Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (41 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

5.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

So New Market’s sundown ordinance went right back into effect the following night.

Twenty years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act made it illegal for a bar owner to keep African Americans out of his or her tavern, the city officials of New Market thought they had the power to keep them out of an entire town, at least after dark. Apparently they still do, for the 2000 census showed no African Americans in New Market, and none in Gravity, Bedford, or Villisca. Indeed, neither Taylor County nor adjoining Adams County had a single black household .

60

Errors of Inclusion and ExclusionTwenty years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act made it illegal for a bar owner to keep African Americans out of his or her tavern, the city officials of New Market thought they had the power to keep them out of an entire town, at least after dark. Apparently they still do, for the 2000 census showed no African Americans in New Market, and none in Gravity, Bedford, or Villisca. Indeed, neither Taylor County nor adjoining Adams County had a single black household .

60

In the end, I did my damnedest to find the data. But all the deception and omissions, especially in the written record, make sundown towns hard to research. Therefore I cannot be sure of all the claims made about sundown towns in this book. Some towns I list as sundown may not be. Some may merely have happened to have no African Americans, decade after decade. There is also the question of change. A town may have been sundown for decades but may not be sundown today. Chapter 14, “Sundown Towns Today,” describes the relaxation of sundown policies in many towns and suburbs since about 1980. I certainly do not claim that all the towns that I describe as confirmed are all-white on purpose to this day.

When deliberating whether to list a town as sundown based on sometimes scanty information, I tried to minimize errors of inclusion and exclusion. An error of inclusion would be falsely classing a town as sundown when it was not. Such a mistake could upset townspeople who might protest that they are

not

racist and the town never had a sundown policy. Uncorrected, the inaccuracy might also deter black families from moving to the town. I don’t mean to cause these problems, and I apologize for any such errors. All readers should check out the history of a given town for themselves, rather than taking my word for its policies. Please give me feedback ([email protected]) if you learn that I have wrongly listed a town as sundown when it was not; I will make a correction on my web site and if possible in future editions of this book. In practical terms, however, I doubt that any notoriety a town mistakenly receives from its listing in my book will make a significant difference to its future. Moreover, if a town protests that it

is

welcoming, such an objection itself ends the harm by countering the notoriety and increasing the likelihood that African American families will test its waters and experience that welcome

61

—a happy result.

not

racist and the town never had a sundown policy. Uncorrected, the inaccuracy might also deter black families from moving to the town. I don’t mean to cause these problems, and I apologize for any such errors. All readers should check out the history of a given town for themselves, rather than taking my word for its policies. Please give me feedback ([email protected]) if you learn that I have wrongly listed a town as sundown when it was not; I will make a correction on my web site and if possible in future editions of this book. In practical terms, however, I doubt that any notoriety a town mistakenly receives from its listing in my book will make a significant difference to its future. Moreover, if a town protests that it

is

welcoming, such an objection itself ends the harm by countering the notoriety and increasing the likelihood that African American families will test its waters and experience that welcome

61

—a happy result.

An error of exclusion would be missing a town that kept out African Americans. Such a mistake might encourage the town to stay sundown and to continue to cover up its policy. People of goodwill in the community might imagine no problem exists, while my erroneous omission would hardly bother those in the town who want to maintain its sundown character. Such an error might also mislead a black family to move in without fully understanding the risk. Nationally, such errors might convince readers that sundown towns have been less common than is really the case, thus lessening readers’ motivation to eliminate sundown policies and draining our nation’s reservoir of some of the goodwill needed to effect change.

Some towns I have confirmed as sundown through a single specific written source, often by a forthright local historian, or a single oral statement with convincing details. For example, the following anecdote, told to me by a Pinckneyville native then in graduate school, would by itself have convinced me that Pinckneyville, Illinois, was a sundown town and displayed a sign:

Pinckneyville was indeed a sundown town. I grew up three miles east of town, and I can vividly recall—though my mom and aunts vehemently deny it—seeing a sign under the city limits sign, saying “No Coloreds After Dark.” I don’t know when they came down; I’d presume late ’60s/early ’70s, because I don’t recall them when I was of junior-high age. However, I am sure they did exist, because one of my most vivid memories is of being four or five years old and driving to town with my dad. I was becoming a voracious reader, and I read the sign and said, “But that’s wrong, Daddy. They’re ‘colors’ (our local word for ‘Crayolas’), not ‘coloreds.’ ” He laughed and laughed at me, finally saying, “No, baby, not ‘colors,’ ‘coloreds’—you know, darkies. It’s just a nicer way of saying ‘niggers.’ ”

62

In fact, many other sources, written and oral, confirm Pinckneyville. For other towns the evidence is considerably weaker, not always yielding a definite yes-or-no answer.

63

I believe my responsibility is to state the most likely conclusion based on the preponderance of the evidence I have, even though often that conclusion may not be proven beyond the shadow of a doubt. To be too insistent on solid proof before listing a town as sundown risks an error of exclusion. To list a town as sundown with inadequate evidence risks an error of inclusion. It is a balancing act.

63

I believe my responsibility is to state the most likely conclusion based on the preponderance of the evidence I have, even though often that conclusion may not be proven beyond the shadow of a doubt. To be too insistent on solid proof before listing a town as sundown risks an error of exclusion. To list a town as sundown with inadequate evidence risks an error of inclusion. It is a balancing act.

We have seen that evidence of a town’s sundown practices can come from oral history, newspapers of the time, local histories, newspaper articles written today based on some of the above, and various other sources, confirmed with census data. Getting such evidence usually requires on-site research, contact with current or former residents, and/or published secondary sources in a library. For most towns, this research is doable and not too difficult: most on-site inquiries quickly reveal whether an all-white town is intentional. My biggest problem was that I soon discovered that most of the thousands of all-white towns in the North had not always been all-white and probably became all-white on purpose. I therefore had far more towns to check out than I could possibly manage.

How have sundown towns managed to stay so white for so long? Their whiteness was enforced, and the next chapter tells how.

[1]

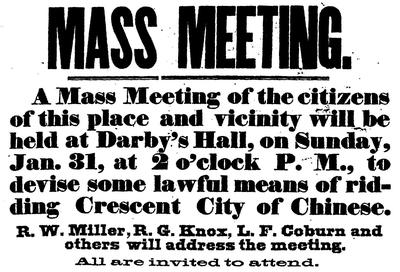

Chinese Americans had lived in Crescent City, California, near the Oregon line, since at least the 1870s. The meeting advertised on this broadside was the first of a series lasting until mid-March, 1886. Eventually “lawful” was dropped and a mob forced the Chinese to depart on three sailing vessels bound for San Francisco. Whites in Humboldt County, the next county south, had already expelled 320 Chinese Americans from Eureka in 1885. In 1886 they drove Chinese from Arcata, Ferndale, Fortuna, Rohnerville, and Trinidad.

[2]

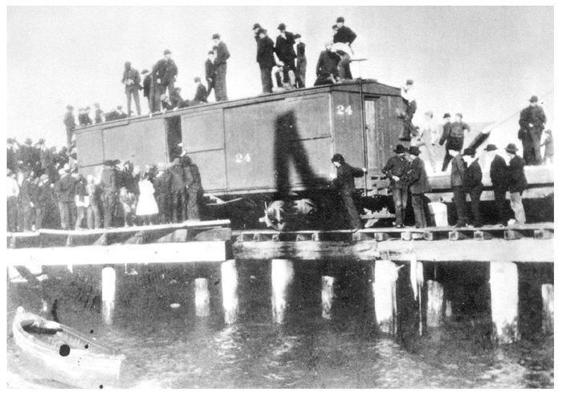

In 1906 they finished the job, loading these cannery workers onto boxcars, leaving their belongings behind. No Chinese returned to Humboldt Bay until the 1950s.

(Notes for this Portfolio section begin on page 523; photography credits begin on page 525.)

Chinese Americans had lived in Crescent City, California, near the Oregon line, since at least the 1870s. The meeting advertised on this broadside was the first of a series lasting until mid-March, 1886. Eventually “lawful” was dropped and a mob forced the Chinese to depart on three sailing vessels bound for San Francisco. Whites in Humboldt County, the next county south, had already expelled 320 Chinese Americans from Eureka in 1885. In 1886 they drove Chinese from Arcata, Ferndale, Fortuna, Rohnerville, and Trinidad.

[2]

In 1906 they finished the job, loading these cannery workers onto boxcars, leaving their belongings behind. No Chinese returned to Humboldt Bay until the 1950s.

(Notes for this Portfolio section begin on page 523; photography credits begin on page 525.)

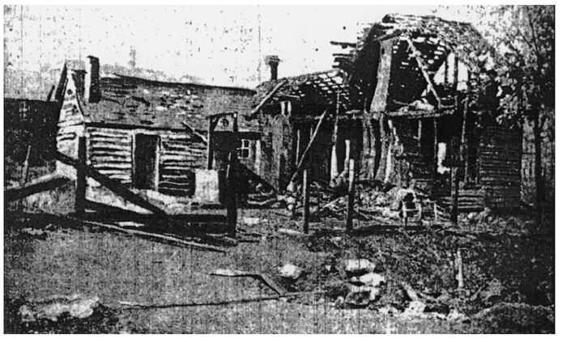

In an all-night riot in August, 1901, white residents of Pierce City, Missouri, hanged a young black man alleged to have murdered a white woman, killed his grandfather, looted the armory, and used its Springfield rifles to attack the black community. African Americans fired back but were outgunned.

[3]

The mob then burned several homes including this one, Emma Carter’s, incinerating at least two African Americans inside. At 2 A.M., Pierce City’s 200 black residents ran for their lives. They found no refuge in the nearest town, Monett, because in 1894 it had expelled its blacks in a similar frenzy and hung a sign, “Nigger, Don’t Let The Sun Go Down.”

[4]

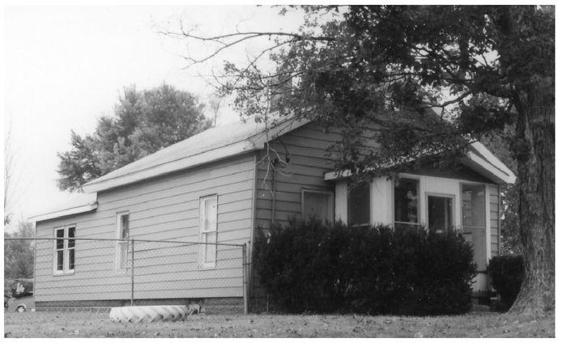

The house below stands in the “Black Hills,” home to African Americans in Pinckneyville, Illinois, until they were driven out around 1928. A woman born across the street in 1947 recalls being teased in school “for living in niggertown.” This house was formerly the black school.

[3]

The mob then burned several homes including this one, Emma Carter’s, incinerating at least two African Americans inside. At 2 A.M., Pierce City’s 200 black residents ran for their lives. They found no refuge in the nearest town, Monett, because in 1894 it had expelled its blacks in a similar frenzy and hung a sign, “Nigger, Don’t Let The Sun Go Down.”

[4]

The house below stands in the “Black Hills,” home to African Americans in Pinckneyville, Illinois, until they were driven out around 1928. A woman born across the street in 1947 recalls being teased in school “for living in niggertown.” This house was formerly the black school.

[5]

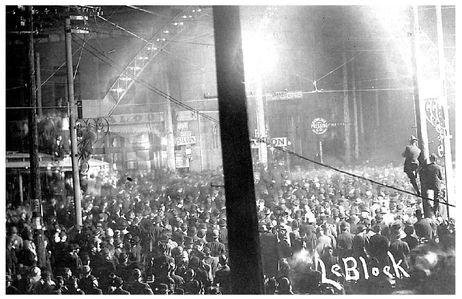

Will James, who had been arrested for the murder of Anna Pelley, has just been hanged under this brilliantly illuminated double arch that was the pride of downtown Cairo, Illinois, on November 11, 1909. Among the thousands of spectators were some from Anna, 30 miles north, where Pelley had grown up. Afterward, they returned home and drove all African Americans out of Anna.

[6]

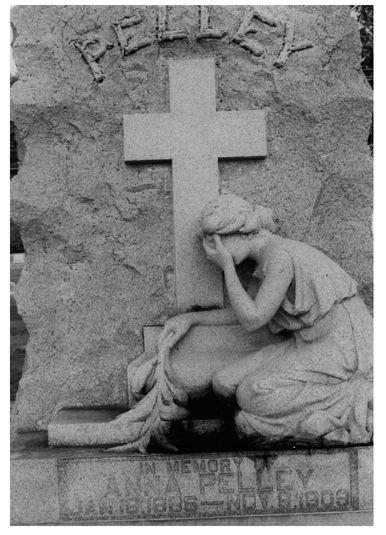

Public subscription then paid for this striking granite tombstone commemorating Pelley. Adolescents in Anna still pay their respects at this site, a rite that helps maintain Anna as a sundown town.

Will James, who had been arrested for the murder of Anna Pelley, has just been hanged under this brilliantly illuminated double arch that was the pride of downtown Cairo, Illinois, on November 11, 1909. Among the thousands of spectators were some from Anna, 30 miles north, where Pelley had grown up. Afterward, they returned home and drove all African Americans out of Anna.

[6]

Public subscription then paid for this striking granite tombstone commemorating Pelley. Adolescents in Anna still pay their respects at this site, a rite that helps maintain Anna as a sundown town.

Other books

Wishful Thinking by Alexandra Bullen

1 by Gay street, so Jane always thought, did not live up to its name.

Tanner's War by Amber Morgan

Moonshine by Moira Rogers

The Pirate Organization: Lessons From the Fringes of Capitalism by Rodolphe Durand, Jean-Philippe Vergne

Tropical Storm by Graham, Stefanie

Guardian Bears: Lucas by Leslie Chase

Lawe's Justice by Leigh, Lora

Love Under Three Titans by Cara Covington

Vacation to Die For by Josie Brown