The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less (28 page)

Read The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less Online

Authors: Richard Koch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Psychology, #Self Help, #Business, #Philosophy

• The mentor should be as senior as possible or, even better, relatively junior but clearly destined for the top. The best mentors are extremely able and ambitious.

It may seem strange to say that relationships with mentors should be reciprocal, since inevitably the mentor will have more to offer than the mentee. But mentors must be rewarded or else they will lose interest. The mentee must provide fresh ideas, mental stimulation, enthusiasm, hard work, knowledge of new technologies, or some other attribute of value to the mentor. Wise mentors very often use younger allies to keep them up to date with emerging trends and potential opportunities or threats that may not be apparent from the top.

Relationships with peers

With peers, you are very often spoilt for choice. There are many potential allies. But remember that you have only two or three slots to fill. Be very selective. Make a list of all potential allies who have the “five ingredients” or potential for them. Pick the two or three from the list who you believe will be the most successful. Then work hard at making them allies.

Relationships where you are the mentor

Do not neglect these. You are likely to get the most out of your one or two mentees if they work for you, preferably for quite a long period of time.

MULTIPLE ALLIANCES

Alliances very often build up into webs or networks, where many of the same people have relationships with each other. These networks can become very powerful, or at least seem so from the outside. They are often great fun.

But do not get carried away, smug in the knowledge that you are “in with the in crowd.” You may just be a fringe player. Don’t forget that all true and valuable relationships are bilateral. If you have a strong alliance with both X and Y and they have one between each other, that is excellent. Lenin said that a chain is as strong as its weakest link. However strong the relationships between X and Y, the ones that really matter for you are yours with X and yours with Y.

CONCLUSION

For both personal and professional relationships, fewer and deeper is better than more and less deep. One relationship is not as good as another. Seriously flawed relationships, when you spend a lot of time together but the result is unsatisfying, should be terminated as soon as possible. Bad relationships drive out good. There is a limited number of slots for relationships; don’t use up the slots too early or on low-quality relationships.

Choose with care. Then build with commitment.

A FORK IN THE BOOK

We have now reached an optional fork in this book’s progress. The next two chapters (13 and 14) are, respectively, for those who want to know how to advance their careers or multiply their money. Readers for whom these are not important concerns should advance to Chapter 15, where the seven habits of happiness await.

13

INTELLIGENT AND LAZY

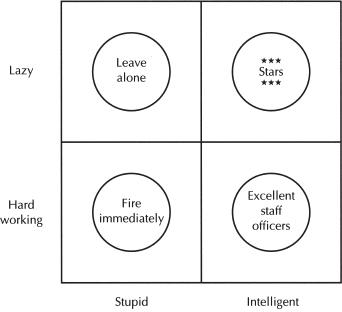

There are only four types of officer. First, there are the lazy, stupid ones. Leave them alone, they do no harm…Second, there are the hard-working intelligent ones. They make excellent staff officers, ensuring that every detail is properly considered. Third, there are the hard-working, stupid ones. These people are a menace and must be fired at once. They create irrelevant work for everybody. Finally, there are the intelligent lazy ones. They are suited for the highest office.

G

ENERAL

V

ON

M

ANSTEIN

on the German Officer Corps

This is a chapter for the truly ambitious. If you do not suffer from the insecurity that fuels the desire to be rich or famous, move on to Chapter 15. But if you want to win the rat race, here is some advice that may surprise you.

General Von Manstein captures the essence of this chapter, which is the 80/20 Principle’s guidance on how to have a successful career. If the general had been a management consultant, he would have made a fortune out of the matrix shown in Figure 37.

Figure 37 The Von Manstein matrix

This advice is what to do about other people. But what about yourself? It might be thought that intelligence and propensity to work are fixed properties, in which case the Von Manstein matrix, although interesting, is useless. But the position advanced in this chapter is slightly different. Even if you are hard working, you can learn to become lazy. And even if you or other people think you are stupid, you are intelligent at something. The key to becoming a star is to simulate, manufacture, and deploy lazy intelligence. As we will see, lazy intelligence can be worked at. The key to earning more and working less is to pick the right thing to do and to do only those things that add the highest value.

First, however, it is instructive to see how the 80/20 Principle distributes rewards to those who work. Rewards are both unbalanced and unfair. We can either complain about this or align ourselves to take advantage of the Von Manstein matrix.

IMBALANCE IS RAMPANT IN PROFESSIONAL SUCCESS AND RETURNS

The 80/20 Principle is nowhere more evident today than in the very high and increasing returns enjoyed by very small numbers of élite professionals.

We live in a world where the returns for top talent, in all spheres of life, have never been higher. A small percentage of professionals obtain a disproportionate amount of recognition and fame and usually also a high percentage of the spoils available.

Take any sphere of contemporary human endeavor, in any country or globally. Whether the sphere be athletics, baseball, basketball, football, golf, rugby, tennis, or any other popular sport; or architecture, sculpture, painting, or any other visual art; or music of any category; the movies or the theater; novels, cookery books, or autobiography; or even hosting TV chat shows, reading the news, politics, or any other well-defined area, there will be a small number of preeminent professionals whose names spring to mind.

Considering how many people there are in each country, it is a remarkably small number of names, and usually a small percentage—typically well under 5 percent—of the professionals active in the relevant sphere. The fraction of any profession who are recognized “names” is very small, but they hog the limelight. They are always in demand and always in the news. They are the human equivalent of consumer goods brands, obtaining instant recognition as known quantities.

The same concentration operates with regard to popularity and financial rewards. More than 80 percent of novels sold are from fewer than 20 percent of novel titles in print. The same is true of any other category of publishing: of pop CDs and concerts, of movies, even of books about business. The same applies to actors, TV celebrities, or any branch of sports. Eighty percent of prize money in golf goes to fewer than 20 percent of professional golfers; the equivalent is true in tennis; and in horseracing, more than 80 percent of winnings go to fewer than 20 percent of owners, jockeys, and trainers.

We live in an increasingly marketized world. The top names can command enormous fees—but those who are not quite as good or well known make relatively little.

There is a big difference between being at the top, and well known to all, and being almost at the top, and well known only to a few enthusiasts. The best-known baseball, basketball, or football stars can make millions; those just below the top rank, only a comfortable living.

Why do the winners take all?

The distribution of incomes for superstars is even more unbalanced than for the population as a whole and provides excellent illustrations of the 80/20 Principle (or in most cases, 90/10 or 95/5). Various writers have sought economic or sociological explanations of the superreturns to superstars.

1

The most persuasive explanation is that two conditions facilitate superstar returns. One is that it is possible for the superstar to be accessible to many people at once. Modern communications enable this to happen. The incremental cost of “distributing” Janet Jackson, J. K. Rowling, Steven Spielberg, Oprah Winfrey, Paris Hilton, Roger Federer, Mariah Carey, or David Beckham to additional customers can be almost nothing, since the additional cost of broadcasting, making a CD, or printing a book is a very small part of the total cost structure.

The additional cost of making these superstars available is certainly no more than for a second-rate substitute, except in so far as the superstars themselves take a higher fee. Although the fee may be many millions or tens of millions, the incremental cost per consumer is very low indeed, often a matter of cents or fractions of a cent.

The second condition for superstar returns is that mediocrity must not be a substitute for talent. It must be important to obtain the best. If one house cleaner is half as quick as another, the market will clear by paying her half as much. But who wants someone who is half as good as Tiger Woods, Celine Dion, or Andrea Bocelli? In this case, the non-superstar, even working for nothing, would have vastly inferior economics to the superstar. The non-superstar would attract a smaller audience and, for a tiny decrease in the total cost, bring in very much lower revenues.

Winner takes all is a modern phenomenon

What is intriguing is that this disparity between top returns and the rest has not always existed. The best basketball or football champions of the 1940s and 1950s, for example, did not make much money. It used to be possible to find a prominent politician who died fairly poor. And the further back we go, the less true it was that the winner took all.

For instance, William Shakespeare was absolutely preeminent in terms of talent among his contemporaries. So was Leonardo da Vinci. By rights or, rather, by today’s standards, they should have been able to exploit their brilliance, creativity, and fame to become the richest men of their times. Instead, they made do with the sort of income that is enjoyed today by millions of moderately talented professionals.

The imbalance of financial rewards for talent is becoming more and more pronounced over time. Today, income is more closely linked to merit and marketability, so that the 80/20 connection, because it can be clearly demonstrated in money terms, becomes easily apparent. Our society is clearly more meritocratic than that of a century, or even a generation, ago. This is particularly so in Europe generally and Great Britain in particular.

If top footballers like Bobby Moore had made fortunes in the 1940s or 1950s, it would have provoked fury among the British Establishment; it would have been unseemly. When the leader writers of the 1960s discovered that the Beatles were millionaires, it caused astonishment. Today the fact that Madonna is worth at least $325 million, J. K. Rowling $1 billion, and Oprah Winfrey $1.5 billion causes no surprise or outrage.

2

Nowadays we have less respect for rank and more for markets.

The other new element is, as mentioned above, the technological revolution in broadcasting, telecommunications, and consumer products like the CD and CD-Rom. The key consideration now is to maximize revenue, which superstars can do. The extra cost of hiring them may be a huge amount of money for an individual, but the cost per consumer is trivial.

ACHIEVEMENT HAS ALWAYS OBEYED THE 80/20 PRINCIPLE

If we set money aside and deal in the more enduring and important matters (at least for everyone except the superstars themselves), we can see that the concentration of achievement and fame in very few people, whatever the profession, has always been true. Constraints that seem odd to our eyes—such as class or the absence of telecommunications—stopped Shakespeare and Leonardo da Vinci becoming millionaires. But lack of wealth did not diminish their achievements or the fact that a huge proportion of impact came from a tiny proportion of creators.

80/20 RETURNS ALSO APPLY TO NONMEDIA PROFESSIONALS

Although it is most noticeable and exaggerated with respect to media superstars, it is significant that 80/20 returns are not confined to the world of entertainment. In fact, celebrities comprise only 3 percent of multimillionaires. The majority of the 7 million or so Americans in the $1–10 million bracket are professionals of one sort or another: executives, Wall Street types, top lawyers and doctors, and the like. Moving up to the 1.4 million Americans who own $10–100 million, there are twice as many entrepreneurs as in the “poorer millionaire” category. When we reach the much smaller number (some thousands) of Americans worth $100 million–$1 billion, entrepreneurs and money managers predominate. The same is true in the billionaire category, where

Forbes

magazine counted 946 in 2007, including no fewer than 178 new entries and seventeen re-entries.

3