Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (151 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

5.77Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Threatened miscarriage

Previous caesarean section (placenta praevia)

History of miscarriage and induced abortion (placenta praevia)

High parity (>3)

Older age (>35 years)

Maternal cocaine use

Smoking

Hypertensive disorders (placental abruption)

Multiple pregnancy

Domestic abuse (placental abruption)

355

355

Grade I Grade III Grade IV

Figure 16.4

Grades of placenta praevia. Source: Cruickshank and Shetty 2009, Figure 17.1, p. 117. Reproduced with permission of Cruickshank and Shetty.Signs and symptoms include:

355

355Grade I Grade III Grade IV

Figure 16.4

Grades of placenta praevia. Source: Cruickshank and Shetty 2009, Figure 17.1, p. 117. Reproduced with permission of Cruickshank and Shetty.Signs and symptoms include:

bleeding – since this can be concealed the degree of bleeding does not indicate the severity of the abruption

shock (see earlier section)

abdominal pain which may be associated with backache

abdominal tenderness on gentle palpation and where bleeding may be concealed there maybe increased abdominal girth and tension

fetal distress – a history of reduced or excessive movements may be reported and the fetalheart may show signs of distress or be absent.

Placenta praevia

Placenta praevia occurs when the placenta is implanted partially or wholly within the lower uterine segment. This is classified into four types (Figure 16.4):

Placenta praevia

Placenta praevia occurs when the placenta is implanted partially or wholly within the lower uterine segment. This is classified into four types (Figure 16.4):

Type I –

the placenta encroaches into the lower uterine segment but does not extend to the cervical os.

the placenta encroaches into the lower uterine segment but does not extend to the cervical os.

Type II –

the edge of the placenta reaches to the internal cervical os but does not cover it.

the edge of the placenta reaches to the internal cervical os but does not cover it.

Type III –

the placenta partially covers the internal cervical os.

the placenta partially covers the internal cervical os.

Type IV –

the placenta completely covers the internal cervical os.356

Management of APH

Any bleeding in pregnancy must be taken seriously and a hospital admission for assessment is necessary, however small and apparently insignificant the loss is. A history of the blood loss and the events associated with it, including any sexual intercourse, is vital, though where obvious heavy loss and shock are apparent the time taken for this may be limited. Clinical assessment of vital signs, particularly pulse and blood pressure, gentle abdominal examination and auscul- tation of the fetal heart should be carried out and a cardiotocograph (CTG) recording initiated. Vaginal examination should not be carried out, even with a speculum until a scan has ruled out placenta praevia. Blood tests for full blood count and clotting studies should be carried out and group and cross matching ordered if necessary. Where shock is a feature of presentation this should be treated as discussed in the previous section. The priority should be in resuscitating and stabilising the woman before delivering the baby. It should be remembered that deteriora- tion can occur rapidly so even if the blood loss is limited on admission, observation of maternal and fetal wellbeing should be continued.

Even a relatively small blood loss can be anxiety provoking for the woman and her family and it is important that all care is thoroughly explained and an atmosphere of calm professionalism is maintained. Communication between the midwife, the woman and her family should be honest and understanding of the concerns and anxiety the situation will provoke. Inappropriate reassurance is both unprofessional and damaging to trust and confidence.If there is a need to deliver the baby steroid injections to mature the fetal lungs will be required if the gestation is below 34 weeks, and where possible arrangements should be made for neonatal staff to meet the woman and her family. If delivery is not imminent and the woman is rhesus negative then anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered as an intramuscular (IM) injec- tion. A clear management plan for the remaining days/weeks of pregnancy should be agreed with the woman; this may include planned caesarean section or induction depending on the nature of the APH.Unfortunately the abruption or degree of bleeding may result in stillbirth. It is advisable if possible to deliver the baby vaginally in these circumstances and the contractions will help to control the bleeding. The support of the midwife in such circumstances is essential to the woman and her family, but peer support for the staff caring for the woman is also vital (see Chapter 17: ‘Bereavement and loss’ where care and support is discussed in greater depth).

Even a relatively small blood loss can be anxiety provoking for the woman and her family and it is important that all care is thoroughly explained and an atmosphere of calm professionalism is maintained. Communication between the midwife, the woman and her family should be honest and understanding of the concerns and anxiety the situation will provoke. Inappropriate reassurance is both unprofessional and damaging to trust and confidence.If there is a need to deliver the baby steroid injections to mature the fetal lungs will be required if the gestation is below 34 weeks, and where possible arrangements should be made for neonatal staff to meet the woman and her family. If delivery is not imminent and the woman is rhesus negative then anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered as an intramuscular (IM) injec- tion. A clear management plan for the remaining days/weeks of pregnancy should be agreed with the woman; this may include planned caesarean section or induction depending on the nature of the APH.Unfortunately the abruption or degree of bleeding may result in stillbirth. It is advisable if possible to deliver the baby vaginally in these circumstances and the contractions will help to control the bleeding. The support of the midwife in such circumstances is essential to the woman and her family, but peer support for the staff caring for the woman is also vital (see Chapter 17: ‘Bereavement and loss’ where care and support is discussed in greater depth).

Postpartum haemorrhage

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) can be primary or secondary. Primary PPH is generally definedas blood loss from the genital tract of 500 milliliters (mL) or more in the first 24 hours following birth (Crafter 2011). However it should be noted that for some women, e.g. those with pre- existing anaemia, a loss of less than 500 mL will constitute a PPH because the loss will be suf- ficient to cause symptoms of excessive blood loss. Major and minor PPH is categorised in Table16.2. See Box 16.6 for predisposing factors for PPH.

Table 16.2

Table 16.2

Categorisation of postpartum haemorrhageMinor PPH500–1000 mLMajor PPHModerate1000–2000 mLSevere>2000 mL

Box 16.6 Predisposing factors for postpartum haemorrhage

Box 16.6 Predisposing factors for postpartum haemorrhage

the placenta completely covers the internal cervical os.356

Management of APH

Any bleeding in pregnancy must be taken seriously and a hospital admission for assessment is necessary, however small and apparently insignificant the loss is. A history of the blood loss and the events associated with it, including any sexual intercourse, is vital, though where obvious heavy loss and shock are apparent the time taken for this may be limited. Clinical assessment of vital signs, particularly pulse and blood pressure, gentle abdominal examination and auscul- tation of the fetal heart should be carried out and a cardiotocograph (CTG) recording initiated. Vaginal examination should not be carried out, even with a speculum until a scan has ruled out placenta praevia. Blood tests for full blood count and clotting studies should be carried out and group and cross matching ordered if necessary. Where shock is a feature of presentation this should be treated as discussed in the previous section. The priority should be in resuscitating and stabilising the woman before delivering the baby. It should be remembered that deteriora- tion can occur rapidly so even if the blood loss is limited on admission, observation of maternal and fetal wellbeing should be continued.

Even a relatively small blood loss can be anxiety provoking for the woman and her family and it is important that all care is thoroughly explained and an atmosphere of calm professionalism is maintained. Communication between the midwife, the woman and her family should be honest and understanding of the concerns and anxiety the situation will provoke. Inappropriate reassurance is both unprofessional and damaging to trust and confidence.If there is a need to deliver the baby steroid injections to mature the fetal lungs will be required if the gestation is below 34 weeks, and where possible arrangements should be made for neonatal staff to meet the woman and her family. If delivery is not imminent and the woman is rhesus negative then anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered as an intramuscular (IM) injec- tion. A clear management plan for the remaining days/weeks of pregnancy should be agreed with the woman; this may include planned caesarean section or induction depending on the nature of the APH.Unfortunately the abruption or degree of bleeding may result in stillbirth. It is advisable if possible to deliver the baby vaginally in these circumstances and the contractions will help to control the bleeding. The support of the midwife in such circumstances is essential to the woman and her family, but peer support for the staff caring for the woman is also vital (see Chapter 17: ‘Bereavement and loss’ where care and support is discussed in greater depth).

Even a relatively small blood loss can be anxiety provoking for the woman and her family and it is important that all care is thoroughly explained and an atmosphere of calm professionalism is maintained. Communication between the midwife, the woman and her family should be honest and understanding of the concerns and anxiety the situation will provoke. Inappropriate reassurance is both unprofessional and damaging to trust and confidence.If there is a need to deliver the baby steroid injections to mature the fetal lungs will be required if the gestation is below 34 weeks, and where possible arrangements should be made for neonatal staff to meet the woman and her family. If delivery is not imminent and the woman is rhesus negative then anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered as an intramuscular (IM) injec- tion. A clear management plan for the remaining days/weeks of pregnancy should be agreed with the woman; this may include planned caesarean section or induction depending on the nature of the APH.Unfortunately the abruption or degree of bleeding may result in stillbirth. It is advisable if possible to deliver the baby vaginally in these circumstances and the contractions will help to control the bleeding. The support of the midwife in such circumstances is essential to the woman and her family, but peer support for the staff caring for the woman is also vital (see Chapter 17: ‘Bereavement and loss’ where care and support is discussed in greater depth).Postpartum haemorrhage

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) can be primary or secondary. Primary PPH is generally definedas blood loss from the genital tract of 500 milliliters (mL) or more in the first 24 hours following birth (Crafter 2011). However it should be noted that for some women, e.g. those with pre- existing anaemia, a loss of less than 500 mL will constitute a PPH because the loss will be suf- ficient to cause symptoms of excessive blood loss. Major and minor PPH is categorised in Table16.2. See Box 16.6 for predisposing factors for PPH.

Table 16.2

Table 16.2Categorisation of postpartum haemorrhageMinor PPH500–1000 mLMajor PPHModerate1000–2000 mLSevere>2000 mL

Box 16.6 Predisposing factors for postpartum haemorrhage

Box 16.6 Predisposing factors for postpartum haemorrhageOver-distension of the uterus, e.g. polyhydramnios, multiple pregnancy, macrosomic baby

Obesity

Raised blood pressure (more than 140/90)

Previous caesarean section

Previous PPH

Clotting disorders

Prolonged labour

Precipitate labour

Injudicious use of syntocinon

Instrumental or operative delivery

Mismanagement of the third stage

Cause

Approximate incidence

T

ONEAtonic uterus – feels ‘boggy’ on palpation70%

T

RAUMAPerineal, vaginal wall or cervical tears20%

T

ISSUERetained placenta and/or membrane10%

T

HROMBINClotting abnormalities1%

Table 16.3

Causes of postpartum haemorrhage (Anderson and Etches 2007)

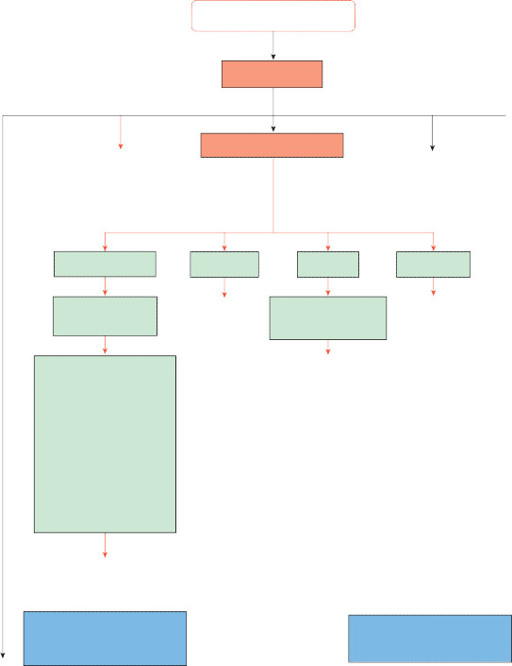

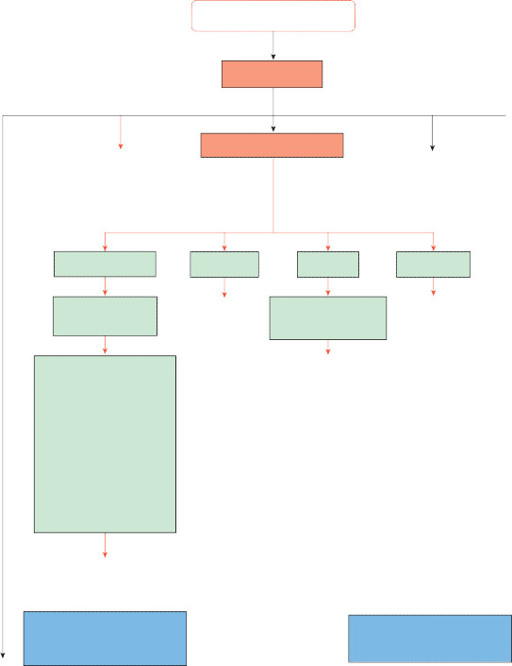

357Secondary PPH is defined as abnormal or excessive bleeding from the genital tract from 24 hours to 12 weeks after birth (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) 2009). Major obstetric haemorrhage remains a leading cause of maternal death; therefore timely recognition and intervention is vital to improve outcomes for affected women (CMACE 2011).The factors which can predispose to primary PPH are listed below; however in many cases no risk factors are identified (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009; RCOG 2009).The causes of primary PPH are usefully identified as the ‘Four Ts’ a mnemonic device which assists with both recognition of cause and appropriate management (Table 16.3).The ‘Four Ts’ should be systematically reviewed to establish the cause of PPH and initiate treatment (Figure 16.5). Combinations of causes can occur and therefore assessment should consider this.As can be seen from Table 16.3, the commonest cause of PPH is an atonic uterus where the uterus fails to adequately contract following delivery of the baby. The failure to contract means that the large venous sinuses within the uterus are not ligated by the muscle fibres and blood loss can be rapid. A partially contracted uterus can, however, lead to more insidious bleeding which presents as trickling loss that can be missed if the midwife is not observant. When bleed- ing occurs palpation of the uterus quickly determines whether it has contracted or not; it should not feel bulky or boggy (Tone). The contracted uterus feels firm centrally located on the abdomen, below the umbilicus. If it is not contracted, it is possible to ‘rub up’ a contraction

357Secondary PPH is defined as abnormal or excessive bleeding from the genital tract from 24 hours to 12 weeks after birth (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) 2009). Major obstetric haemorrhage remains a leading cause of maternal death; therefore timely recognition and intervention is vital to improve outcomes for affected women (CMACE 2011).The factors which can predispose to primary PPH are listed below; however in many cases no risk factors are identified (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009; RCOG 2009).The causes of primary PPH are usefully identified as the ‘Four Ts’ a mnemonic device which assists with both recognition of cause and appropriate management (Table 16.3).The ‘Four Ts’ should be systematically reviewed to establish the cause of PPH and initiate treatment (Figure 16.5). Combinations of causes can occur and therefore assessment should consider this.As can be seen from Table 16.3, the commonest cause of PPH is an atonic uterus where the uterus fails to adequately contract following delivery of the baby. The failure to contract means that the large venous sinuses within the uterus are not ligated by the muscle fibres and blood loss can be rapid. A partially contracted uterus can, however, lead to more insidious bleeding which presents as trickling loss that can be missed if the midwife is not observant. When bleed- ing occurs palpation of the uterus quickly determines whether it has contracted or not; it should not feel bulky or boggy (Tone). The contracted uterus feels firm centrally located on the abdomen, below the umbilicus. If it is not contracted, it is possible to ‘rub up’ a contraction

Primary PPH

Primary PPH

Call for help

Assess four Ts

Resuscitate

Assess ABCs, Oxygen, use of guerdal airway, large bore cannulae x2, IV fluids, obtain appropriate blood samples.

Ongoing monitoring

Vital signs, conscious level, fluid balance, urethral catheterisation

RepairAtonic uterus Trauma Tissue Thrombin

358Rub up a contractionPossible drugsTreatCheck placenta and membranes for completenessRemoval of tissueSyntometrine 1ml IMSyntocinon 5IU IVErgometrine 500 micrograms IV/IMSyntocinon in infusion fluid given by intravenous infusion at a rate that controls uterine atonyBI-Manual Compression

358Rub up a contractionPossible drugsTreatCheck placenta and membranes for completenessRemoval of tissueSyntometrine 1ml IMSyntocinon 5IU IVErgometrine 500 micrograms IV/IMSyntocinon in infusion fluid given by intravenous infusion at a rate that controls uterine atonyBI-Manual Compression

Communicate

With woman and her partner With the team members

Record keeping

Assign a member of the team to note actions and times accurately

Figure 16.5

Management of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH).abdominally by a firm circular massaging action with the palpating hand. If the placenta has not been delivered then this should be attempted once a contraction has been achieved. The placenta and membranes should be carefully checked for completeness as even a fragment of placenta or membrane can impede contraction of the uterus (Tissue). It is also useful to empty the bladder by means of a catheter as a full bladder can impede uterine contraction (and deliv- ery of the placenta). If possible, it is helpful to put the baby to the breast as this aids uterine contraction (see Chapter 8: ‘Postnatal midwifery care’ and Chapter 10: ‘Infant feeding’, where oxytocin release in response to nipple stimulation is discussed in greater depth). In excessive uterine bleeding, any placental products remaining in the uterus need to be removed in theatre. Following an actively managed third stage of labour where Syntometrine 1 mL IM (made up of 5 international units (IU) of oxytocin and 500 micrograms of Ergometrine) is commonly used in women who do not have pre-existing hypertension or pre-eclampsia; for further bleeding caused by an atonic uterus oxytocic drugs can be given either intravenously or intramuscularly. A single dose of Ergometrine 500 micrograms IV is recommended to treat an atonic uterus; however the same contraindications apply as for the use of Syntometrine. In a hospital setting, if the woman has pre-existing hypertension or pre-clampsia, Syntocinon 5 IU can be adminis- tered by slow intravenous injection. These interventions can be followed up by adding Syntoci- non to an intravenous solution and administering by continuous intravenous infusion, set at a rate to control uterine atony (Crafter 2011).Bi-manual compression of the uterus may need to be employed where bleeding persists despite drug treatments or where an infusion cannot be commenced (e.g. home birth). Bi-manual compression involves using one hand in the vagina to push up against the uterus whilst the other hand compresses the fundus through the abdominal wall. This is an uncomfortable pro- cedure for the woman, but can prevent excessive bleeding and provide time to gain access to alternative means of controlling the haemorrhage.Any form of haemorrhage is a frightening occurrence for patients and their families, but PPH occurs at a time when the woman and her partner are expecting to celebrate the birth of their baby, therefore it can be particularly distressing. The blood loss can be rapid and obvious and the woman’s partner in particular can find the experience to be very frightening. It is essential, therefore, that the interprofessional team behave with utmost professionalism and this is best achieved by there being a clear team leader who directs everyone in their assigned tasks and co-ordinates the care and management of the woman. It is also important that communication is maintained with the woman and her partner to keep them informed about the situation. They should be provided with the care and support they need throughout. In the drive to treat and manage the haemorrhage it is easy to forget to support the woman and her partner, but it is a very important part of the overall management and can make the difference between a situation where both are aware of a problem that is being appropriately and professionally managed and a distressingly bad experience with lasting psychological consequences.

Obstetric interventions

If the uterus fails to contract following administration of oxytocin (Syntometrine or Syntocinon)and/or Ergometrine then Carboprost (Hemabate) may be administered. Carboprost augments the contractility of the uterine muscles and 250 micrograms is administered by deep intramus- cular injection and can be repeated at 15–90 minute intervals (Billington and Stevenson 2007). Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin, may be given instead of Carboprost, but as this is

359360administered per rectum and there is as yet limited research to support its use (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009), it is not in common usage.Surgical interventions include uterine packing, the insertion of a tamponade balloon, a B-Lynch uterine compression suture or arterial embolisation. Hysterectomy is avoided if at all possible and is considered a ‘last resort’ intervention to save the woman’s life.The midwife’s role throughout obstetric management is to continue to ensure that the woman and her partner are kept fully informed and supported, to continue to monitor vital signs and ensure that all interventions are recorded accurately.

359360administered per rectum and there is as yet limited research to support its use (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009), it is not in common usage.Surgical interventions include uterine packing, the insertion of a tamponade balloon, a B-Lynch uterine compression suture or arterial embolisation. Hysterectomy is avoided if at all possible and is considered a ‘last resort’ intervention to save the woman’s life.The midwife’s role throughout obstetric management is to continue to ensure that the woman and her partner are kept fully informed and supported, to continue to monitor vital signs and ensure that all interventions are recorded accurately.

Continuing midwifery care

Complications following PPH include anaemia, genital tract infection and disseminated intra- vascular coagulation (DIC). It is essential for midwives to remain vigilant following the stabilisa- tion of the woman for signs and symptoms of complications. The monitoring of vital signs, fluid balance and blood profile should continue for some time following cessation of bleeding and analgesia should be administered as appropriate. A postnatal debrief is also good practice to allow the woman to discuss what happened and to have any of her queries and concerns addressed.

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia is a disorder unique to pregnancy that has the potential to cause both fetal andmaternal morbidity and mortality. It is characterised by hypertension and significant proteinuria and generally occurs after the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. Pre-eclampsia is now thought of as a syndrome (a collection of signs and symptoms that are recognised as a condition) rather than a disease that can be diagnosed by a specific test and it affects major organs and systems in a progressive and unpredictable manner (Robson 2002).There is a tendency to put figures to hypertension (Box 16.7), for example NICE (2010) define mild hypertension as 140–149/90–99 mmHg, but the absolutely vital aspect of monitoring blood pressure is to take into account the woman’s baseline recording. Therefore, if a woman’s booking blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg and this was the pattern of recording for the first half of pregnancy and she then presented at 28 weeks with a BP of 120/80 mmHg she is hyper- tensive as both systolic and diastolic pressures have increased by 20 mmHg. Levine et al. (2000) suggest that a rise of 30 mmHg in systolic or 15 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure (on two sepa- rate occasions) should be considered as a standard for the diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. It is recommended that automated blood pressure recording systems are not relied on for assessing

Cause

Approximate incidence

T

ONEAtonic uterus – feels ‘boggy’ on palpation70%

T

RAUMAPerineal, vaginal wall or cervical tears20%

T

ISSUERetained placenta and/or membrane10%

T

HROMBINClotting abnormalities1%

Table 16.3

Causes of postpartum haemorrhage (Anderson and Etches 2007)

357Secondary PPH is defined as abnormal or excessive bleeding from the genital tract from 24 hours to 12 weeks after birth (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) 2009). Major obstetric haemorrhage remains a leading cause of maternal death; therefore timely recognition and intervention is vital to improve outcomes for affected women (CMACE 2011).The factors which can predispose to primary PPH are listed below; however in many cases no risk factors are identified (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009; RCOG 2009).The causes of primary PPH are usefully identified as the ‘Four Ts’ a mnemonic device which assists with both recognition of cause and appropriate management (Table 16.3).The ‘Four Ts’ should be systematically reviewed to establish the cause of PPH and initiate treatment (Figure 16.5). Combinations of causes can occur and therefore assessment should consider this.As can be seen from Table 16.3, the commonest cause of PPH is an atonic uterus where the uterus fails to adequately contract following delivery of the baby. The failure to contract means that the large venous sinuses within the uterus are not ligated by the muscle fibres and blood loss can be rapid. A partially contracted uterus can, however, lead to more insidious bleeding which presents as trickling loss that can be missed if the midwife is not observant. When bleed- ing occurs palpation of the uterus quickly determines whether it has contracted or not; it should not feel bulky or boggy (Tone). The contracted uterus feels firm centrally located on the abdomen, below the umbilicus. If it is not contracted, it is possible to ‘rub up’ a contraction

357Secondary PPH is defined as abnormal or excessive bleeding from the genital tract from 24 hours to 12 weeks after birth (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) 2009). Major obstetric haemorrhage remains a leading cause of maternal death; therefore timely recognition and intervention is vital to improve outcomes for affected women (CMACE 2011).The factors which can predispose to primary PPH are listed below; however in many cases no risk factors are identified (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009; RCOG 2009).The causes of primary PPH are usefully identified as the ‘Four Ts’ a mnemonic device which assists with both recognition of cause and appropriate management (Table 16.3).The ‘Four Ts’ should be systematically reviewed to establish the cause of PPH and initiate treatment (Figure 16.5). Combinations of causes can occur and therefore assessment should consider this.As can be seen from Table 16.3, the commonest cause of PPH is an atonic uterus where the uterus fails to adequately contract following delivery of the baby. The failure to contract means that the large venous sinuses within the uterus are not ligated by the muscle fibres and blood loss can be rapid. A partially contracted uterus can, however, lead to more insidious bleeding which presents as trickling loss that can be missed if the midwife is not observant. When bleed- ing occurs palpation of the uterus quickly determines whether it has contracted or not; it should not feel bulky or boggy (Tone). The contracted uterus feels firm centrally located on the abdomen, below the umbilicus. If it is not contracted, it is possible to ‘rub up’ a contraction Primary PPH

Primary PPHCall for help

Assess four Ts

Resuscitate

Assess ABCs, Oxygen, use of guerdal airway, large bore cannulae x2, IV fluids, obtain appropriate blood samples.

Ongoing monitoring

Vital signs, conscious level, fluid balance, urethral catheterisation

RepairAtonic uterus Trauma Tissue Thrombin

358Rub up a contractionPossible drugsTreatCheck placenta and membranes for completenessRemoval of tissueSyntometrine 1ml IMSyntocinon 5IU IVErgometrine 500 micrograms IV/IMSyntocinon in infusion fluid given by intravenous infusion at a rate that controls uterine atonyBI-Manual Compression

358Rub up a contractionPossible drugsTreatCheck placenta and membranes for completenessRemoval of tissueSyntometrine 1ml IMSyntocinon 5IU IVErgometrine 500 micrograms IV/IMSyntocinon in infusion fluid given by intravenous infusion at a rate that controls uterine atonyBI-Manual CompressionCommunicate

With woman and her partner With the team members

Record keeping

Assign a member of the team to note actions and times accurately

Figure 16.5

Management of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH).abdominally by a firm circular massaging action with the palpating hand. If the placenta has not been delivered then this should be attempted once a contraction has been achieved. The placenta and membranes should be carefully checked for completeness as even a fragment of placenta or membrane can impede contraction of the uterus (Tissue). It is also useful to empty the bladder by means of a catheter as a full bladder can impede uterine contraction (and deliv- ery of the placenta). If possible, it is helpful to put the baby to the breast as this aids uterine contraction (see Chapter 8: ‘Postnatal midwifery care’ and Chapter 10: ‘Infant feeding’, where oxytocin release in response to nipple stimulation is discussed in greater depth). In excessive uterine bleeding, any placental products remaining in the uterus need to be removed in theatre. Following an actively managed third stage of labour where Syntometrine 1 mL IM (made up of 5 international units (IU) of oxytocin and 500 micrograms of Ergometrine) is commonly used in women who do not have pre-existing hypertension or pre-eclampsia; for further bleeding caused by an atonic uterus oxytocic drugs can be given either intravenously or intramuscularly. A single dose of Ergometrine 500 micrograms IV is recommended to treat an atonic uterus; however the same contraindications apply as for the use of Syntometrine. In a hospital setting, if the woman has pre-existing hypertension or pre-clampsia, Syntocinon 5 IU can be adminis- tered by slow intravenous injection. These interventions can be followed up by adding Syntoci- non to an intravenous solution and administering by continuous intravenous infusion, set at a rate to control uterine atony (Crafter 2011).Bi-manual compression of the uterus may need to be employed where bleeding persists despite drug treatments or where an infusion cannot be commenced (e.g. home birth). Bi-manual compression involves using one hand in the vagina to push up against the uterus whilst the other hand compresses the fundus through the abdominal wall. This is an uncomfortable pro- cedure for the woman, but can prevent excessive bleeding and provide time to gain access to alternative means of controlling the haemorrhage.Any form of haemorrhage is a frightening occurrence for patients and their families, but PPH occurs at a time when the woman and her partner are expecting to celebrate the birth of their baby, therefore it can be particularly distressing. The blood loss can be rapid and obvious and the woman’s partner in particular can find the experience to be very frightening. It is essential, therefore, that the interprofessional team behave with utmost professionalism and this is best achieved by there being a clear team leader who directs everyone in their assigned tasks and co-ordinates the care and management of the woman. It is also important that communication is maintained with the woman and her partner to keep them informed about the situation. They should be provided with the care and support they need throughout. In the drive to treat and manage the haemorrhage it is easy to forget to support the woman and her partner, but it is a very important part of the overall management and can make the difference between a situation where both are aware of a problem that is being appropriately and professionally managed and a distressingly bad experience with lasting psychological consequences.

Obstetric interventions

If the uterus fails to contract following administration of oxytocin (Syntometrine or Syntocinon)and/or Ergometrine then Carboprost (Hemabate) may be administered. Carboprost augments the contractility of the uterine muscles and 250 micrograms is administered by deep intramus- cular injection and can be repeated at 15–90 minute intervals (Billington and Stevenson 2007). Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin, may be given instead of Carboprost, but as this is

359360administered per rectum and there is as yet limited research to support its use (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009), it is not in common usage.Surgical interventions include uterine packing, the insertion of a tamponade balloon, a B-Lynch uterine compression suture or arterial embolisation. Hysterectomy is avoided if at all possible and is considered a ‘last resort’ intervention to save the woman’s life.The midwife’s role throughout obstetric management is to continue to ensure that the woman and her partner are kept fully informed and supported, to continue to monitor vital signs and ensure that all interventions are recorded accurately.

359360administered per rectum and there is as yet limited research to support its use (Mousa and Alfirevic 2009), it is not in common usage.Surgical interventions include uterine packing, the insertion of a tamponade balloon, a B-Lynch uterine compression suture or arterial embolisation. Hysterectomy is avoided if at all possible and is considered a ‘last resort’ intervention to save the woman’s life.The midwife’s role throughout obstetric management is to continue to ensure that the woman and her partner are kept fully informed and supported, to continue to monitor vital signs and ensure that all interventions are recorded accurately.Continuing midwifery care

Complications following PPH include anaemia, genital tract infection and disseminated intra- vascular coagulation (DIC). It is essential for midwives to remain vigilant following the stabilisa- tion of the woman for signs and symptoms of complications. The monitoring of vital signs, fluid balance and blood profile should continue for some time following cessation of bleeding and analgesia should be administered as appropriate. A postnatal debrief is also good practice to allow the woman to discuss what happened and to have any of her queries and concerns addressed.

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsiaPre-eclampsia is a disorder unique to pregnancy that has the potential to cause both fetal andmaternal morbidity and mortality. It is characterised by hypertension and significant proteinuria and generally occurs after the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. Pre-eclampsia is now thought of as a syndrome (a collection of signs and symptoms that are recognised as a condition) rather than a disease that can be diagnosed by a specific test and it affects major organs and systems in a progressive and unpredictable manner (Robson 2002).There is a tendency to put figures to hypertension (Box 16.7), for example NICE (2010) define mild hypertension as 140–149/90–99 mmHg, but the absolutely vital aspect of monitoring blood pressure is to take into account the woman’s baseline recording. Therefore, if a woman’s booking blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg and this was the pattern of recording for the first half of pregnancy and she then presented at 28 weeks with a BP of 120/80 mmHg she is hyper- tensive as both systolic and diastolic pressures have increased by 20 mmHg. Levine et al. (2000) suggest that a rise of 30 mmHg in systolic or 15 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure (on two sepa- rate occasions) should be considered as a standard for the diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. It is recommended that automated blood pressure recording systems are not relied on for assessing

Other books

Secrets of the Fall by Kailin Gow

Lincoln's Wizard by Tracy Hickman, Dan Willis

The Outlaws: Rafe by Mason, Connie

Seize the Night by Dean Koontz

IT Manager's Handbook: Getting Your New Job Done by Bill Holtsnider, Brian D. Jaffe

Girl in Love by Caisey Quinn

To Seduce an Omega by Kryssie Fortune

BEAST (A Coyotes of Mayhem MC Novel) (Motorcycle Club Bad Boy Romance) by Michelle, Aubrey

Eden by Candice Fox

The Sorceror's Revenge by Linda Sole