Secondary Schizophrenia (24 page)

Read Secondary Schizophrenia Online

Authors: Perminder S. Sachdev

the ear. Schizophr Res, 1995.

17

:

A.,

et al.

State dependent changes

Br J Psychiatry, 1991.

158

:328–

289–91.

in error monitoring in

36.

88. Bartlett M. The sensory acuity of

schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res,

78. Karp B. I., Garvey M., Jacobsen L.

psychopathic individuals: a

2004.

38

:347–56.

K.,

et al.

Abnormal neurologic

comparison of the auditory acuity

69. Kathmann N., Von Recum S.,

maturation in adolescents with

of psychoneurotic and dementia

Haag C.,

et al.

Electrophysio-

early-onset schizophrenia. Am J

praecox cases with that of normal

logical evidence for reduced latent

Psychiatry, 2001.

158

:118–22.

individuals. Psychiatr Q, 1935.

inhibition in schizophrenic

79. Hyde T., Hotson J., Kleinman J.

9

:422–5.

patients. Schizophr Res, 2000.

Differential diagnosis of

89. Ludwig A. M., Wood B. S., Jr.,

58

45

:103–14.

choreiform tardive dyskinesia.

Downs M. P. Auditory studies in

Chapter 4 – The neurologic examination in schizophrenia

schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry,

examination. Psychiatr J Univ Ott,

106. Rubino F. A. Neurologic

1962.

119

:122–7.

1989.

14

:554–6.

complications of alcoholism.

90. Hawkes C. Olfaction in

98. Sanders R. D., Joo Y. H., Almasy

Psychiatr Clin North Am, 1992.

neurodegenerative disorder. Adv

L.,

et al.

Are neurologic

15

:359–72.

Otorhinolaryngol, 2006.

63

:

examination abnormalities

107. Casanova M. F. Wernicke’s disease

133–5.

heritable? A preliminary study.

and schizophrenia: a case report

91. Kopala L., Clark C., Hurwitz T.

Schizophr Res, 2006.

86

:172–80.

and review of the literature. Int J

Olfactory deficits in neuroleptic

99. Jenkyn L. R., Walsh D. B., Culver

Psychiatry Med, 1996.

26

:319–28.

naive patients with schizophrenia.

C. M.,

et al.

Clinical signs in

108. Allen D. N., Goldstein G., Forman

Schizophr Res, 1992.

8

:245–

diffuse cerebral dysfunction.

S. D.,

et al.

Neurologic

50.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry,

examination abnormalities in

92. Sirota P., Davidson B., Mosheva

1977.

40

:956–66.

schizophrenia with and without a

T.,

et al.

Increased olfactory

100. Arango C., Bartko J. J., Gold J. M.,

history of alcoholism.

sensitivity in first episode

et al.

Prediction of

Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol

psychosis and the effect of

neuropsychological performance

Behav Neurol, 2000.

13

:184–7.

neuroleptic treatment on olfactory

by neurological signs in

109. Goldstein G., Allen D. N., Sanders

sensitivity in schizophrenia.

schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry,

R. D. Sensory-perceptual

Psychiatry Res, 1999.

86

:

1999.

156

:1349–57.

dysfunction in patients with

143–53.

101. Sanders R., Shuepbach D.,

schizophrenia and comorbid

93. Collins L., Stone L. Pain

Keshavan M. S.,

et al.

Neurologic

alcoholism. J Clin Exp

sensitivity, age and activity level in

exam abnormalities and

Neuropsychol, 2002.

24

:1010–16.

chronic schizophrenics and

neuropsychological performances

110. Kinney D. K., Yurgelun-Todd D.

normals. Br J Psychiatry, 1966.

in neuroleptic-naive psychosis.

A., Woods B. T. Neurologic signs

112

:33–5.

J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci,

of cerebellar and cortical sensory

94. Nasrallah H. A., Tippin J.,

2004.

16

:480–7.

dysfunction in schizophrenics and

Mccalley-Whitters M.,

et al.

102. Moles J. K., Franchina J. J., Sforza

their relatives. Schizophr Res,

Neurological differences between

P. P. Neurological deficits and CT

1999.

35

:99–104.

paranoid and nonparanoid

findings in psychiatric patients.

111. Desmukh A., Rosenbloom M.,

schizophrenia: Part III.

Psychosomatics, 1998.

39

:394–5.

Pfefferbaum A.,

et al.

Clinical

Neurological soft signs. J Clin

103. Bae C. J., Pincus J. H. Neurologic

signs of cerebellar dysfunction in

Psychiatry, 1982.

43

:310–2.

signs predict periventricular white

schizophrenia, alcoholism and

95. Detre T., Bunney W. E. Jr. Human

matter lesions on MRI. Can J

their comorbidity. Schizophr Res,

vibration perception. II. A

Neurol Sci, 2004.

31

:242–7.

2002.

57

:281–91.

preliminary report on vibration

104. Murphy K. C. (2002)

112. Bartzokis G., Beckson M.,

perception in psychiatric patients.

Schizophrenia and

Wirshing D. A.,

et al.

Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1961.

velo-cardio-facial syndrome.

Choreoathetoid movements in

4

:615–8.

Lancet, 2002.

359

:426–30.

cocaine dependence. Biol

96. Fink M., Green M., Bender M. B.

105. Baumann N., Turpin J. C., Lefevre

Psychiatry, 1999.

45

:1630–5.

The face–hand test as a diagnostic

M.,

et al.

Motor and psycho-

113. Bauer L. O. Resting hand tremor

sign of organic mental syndrome.

cognitive clinical types in adult

in abstinent cocaine-dependent,

Neurology, 1952.

2

:46–58.

metachromatic leukodystrophy:

alcohol-dependent, and

97. Patten S. B., Lamarre C. J. The

genotype/phenotype

polydrug-dependent patients.

face–hand test: a useful addition

relationships? J Physiol Paris,

Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 1996.

to the psychiatric physical

2002.

96

:301–6.

20

:1196–201.

59

Section 2

The neurology of schizophrenia

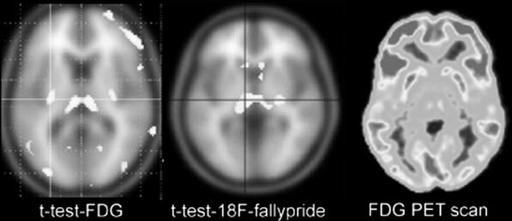

5 Functionalneuroimaginginschizophrenia

Serge A. Mitelman, Jane Zhang, and Monte S. Buchsbaum

Acknowledgments

: This work was supported by

circulation-borne products of the liver and pancreas

NIMH grants P50 MH 66392–01, MH 60023, and

have made blood chemistry sampling and postmortem

MH 56489 to Dr. Buchsbaum and by NARSAD

assessment fruitful approaches, the regional com-Young Investigator and NIMH MH 077146 awards to

plexity and behavioral productions of the brain have

Dr. Mitelman.

made these methods less informative for the brain,

the target organ of schizophrenia. In this review, we

Facts box

describe brain–function research in psychiatry from

its inception with the electroencephalogram (EEG)

1. Functional imaging has shown decreases in

to the current advances in regional metabolism,

resting activity and the amount of activation

blood flow, receptor chemistry, and most recently,

by cognitive tasks in the frontal lobe,

the deficiencies in the dynamic connectivity of

temporal lobe, cingulate gyrus, and thalamus

circuits.

in schizophrenia.

2. Decreases in activity appear in regions that

Electroencephalography, cerebral

also show decreases in volume when

anatomical imaging techniques are used.

blood flow, and the earliest functional

3. The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of

imaging of schizophrenia

these activities and volume changes remain

Among the earliest observations in Jena, Germany, of

unclear.

Hans Berger, the developer of the electroencephalo-4. Psychotic symptoms include auditory and

gram, was the observation of diminished occipital

visual hallucinations, paranoid delusions or

alpha activity in patients with schizophrenia

[1].

This

paranoid trends, ideas of reference, ideas of

reduction in smooth rhythmic resting activity over

influence, catatonia, and atypical features

the visual cortex, which is observed in normal indi-such as complex perceptual distortions.

viduals when they open their eyes, is consistent with

Although a link between psychotic

modern computer analysis of the electrical signals

symptoms and basal ganglia, temporal lobe,

and with concepts of heightened sensory responsive-and frontal lobe pathology is supported,

ness, the symptoms of hallucinations, and complex

symptoms appear to be variable after the

regional changes in brain function seen in schizophre-onset of neuronal damage, and remission has

nia. The earliest cerebral blood oxygen and glucose

also been reported.

studies by Joseph Wortis and colleagues

[2]

at Belle-5. Treatment is largely symptomatic but links

vue Hospital in New York assessed arteriovenous dif-between brain region change and symptom

ference and did not find patients with schizophre-change are being established.

nia to be different from controls. Seymour Kety and

colleagues, in 1948 at the University of Pennsylva-nia, studied cerebral blood flow (CBF) and simi-

Brain function and schizophrenia

larly did not find differences in total CBF, but sug-Instruments for observing and assessing organ

gested that regional blood flow abnormalities might

function have been technical eye-opening scientific

exist

[3].The

current regional approach to brain imag-advances in understanding of disease in the last 100

ing in schizophrenia began with the work of David

60

years. Although the uniform tissue composition and

Ingvar and coworkers in Lund, Sweden

[4]

who

Chapter 5 – Functional neuroimaging in schizophrenia

Figure 5.1

Hypofrontality: individual

unmedicated patient with schizophrenia

showing areas in prefrontal cortex (including

Brodmann areas 10, 47, 9, 46) with relative

metabolic rate two standard deviations below

the normal control comparison group.

introduced regional functional imaging and staged

remains to be elucidated, for although hypofrontality

cognitive tasks to identify specific brain regions acti-has been demonstrated in neuroleptic-na¨ıve patients

vated by different mental activities and initiated the

[25],

treatment with antipsychotic agents may con-current direction of research in functional brain imag-tribute to its severity

[26].

ing in schizophrenia.

The newly emergent imaging technologies have