW THRUST MANOEUVREPlace two or three fingers under each side of the lower jaw at its angle and lift the jaw upward and outward.

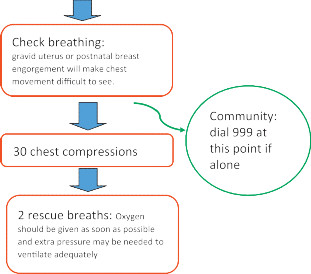

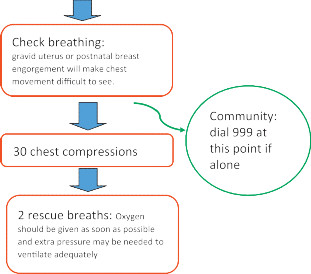

B

reathing

Look, listen and feel for normal breathing.

Basic life support

This section utilises the Resuscitation Council (UK) (2010) guidelines; however the normal physi-ological changes associated with pregnancy mean that adaptations to resuscitation procedures have to be made to overcome the problems presented by the altered physiology. The algorithm for basic life support is shown in Figure 16.3, to provide an overview of the process of maternal resuscitation. Early basic life support interventions are the key to the success of resuscitation, but it is important to remember that it is a ‘holding’ intervention to maintain the patient whilst medical personnel and the necessary equipment arrive to instigate advanced life support meas- ures (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010). Just as early basic life support is vital so is early access to advanced life support and it is therefore essential to note the differences in the algorithm for arrests occurring out of hospital (community).

Approach with care

Always assess the area around the woman for potential hazards as an injured rescuer is no use to her. Any obstacles should be moved out of the way and if the floor is wet a sheet or similar can be used to place over the wet area to minimise the risk of slipping. If the woman is in the birthing pool she will need to be lifted out and placed on the floor or bed (this should be done in accordance with patient handling hospital policy).

Shake and shout

Gently shake her shoulders and ask her loudly if she is alright to try and gain a response. If the baby is still in utero, wedge the right hip with a pillow or blanket to reduce pressure on the aorta and inferior vena cava.

Summon help

If she does not respond, then help should be summoned. In hospital this should be done by means of the emergency buzzer, and whoever answers should call the emergency resuscitation team (a full cardiac arrest team plus obstetric personnel should be requested and a neonatal/ paediatric team if the baby is in utero). In the community setting, anyone in the vicinity that can help should be asked to summon an ambulance using 999. It is essential that the person ringing for an ambulance has specific and appropriate information to give to the emergency services.

A

irway

Inspect the mouth for vomit, blood or any other obstruction. Suction can be used to clear the airway, but finger sweeps should only be used if the obstruction can be clearly seen and lifted out. Any action taken in this respect should not take a large amount of time. The airway should be opened by means of a head tilt, chin lift and jaw thrust combined (see Figure 16.2 and Box 16.3). Placing a pillow or blanket under the shoulder blades will assist with opening the airway and being able to visualise the vocal cords during advanced life support.

351

351 352

352Figure 16.2

Head tilt, chin lift, jaw thrust. Source: Blundell and Harrison 2013, Chapter 13, Station 30, p. 38. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Box 16.3 Airway opening manoeuvres (Figure 16.2) HEAD TILT – CHIN LIFT MANOEUVREPlace a hand on the forehead and tilt the head back gently into a neutral position with the neckslightly extended. Place the fingers (not thumb) of the other hand under the bony part of the lower jaw and lift the mandible upward and outward.

Box 16.3 Airway opening manoeuvres (Figure 16.2) HEAD TILT – CHIN LIFT MANOEUVREPlace a hand on the forehead and tilt the head back gently into a neutral position with the neckslightly extended. Place the fingers (not thumb) of the other hand under the bony part of the lower jaw and lift the mandible upward and outward. JAW THRUST MANOEUVREPlace two or three fingers under each side of the lower jaw at its angle and lift the jaw upward and outward.

JAW THRUST MANOEUVREPlace two or three fingers under each side of the lower jaw at its angle and lift the jaw upward and outward.B

reathing

Look, listen and feel for normal breathing.

Look for chest movement but remember this may be difficult due to splinting of the dia- phragm by the uterus and baby and/or enlargement of the breasts.

Listen for breath sounds.

Feel for air on your cheek.

This assessment should take no longer than 10 seconds.

NOTE: If you are alone in the woman’s home or community setting this is the point at whichyou should summon an urgent paramedic ambulance.

C

hest compressions

Give 30 chest compressions if the woman is not breathing.

Rescue breaths

Use a bag-valve-mask or pocket mask to provide two breaths whilst keeping the airway open (as shown in Box 16.4). Ideally oxygen should be used for the breaths but there should be no delay if it is not available. The procedure should continue with 30 compressions followed by two rescue breaths until help arrives and takes over to provide advanced life support.

Continuing resuscitation

The airway will be secured by means of intubation or the insertion of a laryngeal mask airway. Compressions will be continued but a defibrillator will be attached to monitor any cardiac rhythm and provide shocking where appropriate. There will be a need to cannulate to gain intravenous (IV) access and provide fluid resuscitation with crystalloid or colloid boluses. Drugs such as adrenaline will be given intravenously.

Figure 16.3

Figure 16.3

Basic life support. Source: Based on Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010.

353

353

Box 16.4 Giving chest compressionsPlace the heel of one hand in the centre of woman’s chest (lower half of the sternum). Place the heel of the other hand over the first hand and interlock the fingers. Make sure your hands are placed over the bony sternum not the ribs and that they are not too low (not over the abdomen or bottom end of the sternum).Position yourself vertically above the woman and with your arms straight press down on the sternum. The pressure should aim to move the sternum down by about 5–6 cm; however this is quite hard to do if the woman has been tilted to reduce pressure on major vessels. After the com- pression release all pressure whilst keeping hands in contact with the chest (this allows blood to flow back into the heart).Compression and release should take equal time and should be provided at an approximate rate of 100–120 compressions per minute (the ‘Staying Alive’ rhythm).354

Box 16.4 Giving chest compressionsPlace the heel of one hand in the centre of woman’s chest (lower half of the sternum). Place the heel of the other hand over the first hand and interlock the fingers. Make sure your hands are placed over the bony sternum not the ribs and that they are not too low (not over the abdomen or bottom end of the sternum).Position yourself vertically above the woman and with your arms straight press down on the sternum. The pressure should aim to move the sternum down by about 5–6 cm; however this is quite hard to do if the woman has been tilted to reduce pressure on major vessels. After the com- pression release all pressure whilst keeping hands in contact with the chest (this allows blood to flow back into the heart).Compression and release should take equal time and should be provided at an approximate rate of 100–120 compressions per minute (the ‘Staying Alive’ rhythm).354

For women who are undelivered and over 20 weeks at the time of the arrest, delivery by caesarean section is urgent and is normally performed without moving the woman to the operating theatre.All actions taken must be carefully recorded with accurate times (always use the same clock or watch to avoid inaccuracy).Any family present will need supporting. They may wish to witness the resuscitation attempts and if so should be supported in their need to be present and provided with information about the procedures by a member of the team allocated to look after them.Following a resuscitation event it is normal for staff to feel emotional and support should always be offered. Whilst formal support, often through midwifery supervision, is important, so is peer support. Feelings of inadequacy and questioning are common whether the resuscitation was successful or not and debrief can be helpful in resolving these (Boyle and Yerby 2011).

For women who are undelivered and over 20 weeks at the time of the arrest, delivery by caesarean section is urgent and is normally performed without moving the woman to the operating theatre.All actions taken must be carefully recorded with accurate times (always use the same clock or watch to avoid inaccuracy).Any family present will need supporting. They may wish to witness the resuscitation attempts and if so should be supported in their need to be present and provided with information about the procedures by a member of the team allocated to look after them.Following a resuscitation event it is normal for staff to feel emotional and support should always be offered. Whilst formal support, often through midwifery supervision, is important, so is peer support. Feelings of inadequacy and questioning are common whether the resuscitation was successful or not and debrief can be helpful in resolving these (Boyle and Yerby 2011).

Antepartum haemorrhage

Antepartum haemorrhage (APH) is defined as bleeding from the genital tract from 24 weeksgestation and before the birth of the baby. APH poses significant risk to both mother and baby and is associated in particular with stillbirth and neonatal death. There are two main types of APH: placental abruption (also known as abruptio placentae) and placenta praevia. However there can also be what is known as incidental bleeding from lesions of the genital tract such as cervical polyps, vaginal infection or carcinoma of the cervix. See Box 16.5 for predisposing factors for APH.

Placental abruption

Bleeding occurs when a normally situated placenta separates, either partially or fully, from the uterine wall. The bleeding can be revealed, i.e. obvious bleeding per vaginum (P.V.), concealed where the blood remains trapped between the placenta and the uterus, or mixed where both occur. The degree of separation will determine whether it is categorised as severe, moderate or mild. The cause of separation may not be apparent, but there is an association with sudden decompression as with rupturing membranes where polyhydramnios is present, trauma (road traffic accidents, falls or a blow to the abdomen), hypertensive disease and external cephalic version.

Box 16.5 Predisposing factors for antepartum haemorrhage

Box 16.5 Predisposing factors for antepartum haemorrhage

C

hest compressions

Give 30 chest compressions if the woman is not breathing.

Rescue breaths

Use a bag-valve-mask or pocket mask to provide two breaths whilst keeping the airway open (as shown in Box 16.4). Ideally oxygen should be used for the breaths but there should be no delay if it is not available. The procedure should continue with 30 compressions followed by two rescue breaths until help arrives and takes over to provide advanced life support.

Continuing resuscitation

The airway will be secured by means of intubation or the insertion of a laryngeal mask airway. Compressions will be continued but a defibrillator will be attached to monitor any cardiac rhythm and provide shocking where appropriate. There will be a need to cannulate to gain intravenous (IV) access and provide fluid resuscitation with crystalloid or colloid boluses. Drugs such as adrenaline will be given intravenously.

Figure 16.3

Figure 16.3Basic life support. Source: Based on Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010.

353

353 Box 16.4 Giving chest compressionsPlace the heel of one hand in the centre of woman’s chest (lower half of the sternum). Place the heel of the other hand over the first hand and interlock the fingers. Make sure your hands are placed over the bony sternum not the ribs and that they are not too low (not over the abdomen or bottom end of the sternum).Position yourself vertically above the woman and with your arms straight press down on the sternum. The pressure should aim to move the sternum down by about 5–6 cm; however this is quite hard to do if the woman has been tilted to reduce pressure on major vessels. After the com- pression release all pressure whilst keeping hands in contact with the chest (this allows blood to flow back into the heart).Compression and release should take equal time and should be provided at an approximate rate of 100–120 compressions per minute (the ‘Staying Alive’ rhythm).354

Box 16.4 Giving chest compressionsPlace the heel of one hand in the centre of woman’s chest (lower half of the sternum). Place the heel of the other hand over the first hand and interlock the fingers. Make sure your hands are placed over the bony sternum not the ribs and that they are not too low (not over the abdomen or bottom end of the sternum).Position yourself vertically above the woman and with your arms straight press down on the sternum. The pressure should aim to move the sternum down by about 5–6 cm; however this is quite hard to do if the woman has been tilted to reduce pressure on major vessels. After the com- pression release all pressure whilst keeping hands in contact with the chest (this allows blood to flow back into the heart).Compression and release should take equal time and should be provided at an approximate rate of 100–120 compressions per minute (the ‘Staying Alive’ rhythm).354 For women who are undelivered and over 20 weeks at the time of the arrest, delivery by caesarean section is urgent and is normally performed without moving the woman to the operating theatre.All actions taken must be carefully recorded with accurate times (always use the same clock or watch to avoid inaccuracy).Any family present will need supporting. They may wish to witness the resuscitation attempts and if so should be supported in their need to be present and provided with information about the procedures by a member of the team allocated to look after them.Following a resuscitation event it is normal for staff to feel emotional and support should always be offered. Whilst formal support, often through midwifery supervision, is important, so is peer support. Feelings of inadequacy and questioning are common whether the resuscitation was successful or not and debrief can be helpful in resolving these (Boyle and Yerby 2011).

For women who are undelivered and over 20 weeks at the time of the arrest, delivery by caesarean section is urgent and is normally performed without moving the woman to the operating theatre.All actions taken must be carefully recorded with accurate times (always use the same clock or watch to avoid inaccuracy).Any family present will need supporting. They may wish to witness the resuscitation attempts and if so should be supported in their need to be present and provided with information about the procedures by a member of the team allocated to look after them.Following a resuscitation event it is normal for staff to feel emotional and support should always be offered. Whilst formal support, often through midwifery supervision, is important, so is peer support. Feelings of inadequacy and questioning are common whether the resuscitation was successful or not and debrief can be helpful in resolving these (Boyle and Yerby 2011).Antepartum haemorrhage

Antepartum haemorrhage (APH) is defined as bleeding from the genital tract from 24 weeksgestation and before the birth of the baby. APH poses significant risk to both mother and baby and is associated in particular with stillbirth and neonatal death. There are two main types of APH: placental abruption (also known as abruptio placentae) and placenta praevia. However there can also be what is known as incidental bleeding from lesions of the genital tract such as cervical polyps, vaginal infection or carcinoma of the cervix. See Box 16.5 for predisposing factors for APH.

Placental abruption

Bleeding occurs when a normally situated placenta separates, either partially or fully, from the uterine wall. The bleeding can be revealed, i.e. obvious bleeding per vaginum (P.V.), concealed where the blood remains trapped between the placenta and the uterus, or mixed where both occur. The degree of separation will determine whether it is categorised as severe, moderate or mild. The cause of separation may not be apparent, but there is an association with sudden decompression as with rupturing membranes where polyhydramnios is present, trauma (road traffic accidents, falls or a blow to the abdomen), hypertensive disease and external cephalic version.

Box 16.5 Predisposing factors for antepartum haemorrhage

Box 16.5 Predisposing factors for antepartum haemorrhageOther books

Mum on the Run by Fiona Gibson

The Good Terrorist by Doris Lessing

Choose Yourself! by Altucher, James

The Beautiful American by Jeanne Mackin

Love's Pursuit by Siri Mitchell

The Married Man by Edmund White

The Cold Hand of Malice by Frank Smith

The Wedding by Buchanan, Lexi

When Will the Dead Lady Sing? by Sprinkle, Patricia

Dust: (Part I: Sandstorms) by Bloom, Lochlan