Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (42 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

9.1Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

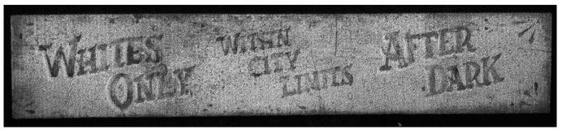

Eyewitnesses tell of sundown signs in more than 150 communities in 31 states. Most read, “Nigger, Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On You In ___.” Some came in series, like the old Burma-Shave signs: “Nigger, If You Can Read,” “You’d Better Run,” “If You Can’t Read,” “You’d Better Run Anyway.” Despite considerable legwork, I have not located a single photo of such a sign. Local librarians laugh when I ask if they saved theirs or a photo of it: “Why would we do that?”

[7]

James Allen, who assembled a famous exhibit of lynching postcards, bought this sign around 1985; its only provenance is “from Connecticut.”

[8]

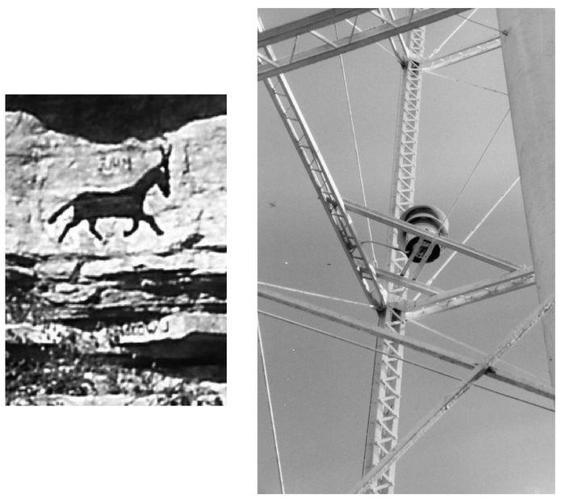

At left is a sign still extant, a black mule, used by residents of sundown towns in Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee to warn African Americans to “get their black ass” outside the city limits by sundown. Margaret Alam photographed this example just west of Liberty, Tennessee, in 2003. Other towns used sirens.

[9]

In 1914, Villa Grove, Illinois, put up this water tower. Sometime thereafter, the town mounted a siren on it that sounded at 6 P.M. to warn African Americans to get beyond the city limits, until about 1998.

[7]

James Allen, who assembled a famous exhibit of lynching postcards, bought this sign around 1985; its only provenance is “from Connecticut.”

[8]

At left is a sign still extant, a black mule, used by residents of sundown towns in Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee to warn African Americans to “get their black ass” outside the city limits by sundown. Margaret Alam photographed this example just west of Liberty, Tennessee, in 2003. Other towns used sirens.

[9]

In 1914, Villa Grove, Illinois, put up this water tower. Sometime thereafter, the town mounted a siren on it that sounded at 6 P.M. to warn African Americans to get beyond the city limits, until about 1998.

[10]

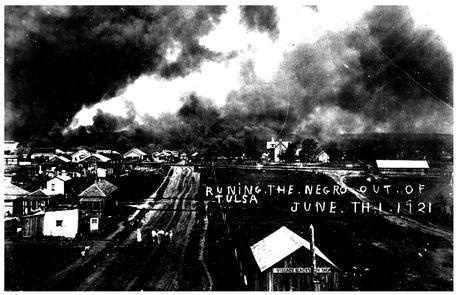

On June 1, 1921, whites tried to make Tulsa, Oklahoma, a sundown town. As part of the attack, deputized white men raided a munitions dump, commandeered five airplanes, and dropped dynamite onto the black community, making it the only place in the contiguous United States ever to undergo aerial bombardment. Like efforts to expel blacks from other large cities, the Tulsa mob failed; the job was simply too large.

On June 1, 1921, whites tried to make Tulsa, Oklahoma, a sundown town. As part of the attack, deputized white men raided a munitions dump, commandeered five airplanes, and dropped dynamite onto the black community, making it the only place in the contiguous United States ever to undergo aerial bombardment. Like efforts to expel blacks from other large cities, the Tulsa mob failed; the job was simply too large.

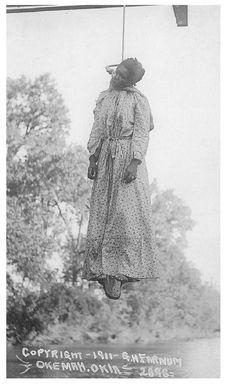

Earlier, in May, 1911, the teenage son of Laura Nelson, who lived near Boley, Oklahoma, a black town, killed a deputy who was searching their cabin for stolen meat. His mother, trying to protect him, claimed she did it.

[11]

“Her innocence was determined weeks before the lynching,” according to James Allen, who collected this postcard of the lynching. Nevertheless, a white mob from Okemah, a sundown town ten miles east of Boley, hanged Nelson and her son from this bridge spanning the North Canadian River. Residents then stayed up all night to fend off an imagined mob, said to be coming from Boley to sack Okemah. Similar fears prompted similar mobilizations in sundown suburbs during urban ghetto riots in the 1960s.

[11]

“Her innocence was determined weeks before the lynching,” according to James Allen, who collected this postcard of the lynching. Nevertheless, a white mob from Okemah, a sundown town ten miles east of Boley, hanged Nelson and her son from this bridge spanning the North Canadian River. Residents then stayed up all night to fend off an imagined mob, said to be coming from Boley to sack Okemah. Similar fears prompted similar mobilizations in sundown suburbs during urban ghetto riots in the 1960s.

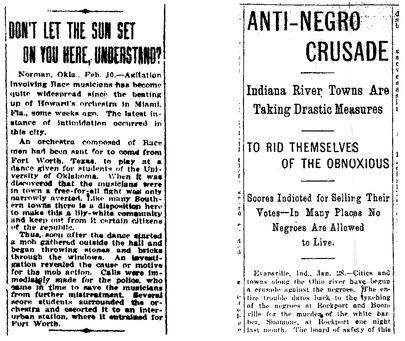

University of Oklahoma students invited a black orchestra to play for their dance, but citizens of Norman intervened because the musicians violated Norman’s sundown rule.

[12]

This 1922 story in the

Chicago Defender

uses “Race” where we would use “black.”

[13]

At right, datelined Evansville, a report tells of a wave of anti-black actions in southwestern Indiana in 1901, triggered by “the lynching of the Negroes at Rockport and Boonville for the murder of the white barber.” Only contagion can explain how the murder of one barber could prompt three lynchings in Rockport, one in Boonville, and “vigilance committees” to drive African Americans from at least five other towns.

[14]

The full headline below is “White Men Shoot Up Church Excursioners.” Black motorists stranded in sundown towns have always been in danger, no matter their circumstances. In August 1940, a church group in Charleston, South Carolina, hired a bus to attend an event. On their way home, it broke down in the little town of Bonneau. While they were waiting for a replacement bus, sixteen white men came on the scene and ordered them to “get out [of] here right quick. We don’t allow no d—n n—rs ’round here after sundown.” They then opened fire on the parishioners with shotguns, causing them to flee into nearby woods.

[12]

This 1922 story in the

Chicago Defender

uses “Race” where we would use “black.”

[13]

At right, datelined Evansville, a report tells of a wave of anti-black actions in southwestern Indiana in 1901, triggered by “the lynching of the Negroes at Rockport and Boonville for the murder of the white barber.” Only contagion can explain how the murder of one barber could prompt three lynchings in Rockport, one in Boonville, and “vigilance committees” to drive African Americans from at least five other towns.

[14]

The full headline below is “White Men Shoot Up Church Excursioners.” Black motorists stranded in sundown towns have always been in danger, no matter their circumstances. In August 1940, a church group in Charleston, South Carolina, hired a bus to attend an event. On their way home, it broke down in the little town of Bonneau. While they were waiting for a replacement bus, sixteen white men came on the scene and ordered them to “get out [of] here right quick. We don’t allow no d—n n—rs ’round here after sundown.” They then opened fire on the parishioners with shotguns, causing them to flee into nearby woods.

[15]

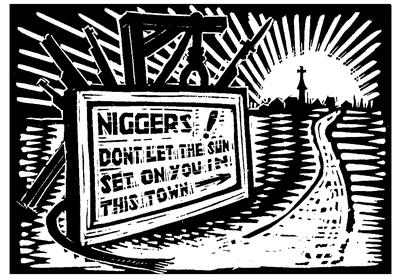

This 1935 linoleum cut by Lin Shi Khan is part of a collection titled

Scottsboro Alabama

. Scottsboro was not a sundown town, but most towns in the nearby Sand Mountains were.

[16]

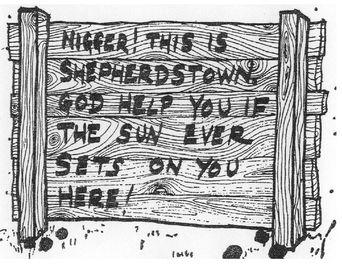

For his 1973 novel

Breakfast of Champions,

Kurt Vonnegut drew this Indiana sundown sign. A character relates that when a black family got off a boxcar in “Shepherdstown” during the Depression, perhaps not seeing the sign, and sought shelter in an empty shack for the night, a mob got the man and “sawed him in two on the top strand of a barbed-wire fence.” Vonnegut grew up in Indianapolis, surrounded by sundown towns. His is the only visual representation I have found of a sundown sign in the Midwest or West, even though I have evidence of such signs in more than 100 towns in those regions and suspect they stood in more than 1000.

This 1935 linoleum cut by Lin Shi Khan is part of a collection titled

Scottsboro Alabama

. Scottsboro was not a sundown town, but most towns in the nearby Sand Mountains were.

[16]

For his 1973 novel

Breakfast of Champions,

Kurt Vonnegut drew this Indiana sundown sign. A character relates that when a black family got off a boxcar in “Shepherdstown” during the Depression, perhaps not seeing the sign, and sought shelter in an empty shack for the night, a mob got the man and “sawed him in two on the top strand of a barbed-wire fence.” Vonnegut grew up in Indianapolis, surrounded by sundown towns. His is the only visual representation I have found of a sundown sign in the Midwest or West, even though I have evidence of such signs in more than 100 towns in those regions and suspect they stood in more than 1000.

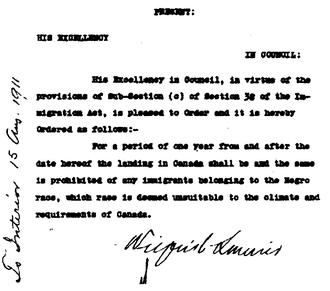

The Nadir reached Canada, too. Canada had welcomed fugitive slaves, but by 1910, whites in Canada’s western provinces, facing a trickle of African Americans fleeing racism in the Plains states, protested to Ottawa.

[17]

In 1911, the government replied by prohibiting “any immigrants belonging to the Negro race.” The prohibition was repealed two months later, but Canada did send agents to Oklahoma to discourage black immigrants.

[18]

Some riots that drove African Americans from small towns left documentary hints, such as the telegram below. In Missouri, a black Civilian Conservation Corps unit was scheduled to work in Lawrence County in 1935, prompting this telegram to Gov. Guy Park. I think the “riot and blood shed several years ago” alludes to a riot in Mt. Vernon, Missouri, in 1906, but it may refer to a more recent event. The telegram worked: the camp was moved; and Lawrence County’s black population declined to just 21 by 1950.

[17]

In 1911, the government replied by prohibiting “any immigrants belonging to the Negro race.” The prohibition was repealed two months later, but Canada did send agents to Oklahoma to discourage black immigrants.

[18]

Some riots that drove African Americans from small towns left documentary hints, such as the telegram below. In Missouri, a black Civilian Conservation Corps unit was scheduled to work in Lawrence County in 1935, prompting this telegram to Gov. Guy Park. I think the “riot and blood shed several years ago” alludes to a riot in Mt. Vernon, Missouri, in 1906, but it may refer to a more recent event. The telegram worked: the camp was moved; and Lawrence County’s black population declined to just 21 by 1950.

Other books

The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller

Evil That Men Do by Hugh Pentecost

The Falling Kind by Kennedy, Randileigh

Facing It by Linda Winfree

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) by Mark Twain

Breaker by Richard Thomas

This Savage Song by Victoria Schwab

Fear the Heart (Werelock Evolution Book 2) by Hettie Ivers

PullMyHair by Kimberly Kaye Terry

Step Alien: A Sci-Fi Alien Romance (Reestrian Mates Book 1) by Sue Mercury