Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (152 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

3.72Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Box 16.7 Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

Gestational hypertension:

new hypertension presenting after 20 weeks without significant proteinuria.

Pre-eclampsia:

new hypertension presenting after 20 weeks with significant proteinuria.

Severe pre-eclampsia:

is pre-eclampsia with severe hypertension and/or with symptoms, and/or biochemical and/or haematological impairment.

Eclampsia:

is a convulsive condition associated with pre-eclampsia.(NICE 2010)

Box 16.8 Investigations for pre-eclampsia screening

Box 16.8 Investigations for pre-eclampsia screening

Gestational hypertension:

new hypertension presenting after 20 weeks without significant proteinuria.

Pre-eclampsia:

new hypertension presenting after 20 weeks with significant proteinuria.

Severe pre-eclampsia:

is pre-eclampsia with severe hypertension and/or with symptoms, and/or biochemical and/or haematological impairment.

Eclampsia:

is a convulsive condition associated with pre-eclampsia.(NICE 2010)

Box 16.8 Investigations for pre-eclampsia screening

Box 16.8 Investigations for pre-eclampsia screening24-hour urine collection and analysis for total protein and creatinine clearance

Full blood count

Blood chemistry

Liver function tests

Coagulation profile

Scan for fetal size, amniotic fluid volume and Doppler studiesblood pressure due to the risk of underestimation; manual recording by means of a sphyg- momanometer is the method of choice (Lewis 2001). The incidence of pre-eclampsia is esti- mated at 2–3% with eclampsia affecting approximately 1:2000 pregnancies and although the incidence of eclampsia is falling, it remains a significant cause of maternal mortality (CMACE 2011). The exact aetiology of pre-eclampsia remains unknown, but many theories suggest that there is a placental trigger followed by a maternal systemic response (Billington and Stevenson 2007). There is thought to be a familial tendency with a 25% increase in risk if the woman’s mother had pre-eclampsia and a 40% increase if her sister suffered from it. There is an increased risk associated with multiple pregnancies, and if a hydatidiform mole forms then the condition may well appear before 20 weeks.The condition is defined by the hypertension and proteinuria that are easily monitored during pregnancy by regular blood pressure measurements and urinalysis; however it also causes oedema, coagulopathy, impaired renal function and liver dysfunction. Additionally the affects of pre-eclampsia on placental function can lead to intrauterine growth retardation and fetal hypoxia (see Box 16.8, Investigations for pre-eclampsia screening). It is essential, therefore, that the progress and effects of pre-eclampsia are fully investigated on diagnosis.Hypertension can be managed by drug therapy and NICE (2010) recommend Labetalol as a first line treatment although Methyldopa and Nifedipine may also be used. Blood pressure should be monitored to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment. A plan of care is essential and women should be encouraged to participate in the decision making process particularly as induction of labour may be necessary.Severe or fulminating pre-eclampsia is the worsening maternal condition that signals impend- ing eclampsia (Holmes and Baker 2006; see Box 16.9) and it is important that midwives recog- nise the signs and symptoms and ensure that medical assessment and treatment is accessed urgently. The aim of care and management is to control hypertension, inhibit convulsions and prevent coma and therefore prevent fetal and maternal mortality.Eclampsia is the occurrence of convulsions after 20 weeks gestation and up to 10 days post- delivery in association with the signs and symptoms of pre-eclampsia. Whilst many women will demonstrate developing pre-eclampsia in the days or weeks preceding an eclamptic fit, some will not experience any obvious deviation from the norm until the convulsion occurs. (See Box

for immediate care of the woman with eclampsia.) It is important that a diagnosis of eclampsia is not assumed, but that other cerebral causes of convulsions such as epilepsy are also considered. Antenatal eclampsia is associated with both maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity; therefore once the woman is stabilised, delivery should follow as soon as possible.

361

361

Box 16.9 Signs and symptoms of fulminating pre-eclampsia

Box 16.9 Signs and symptoms of fulminating pre-eclampsia

361

361 Box 16.9 Signs and symptoms of fulminating pre-eclampsia

Box 16.9 Signs and symptoms of fulminating pre-eclampsiaSharp rise in blood pressure

Diminished urine output – increased proteinuria

Headache – frontal persistent

Drowsiness and confusion

Visual disturbances

Nausea and vomiting

Excessive swelling, particularly of the face and neck362

Box 16.10 Immediate care of the eclamptic woman

Box 16.10 Immediate care of the eclamptic woman

Box 16.10 Immediate care of the eclamptic woman

Box 16.10 Immediate care of the eclamptic woman

Summon help (obstetric team and an anaesthetist or paramedic ambulance as appropriate).

Protect the woman from injury during the fit.

Manage Airway, Breathing and Circulation according to the principles of resuscitation.

Monitor and record vital signs (including fetal heart if appropriate).

Record all drug treatment accurately as given.An eclamptic fit generally presents in distinct phases:

Prodromal

– where the fit is preceded by possible visual disturbances, muscular twitching, facial congestion, foaming at the mouth and deepening loss of consciousness.

– where the fit is preceded by possible visual disturbances, muscular twitching, facial congestion, foaming at the mouth and deepening loss of consciousness.

Tonic

– generalised muscular spasm and rigidity, absent respiration and cyanosis.

– generalised muscular spasm and rigidity, absent respiration and cyanosis.

Tonoclonic

– intermittent contraction and relaxation of all muscles (convulsive movement)associated with stertorous breathing, increased salivation and possible incontinence of urine and faeces.

– intermittent contraction and relaxation of all muscles (convulsive movement)associated with stertorous breathing, increased salivation and possible incontinence of urine and faeces.

Post-ictal state

– gradual return to consciousness, re-establishment of respiration (breathingmay be deep and rapid). The woman may be lethargic or in a confused and agitated state following a fit and may not remember what has happened.The current accepted treatment of eclampsia is magnesium sulphate which has been shown to be an effective hypotensive and anticonvulsant agent (Duley et al. 2010). The protocols for dosage may vary locally, but a loading dose given by slow intravenous injection is then followed by a slow intravenous infusion. Toxicity can occur leading to depressed respiration, drowsiness, loss of tendon reflexes, double vision and reduced urine output; therefore it is essential that the overall condition of the woman is monitored both for hypertension and associated complica- tions and for signs of toxicity. Blood levels of magnesium will be checked during treatment. Psychological support for the woman and her family is very important as this is a time of great anxiety. Transfer to a general intensive care or high dependency unit may be necessary in some cases and midwifery care should not only be continued, but is essential in providing ongoing support and specialist care.

Box 16.11 Pre-disposing risk factors for shoulder dystocia

Box 16.11 Pre-disposing risk factors for shoulder dystocia

Pre-pregnancy or antenatal factors:

– gradual return to consciousness, re-establishment of respiration (breathingmay be deep and rapid). The woman may be lethargic or in a confused and agitated state following a fit and may not remember what has happened.The current accepted treatment of eclampsia is magnesium sulphate which has been shown to be an effective hypotensive and anticonvulsant agent (Duley et al. 2010). The protocols for dosage may vary locally, but a loading dose given by slow intravenous injection is then followed by a slow intravenous infusion. Toxicity can occur leading to depressed respiration, drowsiness, loss of tendon reflexes, double vision and reduced urine output; therefore it is essential that the overall condition of the woman is monitored both for hypertension and associated complica- tions and for signs of toxicity. Blood levels of magnesium will be checked during treatment. Psychological support for the woman and her family is very important as this is a time of great anxiety. Transfer to a general intensive care or high dependency unit may be necessary in some cases and midwifery care should not only be continued, but is essential in providing ongoing support and specialist care.

Box 16.11 Pre-disposing risk factors for shoulder dystocia

Box 16.11 Pre-disposing risk factors for shoulder dystociaPre-pregnancy or antenatal factors:

Maternal Body Mass Index >30 kg/m

2

2

Diabetes mellitus – pre-existing or gestational

Previous shoulder dystocia

Induction of labour

Excessive maternal weight gain

Macrosomia

Post-term pregnancy

Intrapartum factors

Intrapartum factors

Prolonged first stage of labour

Prolonged second stage

Oxytocin augmentation

Operative vaginal delivery(RCOG 2012; Allen 2011)

363

363

Shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia is defined as a cephalic vaginal delivery where additional obstetric manoeu-vres are required to deliver the fetus after the head has delivered (RCOG 2012). It occurs when the anterior shoulder of the fetus becomes impacted on the maternal symphysis pubis or, less commonly, the posterior shoulder on the sacral promontory. Its incidence is reported with a wide variety of figures but the largest studies suggest up to 0.6 to 0.7% of vaginal births and it can be associated with significant perinatal mortality, as well as maternal morbidity in terms of perineal trauma and haemorrhage.Although it is not possible to predict shoulder dystocia, there are a number of pre-disposing factors that put a woman at higher risk (see Box 16.11). Many occurrences however are in the absence of any risk factors. Shoulder dystocia is usually first suspected when there is some dif- ficulty in delivering the face by extension, often extra maternal effort is required to free the chin from the perineum. There is often a noticeable retraction of the head, usually referred to as ‘turtle-necking’ resulting in the chin being forced up into the perineum and the cheeks puffing out. Restitution will often not occur spontaneously and gentle traction with the next contrac- tion does not result in the birth of the body. Once recognised, it is imperative that help is sum- moned immediately as there is a low rate of hypoxia ischaemic injury to the baby if the head-to-body delivery time is less than five minutes (Leung et al. 2011).It is important to remember that excessive traction to the head must

never

be applied; simi- larly, fundal pressure must

never

be instigated as both of these will dramatically increase the chance of brachial plexus injury, the most common injury to the neonate following a case of shoulder dystocia, although this injury can occur without such complications at delivery (Dou- mouchtsis and Arulkumaran 2009). It is highlighted in the RCOG (2012) Shoulder Dystocia

H

elp

Guidelines, that maternal pushing should be discouraged as this may exacerbate the situation, further impacting the shoulders.Maternal and fetal morbidity can be reduced if staff have had training in how to manage this obstetric emergency and have a clear strategy to follow (Draycott et al. 2008; Allen 2011). A widely used strategy is that prompted by the mnemonic HELPERR:Call for assistance by activating the recognised obstetric emergency drill appropriate to the setting.

E

valuate for episiotomy

Although this is a bony obstruction problem, it can be useful to perform an episiotomy if the perineum is restricting access to perform the internal manoeuvres.

L

egs

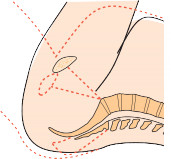

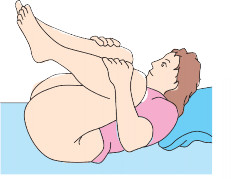

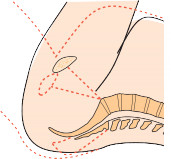

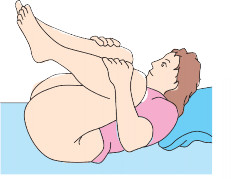

Position the mother to lie flat with both thighs hyper flexed up onto the abdomen (known as McRoberts’ manoeuvre; see Figure 16.6). This has a twofold effect of straightening the lum- bosacral arch and flexing the fetal spine, allowing the posterior shoulder to pass over the sacral promontory and drop into the hollow of the sacrum. This can then allow the anterior shoulder to pass under the symphysis pubis and deliver.

364(a)

364(a)

(c)(b)

(c)(b)

Figure 16.6

Figure 16.6

McRoberts’ manoeuvre. Source: Simkin and Ancheta 2011, Figure 8.7, p. 263. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

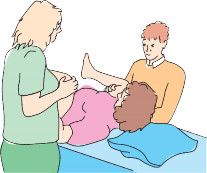

Figure 16.7

Figure 16.7

Suprapubic pressure. Source: Simkin and Ancheta 2011, Figure 8.8, p. 264. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

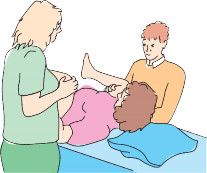

P

ressure

External pressure applied over the symphysis pubis, similar to the action of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but from behind the fetal shoulder at an angle of 45 degrees, can assist in releas- ing the anterior shoulder by moving it into the oblique angle (Figure 16.7).In practice, it is often found that these two manoeuvres alone will resolve the problem and have been reported successful in up to 90% of cases (RCOG 2012). If unsuccessful then further measures must be employed.

365

365

E

nter

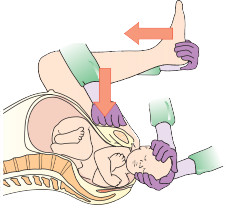

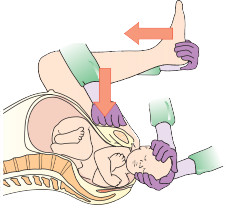

Sometimes a more direct pressure on the fetal shoulders is necessary to reduce the distance between the shoulders and rotate the fetus into the oblique diameter. This is performed by positioning two fingers under the pubic arch, behind the anterior shoulder and pushing it forward. This may be accompanied by pressure on the front of the posterior shoulder. If this is unsuccessful a rotation can be attempted in the opposite direction with the manoeuvre termed Woods Screw.For this manoeuvre, pressure needs to be applied behind the posterior shoulder, pushing it forward and performing a 180 degree rotation to make the anterior shoulder become the pos- terior one, thus releasing it and allowing delivery (see Figure 16.8).

R

emove the posterior arm

This manoeuvre is technically difficult, especially if the baby’s posterior arm is not flexed across its chest. The person attempting delivery is required to insert their hand in front of the baby to grasp the forearm of the posterior arm and sweep it across the chest and over the face to deliver it. If the arm does not deliver, it can be used to assist in rotation as in the Woods Screw. This manoeuvre does carry a higher risk of fracturing the humerus of the neonate.

R

oll the patient

If possible, the woman may be assisted to move into the‘all-fours’ position and a further attempt made to deliver the posterior shoulder (which is now uppermost).This final manoeuvre may be attempted first in the home birth situation, where extra person- nel are not available to perform the McRoberts’ manoeuvre. Indeed the order of all of these may be adjusted according to the situation but

no longer than 30 seconds

should be spent on each attempt before moving onto another.

363

363Shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia is defined as a cephalic vaginal delivery where additional obstetric manoeu-vres are required to deliver the fetus after the head has delivered (RCOG 2012). It occurs when the anterior shoulder of the fetus becomes impacted on the maternal symphysis pubis or, less commonly, the posterior shoulder on the sacral promontory. Its incidence is reported with a wide variety of figures but the largest studies suggest up to 0.6 to 0.7% of vaginal births and it can be associated with significant perinatal mortality, as well as maternal morbidity in terms of perineal trauma and haemorrhage.Although it is not possible to predict shoulder dystocia, there are a number of pre-disposing factors that put a woman at higher risk (see Box 16.11). Many occurrences however are in the absence of any risk factors. Shoulder dystocia is usually first suspected when there is some dif- ficulty in delivering the face by extension, often extra maternal effort is required to free the chin from the perineum. There is often a noticeable retraction of the head, usually referred to as ‘turtle-necking’ resulting in the chin being forced up into the perineum and the cheeks puffing out. Restitution will often not occur spontaneously and gentle traction with the next contrac- tion does not result in the birth of the body. Once recognised, it is imperative that help is sum- moned immediately as there is a low rate of hypoxia ischaemic injury to the baby if the head-to-body delivery time is less than five minutes (Leung et al. 2011).It is important to remember that excessive traction to the head must

never

be applied; simi- larly, fundal pressure must

never

be instigated as both of these will dramatically increase the chance of brachial plexus injury, the most common injury to the neonate following a case of shoulder dystocia, although this injury can occur without such complications at delivery (Dou- mouchtsis and Arulkumaran 2009). It is highlighted in the RCOG (2012) Shoulder Dystocia

H

elp

Guidelines, that maternal pushing should be discouraged as this may exacerbate the situation, further impacting the shoulders.Maternal and fetal morbidity can be reduced if staff have had training in how to manage this obstetric emergency and have a clear strategy to follow (Draycott et al. 2008; Allen 2011). A widely used strategy is that prompted by the mnemonic HELPERR:Call for assistance by activating the recognised obstetric emergency drill appropriate to the setting.

E

valuate for episiotomy

Although this is a bony obstruction problem, it can be useful to perform an episiotomy if the perineum is restricting access to perform the internal manoeuvres.

L

egs

Position the mother to lie flat with both thighs hyper flexed up onto the abdomen (known as McRoberts’ manoeuvre; see Figure 16.6). This has a twofold effect of straightening the lum- bosacral arch and flexing the fetal spine, allowing the posterior shoulder to pass over the sacral promontory and drop into the hollow of the sacrum. This can then allow the anterior shoulder to pass under the symphysis pubis and deliver.

364(a)

364(a) (c)(b)

(c)(b) Figure 16.6

Figure 16.6McRoberts’ manoeuvre. Source: Simkin and Ancheta 2011, Figure 8.7, p. 263. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 16.7

Figure 16.7Suprapubic pressure. Source: Simkin and Ancheta 2011, Figure 8.8, p. 264. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

P

ressure

External pressure applied over the symphysis pubis, similar to the action of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but from behind the fetal shoulder at an angle of 45 degrees, can assist in releas- ing the anterior shoulder by moving it into the oblique angle (Figure 16.7).In practice, it is often found that these two manoeuvres alone will resolve the problem and have been reported successful in up to 90% of cases (RCOG 2012). If unsuccessful then further measures must be employed.

365

365E

nter

Sometimes a more direct pressure on the fetal shoulders is necessary to reduce the distance between the shoulders and rotate the fetus into the oblique diameter. This is performed by positioning two fingers under the pubic arch, behind the anterior shoulder and pushing it forward. This may be accompanied by pressure on the front of the posterior shoulder. If this is unsuccessful a rotation can be attempted in the opposite direction with the manoeuvre termed Woods Screw.For this manoeuvre, pressure needs to be applied behind the posterior shoulder, pushing it forward and performing a 180 degree rotation to make the anterior shoulder become the pos- terior one, thus releasing it and allowing delivery (see Figure 16.8).

R

emove the posterior arm

This manoeuvre is technically difficult, especially if the baby’s posterior arm is not flexed across its chest. The person attempting delivery is required to insert their hand in front of the baby to grasp the forearm of the posterior arm and sweep it across the chest and over the face to deliver it. If the arm does not deliver, it can be used to assist in rotation as in the Woods Screw. This manoeuvre does carry a higher risk of fracturing the humerus of the neonate.

R

oll the patient

If possible, the woman may be assisted to move into the‘all-fours’ position and a further attempt made to deliver the posterior shoulder (which is now uppermost).This final manoeuvre may be attempted first in the home birth situation, where extra person- nel are not available to perform the McRoberts’ manoeuvre. Indeed the order of all of these may be adjusted according to the situation but

no longer than 30 seconds

should be spent on each attempt before moving onto another.

Other books

Unnatural Souls by Linda Foster

Indigo Squad by Tim C. Taylor

Virginia Henley by The Raven, the Rose

Playing the Playboy by Noelle Adams

Real War by Richard Nixon

The Fire Children by Lauren Roy

Grizzly by Gary Paulsen

Death and the Penguin by Kurkov, Andrey

A Dawn Like Thunder by Douglas Reeman