Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (44 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

2.91Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

[27]

In the mid-1920s, Mena, county seat of Polk County, Arkansas, competed for white residents and tourists by advertising what it had and what it did

not

have. The sentiment hardly died in the 1920s. A 1980 article, “The Real Polk County,” began, “It is not an uncommon experience in Polk County to hear a newcomer remark that he chose to move here because of ‘low taxes and no niggers.’ ”

[28]

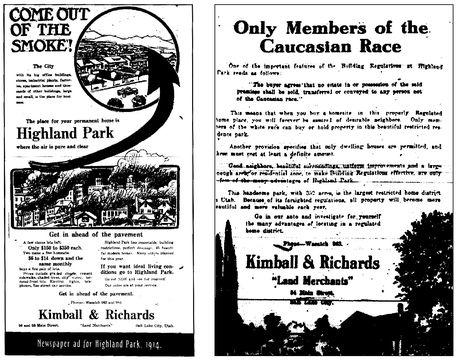

Suburbs followed suit. In 1914, developers of Highland Park near Salt Lake City appealed to would-be homebuyers to leave behind the problems of the city, like its smoke. By 1919, the appeal had become racial. Even today, the most prestigious suburbs are often those with the lowest proportions of African Americans.

In the mid-1920s, Mena, county seat of Polk County, Arkansas, competed for white residents and tourists by advertising what it had and what it did

not

have. The sentiment hardly died in the 1920s. A 1980 article, “The Real Polk County,” began, “It is not an uncommon experience in Polk County to hear a newcomer remark that he chose to move here because of ‘low taxes and no niggers.’ ”

[28]

Suburbs followed suit. In 1914, developers of Highland Park near Salt Lake City appealed to would-be homebuyers to leave behind the problems of the city, like its smoke. By 1919, the appeal had become racial. Even today, the most prestigious suburbs are often those with the lowest proportions of African Americans.

In 1948, a Federal Housing Administration commissioner boasted that “the FHA has never insured a housing project of mixed occupancy.”

[29]

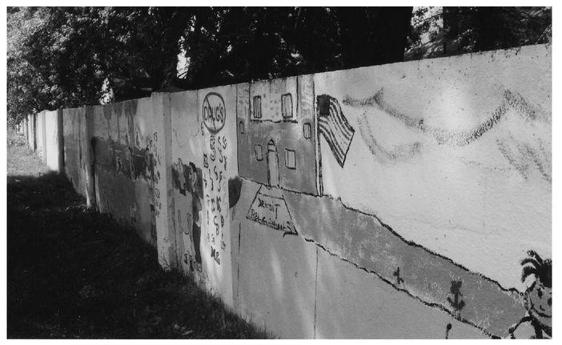

This six-foot concrete block wall was built to separate a white neighborhood from an interracial one in northwestern Detroit so homes on the white side could qualify for FHA loan guarantees. It runs for half a mile, from the city limits to a park. Today African Americans live on both sides, but the wall still divides the neighborhood in two and serves as a reminder on the landscape that federal policies explicitly favored segregated neighborhoods until 1968.

[30]

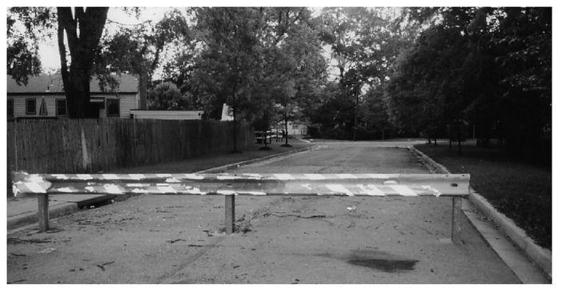

A street barrier marks the border between North Brentwood, a black community, and Brentwood, Maryland, a sundown suburb into the 1960s. Struck by the absence of any social class difference between homes on both sides of the barrier, I asked Denise Thomas, who grew up in North Brentwood in the 1950s, “What kept people from North Brentwood from crossing that line?” “KKK!” was her heartfelt answer. By that she meant not only the Klan, which burned crosses in North Brentwood, but also many other instances of harassment. “They threw things at us, called us ‘nigger,’ ‘spook,’ all kind of things.” “The white children?” I asked. “Uh-huh,” she affirmed, “and the adults.”

[29]

This six-foot concrete block wall was built to separate a white neighborhood from an interracial one in northwestern Detroit so homes on the white side could qualify for FHA loan guarantees. It runs for half a mile, from the city limits to a park. Today African Americans live on both sides, but the wall still divides the neighborhood in two and serves as a reminder on the landscape that federal policies explicitly favored segregated neighborhoods until 1968.

[30]

A street barrier marks the border between North Brentwood, a black community, and Brentwood, Maryland, a sundown suburb into the 1960s. Struck by the absence of any social class difference between homes on both sides of the barrier, I asked Denise Thomas, who grew up in North Brentwood in the 1950s, “What kept people from North Brentwood from crossing that line?” “KKK!” was her heartfelt answer. By that she meant not only the Klan, which burned crosses in North Brentwood, but also many other instances of harassment. “They threw things at us, called us ‘nigger,’ ‘spook,’ all kind of things.” “The white children?” I asked. “Uh-huh,” she affirmed, “and the adults.”

[31]

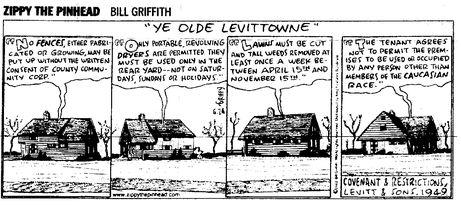

In 2002, Bill Griffith’s comic strip “Zippy the Pinhead” quoted the regulations set up by Levitt & Sons for the first Levittown. No one made light of them in the 1950s when the three Levittowns were going up. It would not have been cause for amusement or concern then, just everyday life, for Levitt & Sons was by far the largest single homebuilder in post-World War II America. If regulations didn’t work, violence usually did.

[32]

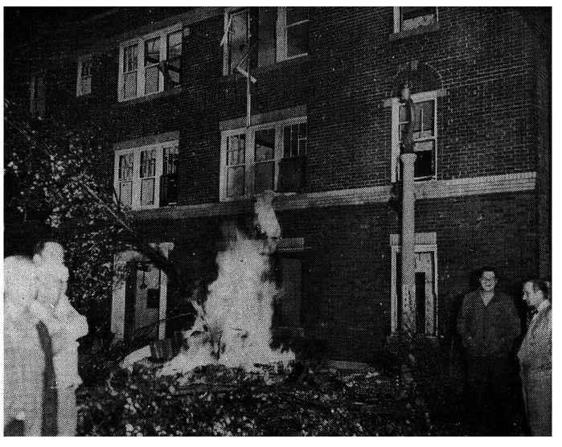

In July, 1951, a mob rioted for three days to keep a black bus driver, Harvey Clark, and his family from occupying an apartment in this building in Cicero, a sundown suburb of Chicago. In this photo, whites have thrown the Clarks’ furniture and other possessions into the courtyard of the complex and set it on fire. Eventually a grand jury indicted the owner, Camille DeRose, not the mob! Cicero remained all white until the 1990s.

In 2002, Bill Griffith’s comic strip “Zippy the Pinhead” quoted the regulations set up by Levitt & Sons for the first Levittown. No one made light of them in the 1950s when the three Levittowns were going up. It would not have been cause for amusement or concern then, just everyday life, for Levitt & Sons was by far the largest single homebuilder in post-World War II America. If regulations didn’t work, violence usually did.

[32]

In July, 1951, a mob rioted for three days to keep a black bus driver, Harvey Clark, and his family from occupying an apartment in this building in Cicero, a sundown suburb of Chicago. In this photo, whites have thrown the Clarks’ furniture and other possessions into the courtyard of the complex and set it on fire. Eventually a grand jury indicted the owner, Camille DeRose, not the mob! Cicero remained all white until the 1990s.

[33]

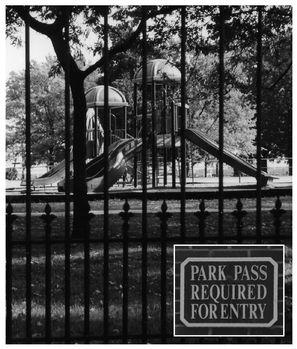

According to historian Kenneth Jackson, “the most conspicuous city-suburban contrast in the U. S. runs along Detroit’s Alter Road” separating Detroit from Grosse Pointe. Just across the line is this park, but Detroit children cannot play on its playground equipment. “It’s not fair,” observed Reginald Pickins, who grew up less than 50 feet from the border. “Why should we have to have passes to go into their parks? They don’t need passes for ours.”

According to historian Kenneth Jackson, “the most conspicuous city-suburban contrast in the U. S. runs along Detroit’s Alter Road” separating Detroit from Grosse Pointe. Just across the line is this park, but Detroit children cannot play on its playground equipment. “It’s not fair,” observed Reginald Pickins, who grew up less than 50 feet from the border. “Why should we have to have passes to go into their parks? They don’t need passes for ours.”

[34]

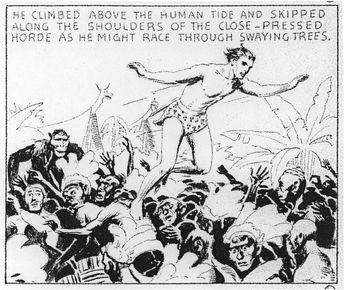

Tarzan, the white man who mastered the African jungle, was born in one sundown suburb, Oak Park, Illinois, where his creator, Edgar Rice Burroughs, wrote the first Tarzan books, and gave birth to another sundown town when Burroughs used the proceeds from his novels, movies, and long-running comic strip to create Tarzana, California. In this 1934 strip “the island savages” flee “in terror” from jungle creatures, “believing the beasts were demons conjured up by Tarzan.” The strip literally shows white supremacy: Tarzan is more intelligent, courageous, and moral than the black “savages,” whom he literally walks all over.

Tarzan, the white man who mastered the African jungle, was born in one sundown suburb, Oak Park, Illinois, where his creator, Edgar Rice Burroughs, wrote the first Tarzan books, and gave birth to another sundown town when Burroughs used the proceeds from his novels, movies, and long-running comic strip to create Tarzana, California. In this 1934 strip “the island savages” flee “in terror” from jungle creatures, “believing the beasts were demons conjured up by Tarzan.” The strip literally shows white supremacy: Tarzan is more intelligent, courageous, and moral than the black “savages,” whom he literally walks all over.

PART IV

Sundown Towns in Operation

9

Enforcement

It was well known any black people arriving in town were not to venture beyond the block the bus stop or train station were in. My father even remembers a group of three teenage boys bragging that they had seen the “niggers” from the bus stop walking down the street and stopped them and told them they were not allowed to leave the bus stop. Another individual who is slightly older than my parents and lived in Effingham said the police would patrol the train station and bus stop to ensure black people did not leave them. She stated that she was unsure whether this was due to prejudice on the part of police, or to protect the black people from the individuals residing in Effingham.—Michelle Tate, summarizing oral history collected in and around Effingham, Illinois, fall 2002

1

A

STRIKING CHARACTERISTIC of sundown towns is their durability. Once a town or suburb defines itself “white,” it usually stays white for decades. Yet all-white towns are inherently unstable. Americans are always on the move, going to new places, and so are African Americans. Remaining white in census after census is not achieved easily. How is this whiteness maintained?

STRIKING CHARACTERISTIC of sundown towns is their durability. Once a town or suburb defines itself “white,” it usually stays white for decades. Yet all-white towns are inherently unstable. Americans are always on the move, going to new places, and so are African Americans. Remaining white in census after census is not achieved easily. How is this whiteness maintained?

Residents have used a variety of invisible enforcement mechanisms that become visible whenever an African American comes to town or “threatens” to come to town. The

Illinois State Register

stated the basic method of enforcement in 1908 in the aftermath of the Springfield riot: “A Negro is an unwelcome visitor and is soon informed he must not remain in the town.”

2

But there are many variations in how this message has been delivered. We shall begin with the cruder methods relied upon by independent sundown towns, then “progress” to the more sophisticated and subtler measures that sundown suburbs have taken to remain overwhelmingly white—but we must note that even elite sundown suburbs have resorted to violence on occasion.

The Inadvertent VisitorIllinois State Register

stated the basic method of enforcement in 1908 in the aftermath of the Springfield riot: “A Negro is an unwelcome visitor and is soon informed he must not remain in the town.”

2

But there are many variations in how this message has been delivered. We shall begin with the cruder methods relied upon by independent sundown towns, then “progress” to the more sophisticated and subtler measures that sundown suburbs have taken to remain overwhelmingly white—but we must note that even elite sundown suburbs have resorted to violence on occasion.

From time to time, an African American person or family have found themselves in a sundown town completely by accident. Immediately they were suspect, and usually they were in danger. Sundown towns rarely tolerated African American visitors who happened within their gates when night fell. Even if they were there inadvertently—even if they had no knowledge of the town’s tradition beforehand—whites viewed them as having no right to be in “our town” after dark and often replied with behavior that was truly vile, yet in the service of “good” as defined by the community.

Hiking from town to town was a common mode of travel before the 1920s and grew common again during the Great Depression. Walking was the most exposed form of transit through a sundown town. As we saw previously, whites in Comanche County, Texas, drove out their African Americans in 1886. Local historian Billy Bob Lightfoot tells of an African American who made a bet some years later that he could walk across the county, but “was never seen again after he stopped at a farm near De Leon for a drink of water.” He made less than eight miles before whites killed him.

3

3

Other books

The View from Mount Joy by Lorna Landvik

The Ranger (Book 1) by E.A. Whitehead

The Bad Boys' Virgin Temptress (The Law Castle Bad Boys) by Crescent, Sam

Two Bears For Christmas by Tianna Xander

Meg's Moment by Amy Johnson

Third Chance by Ann Mayburn, Julie Naughton

Drowned Ammet by Diana Wynne Jones

A Knight of Temptation by Evie North

The Shadow Man by F. M. Parker

Psion Alpha by Jacob Gowans