Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (43 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

12.63Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

[19]

After Comanche and Hamilton counties in Texas drove out their African Americans in 1886, Alec and Mourn Gentry were the only two who “have been permitted to reside in this section,” in the words of the 1958 Hamilton County centennial history. “ ‘Uncle Alec’ and ‘Aunt Mourn’ lived to a ripe old age.... They were Gentry Negroes, and former slaves of Capt. F. B. Gentry. . . .” They were no one’s uncle or aunt in Hamilton County, of course; these are terms of quasi-respect whites used during the Nadir for older African Americans to avoid “Mr.” or “Mrs.” (Aunt Jemima Syrup and Uncle Ben’s Rice linger as vestiges of this practice.) Gentry’s pose shows that he knows his place, essential to his well-being in a sundown county.

After Comanche and Hamilton counties in Texas drove out their African Americans in 1886, Alec and Mourn Gentry were the only two who “have been permitted to reside in this section,” in the words of the 1958 Hamilton County centennial history. “ ‘Uncle Alec’ and ‘Aunt Mourn’ lived to a ripe old age.... They were Gentry Negroes, and former slaves of Capt. F. B. Gentry. . . .” They were no one’s uncle or aunt in Hamilton County, of course; these are terms of quasi-respect whites used during the Nadir for older African Americans to avoid “Mr.” or “Mrs.” (Aunt Jemima Syrup and Uncle Ben’s Rice linger as vestiges of this practice.) Gentry’s pose shows that he knows his place, essential to his well-being in a sundown county.

[20]

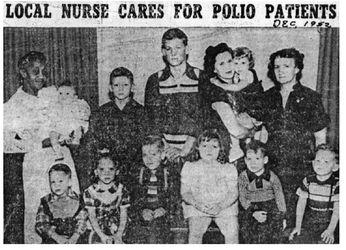

Elizabeth Davis and her son were the only exceptions allowed in Casey, Illinois, until well after her death in 1963 at 76. She was a nurse-midwife, and this 1952 newspaper photo was accompanied by a poem, “A Tribute to Miss Davis,” showing Casey’s respect for her. At the same time, Davis was known everywhere as “Nigger Liz,” and Casey at one time boasted a sundown sign at the west edge of town.

Elizabeth Davis and her son were the only exceptions allowed in Casey, Illinois, until well after her death in 1963 at 76. She was a nurse-midwife, and this 1952 newspaper photo was accompanied by a poem, “A Tribute to Miss Davis,” showing Casey’s respect for her. At the same time, Davis was known everywhere as “Nigger Liz,” and Casey at one time boasted a sundown sign at the west edge of town.

Between 1920 and 1928, KKK rallies were so huge that they remain the biggest single meetings many towns have ever seen.

[21]

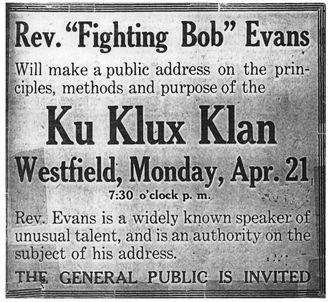

This lecture in Westfield, Illinois, in 1924 was an example; a later article told of a “Big Demonstration” planned for “Klan Day” at the Clark County Fair in neighboring Martinsville. Predicted the newspaper, “As we know that a Klan gathering draws spectators like jam draws flies, we can expect that Martinsville on that date will witness the largest gathering of people ever assembled in Clark County.” Yet many of these towns—including Martinsville and Westfield—were sundown towns that had already gotten rid of their African Americans and had no Jews and few Catholics, so in a sense there was nothing left for the Klan to do.

[22]

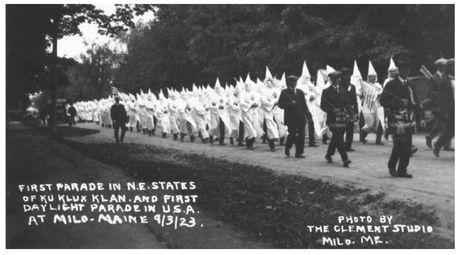

Similarly, African Americans hardly existed in most of Maine in the 1920s—sometimes owing to sundown policies—yet Milo boasted the “first daylight [Klan] parade in U.S.A.” In the 2000 census, Milo finally showed its first African American household. Martinsville and Westfield still have none.

[21]

This lecture in Westfield, Illinois, in 1924 was an example; a later article told of a “Big Demonstration” planned for “Klan Day” at the Clark County Fair in neighboring Martinsville. Predicted the newspaper, “As we know that a Klan gathering draws spectators like jam draws flies, we can expect that Martinsville on that date will witness the largest gathering of people ever assembled in Clark County.” Yet many of these towns—including Martinsville and Westfield—were sundown towns that had already gotten rid of their African Americans and had no Jews and few Catholics, so in a sense there was nothing left for the Klan to do.

[22]

Similarly, African Americans hardly existed in most of Maine in the 1920s—sometimes owing to sundown policies—yet Milo boasted the “first daylight [Klan] parade in U.S.A.” In the 2000 census, Milo finally showed its first African American household. Martinsville and Westfield still have none.

[23]

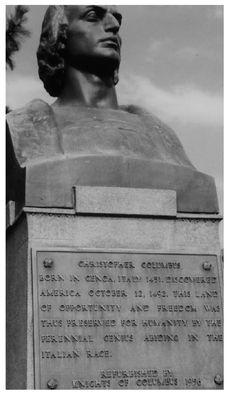

Audiences cackle at the last line on this bust of Christopher Columbus. They “know” Italians are not a race. It seems obvious now that there are only three races (Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid), or four (Australoid), or five (American Indian). This was not Hitler’s understanding, who “knew” Jews to be a race; nor was it Italian Americans’ in 1920 when they erected this bust at the Indiana State Capitol. At that time eugenicists ranked Greeks, Italians, and Slavs

racially

inferior and aimed the 1924 immigration restrictions largely at them. By 1940, however, these races became one—“white.” Jews, Armenians, and Turks took just a little longer. Now “white” seems to incorporate Latin and Asian Americans, which most sundown towns have long admitted. In 1960, Dearborn, Michigan, called Arabs “white population born in Asia” and Mexicans “white population born in Mexico” in official documents, thus remaining “all white” as a city. Sundown town policy now seems to be: all groups are fine except blacks.

Audiences cackle at the last line on this bust of Christopher Columbus. They “know” Italians are not a race. It seems obvious now that there are only three races (Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid), or four (Australoid), or five (American Indian). This was not Hitler’s understanding, who “knew” Jews to be a race; nor was it Italian Americans’ in 1920 when they erected this bust at the Indiana State Capitol. At that time eugenicists ranked Greeks, Italians, and Slavs

racially

inferior and aimed the 1924 immigration restrictions largely at them. By 1940, however, these races became one—“white.” Jews, Armenians, and Turks took just a little longer. Now “white” seems to incorporate Latin and Asian Americans, which most sundown towns have long admitted. In 1960, Dearborn, Michigan, called Arabs “white population born in Asia” and Mexicans “white population born in Mexico” in official documents, thus remaining “all white” as a city. Sundown town policy now seems to be: all groups are fine except blacks.

[24]

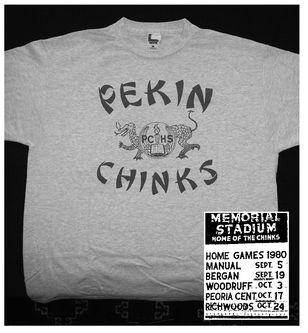

Although Pekin, Illinois, called its high school athletic teams “Chinks,” referencing Peking (now Beijing) China, it insisted this was a compliment and allowed Chinese as residents. The name changed in 1980, but even today many graduates defend the old name. “I can’t wait to get Chinks memorabilia, and my kids would love to see it too,” stated one alum in 2000. I bought this new T-shirt in Pekin in 2002. It shows visually the bluntly racist rhetoric many residents of sundown towns routinely employ.

Although Pekin, Illinois, called its high school athletic teams “Chinks,” referencing Peking (now Beijing) China, it insisted this was a compliment and allowed Chinese as residents. The name changed in 1980, but even today many graduates defend the old name. “I can’t wait to get Chinks memorabilia, and my kids would love to see it too,” stated one alum in 2000. I bought this new T-shirt in Pekin in 2002. It shows visually the bluntly racist rhetoric many residents of sundown towns routinely employ.

[25]

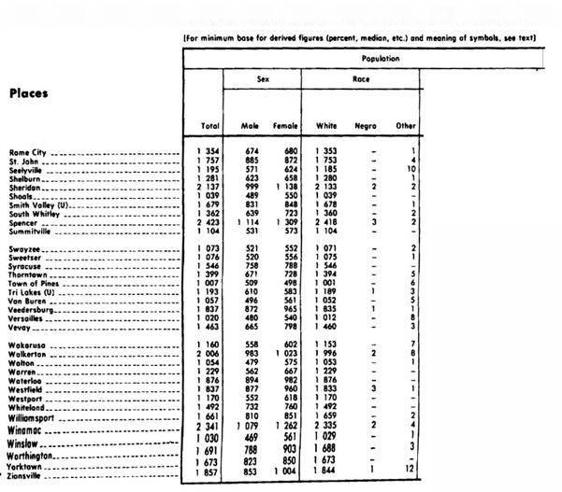

This page from the 1970 census shows how widespread all-white towns—probably sundown towns—have been in Indiana. Twenty-six of these 34 had not a single black resident, and bearing in mind that sundown towns often allowed an exception for one black family, we cannot be sure that

any

of the 34 admitted African Americans. Indiana had twenty times as many African Americans as “Others” in 1970, yet Others lived much more widely.

[26]

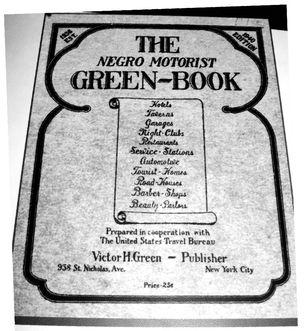

To avoid sundown towns and negotiate travel without danger or embarrassment, African Americans produced guidebooks such as

Travelguide: Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation

and this

Negro Motorist Green Book.

They listed hotels, restaurants, auto repair shops, etc., that would serve black travelers.

This page from the 1970 census shows how widespread all-white towns—probably sundown towns—have been in Indiana. Twenty-six of these 34 had not a single black resident, and bearing in mind that sundown towns often allowed an exception for one black family, we cannot be sure that

any

of the 34 admitted African Americans. Indiana had twenty times as many African Americans as “Others” in 1970, yet Others lived much more widely.

[26]

To avoid sundown towns and negotiate travel without danger or embarrassment, African Americans produced guidebooks such as

Travelguide: Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation

and this

Negro Motorist Green Book.

They listed hotels, restaurants, auto repair shops, etc., that would serve black travelers.

Other books

Wrangler by Dani Wyatt

Chasing Temptation by Lane, Payton

The Sheikh's Amulet (Sheikh's Wedding Bet Series Book 3) by Leslie North

Companions: Fifty Years of Doctor Who Assistants by Andy Frankham-Allen

Desire (#5) by Cox, Carrie

The Vanishing Half: A Novel by Brit Bennett

False Witness by Dexter Dias

The Detention Club by David Yoo

Redneck Nation by Michael Graham

Beau Jest by James Sherman