Ancient Iraq (36 page)

Sargon II

The short reign of Tiglathpileser's son, Shalmaneser V (726-722

B.C.

), is obscure. All we know for certain is that Hoshea, the puppet King of Israel, revolted and that Shalmaneser besieged Samaria for three years; but whether it was he or the next King of Assyria who captured the city is still a debated question.

25

Equally obscure are the circumstances which brought his successor to the throne, and no one can say whether he was a usurper or another of Tiglathpileser's sons. In any case, the name he took was in itself a promise of glory, for he called himself

Sharru-kin

(Sargon), like one of the earliest kings of Assur and like the illustrious founder of the Dynasty of Akkad.

26

Shortly before Sargon was enthroned two events of capital importance, which were to influence Assyrian strategy and diplomacy for a hundred years, took place in the Near East: the interference of Egypt in Palestine and of Elam in Babylonia. Both were the consequences of Tiglathpileser's victory, since his

advance on the Iranian plateau had cut across the only trade routes left open to Elam, while his conquest of Phoenicia had wrested from Egypt one of her main clients. Elamites and Egyptians therefore joined the Urartians as Assyria's avowed enemies, but since neither of them were yet capable of attacking a nation at the peak of its power, they had recourse to slower but safer methods: they fostered revolts among the vassals of Assyria, and whenever the Aramaean sheikhs of southern Iraq or the princelings of Palestine threatened by the invincible Assyrian army begged for help, they lent them all the support they could in men and weapons. The political history of Sargon's reign is in fact nothing but the beginning of a long struggle against such rebellions.

Trouble, however, began at home, and for a year Sargon had his hands tied by domestic disorders which ended after he had freed the citizens of Assur from ‘the call to arms of the land and the summons of the tax-collector’ imposed upon them by Shalmaneser V. Only then could he deal with the critical situation which had arisen in Babylonia and Syria during the change of reign. In Babylonia – now the second jewel of the Assyrian crown – a Chaldean ruler from Bit-Iakin, on the shores of the Persian Gulf, Marduk-apal-iddina

*

(Merodach-Baladan of the Old Testament), had ascended the throne in the same year as Sargon and was actively supported by Humbanigash, King of Elam. In 720

B.C.

Sargon marched against him and met his enemies at Dêr (Badrah), between the Tigris and the Zagros. His inscriptions claim complete victory, but the more impartial ‘Babylonian Chronicle’ clearly states that the Assyrians were defeated by the Elamites alone, while Merodach-Baladan in another text proudly declares that ‘he smote to overthrow the widespread hosts of Subartu (Assyria) and smashed their weapons’.

27

Amusing detail: Merodach-Baladan's inscription was found at Nimrud, where Sargon had taken it from Uruk after 710

B.C.

, replacing it in that city with a clay cylinder bearing

his own radically different version of the event. This shows that political propaganda and ‘disinformation’ are not the privilege of our epoch. There can be no doubt, however, that the Assyrians met with a check, for we know that Marduk-apal-iddina reigned over Babylonia for eleven years (721 – 710

B.C.

), behaving not as a barbarian chieftain but as a great Mesopotamian monarch and leaving traces of his building activities in various cities.

Not less dangerous for Assyria was the coalition of revolted Syrian provinces headed by Ilu-bi'di, King of Hama, and the rebellion of Hanuna, King of Gaza, assisted by an Egyptian army. But here Sargon had better luck. Ilu-bi'di who, with his allies, was defeated at Qarqar, was captured and flayed, whilst Hanuna was spared. As for the Egyptian general Sib'e, he ‘fled alone and disappeared like a shepherd whose flock has been stolen’ (720

B.C

.).

28

Eight years later the Egyptians fomented another revolt in Palestine. This time the leader was Iamani, King of Ashdod, followed by Judah, Edom and Moab and supported by ‘Pi'ru of Musru’, i.e. Pharaoh of Egypt (probably Bocchoris). Again Sargon was victorious: Iamani fled to Egypt, but he was soon extradited by the Nubian king Sabakho who then held sway over the Nile valley:

He threw him in fetters, shackles and iron bands, and they brought him to Assyria, a long journey.

29

The friendly attitude of the new ruler of Egypt towards Assyria accounts for the calm which reigned in Palestine during the rest of Sargon's reign.

We do not know for sure whether the Elamites had a hand in the dissensions which broke out among the ruling families of the central Zagros and gave Sargon in 713

B.C.

the opportunity of conquering various principalities and towns in the regions of Kermanshah and Hamadan and to receive tribute from the Medes, but there can be no doubt as to who fomented trouble among the Mannaeans, the Zikirtu and other tribes of Azerbai

jan, for Urartu remained in the north the main enemy of Assyria. A glance at Sargon's correspondence shows at once the care with which the Assyrian officials posted in those mountainous districts ‘kept the watch of the king’ and informed him of every move made by the Urartian monarch or his generals, of every change in the political loyalties of the surrounding peoples.

30

Yet, despite repeated interventions by Sargon, Rusas I of Urartu managed, between 719

B.C.

and 715

B.C.

, to replace the Mannaean rulers friendly to Assyria by his own creatures. In 714

B.C

. the Assyrians launched a large-scale counter-offensive. The great campaign of Sargon's eighth year is recorded in his Annals, but a more detailed account of it has reached us in the form of a letter curiously addressed by the king to ‘Ashur, father of the gods, the gods and goddesses of Destiny, the city and its inhabitants and the palace in its midst’ – most certainly a document written to be read in public at the end of the annual campaign, with the view of creating a strong impression.

31

The march through the mountains of Kurdistan was exceptionally difficult, owing to the geography of the region no less than the resistance of the enemy, and our text abounds in poetic passages like this:

‘Mount Simirria, a great peak which stands like the blade of a lance, lifting its head above the mountains, abode of Bêlit-ilâni; whose summit on high upholds the heavens and whose roots below reach the centre of the netherworld; which, like the spine of a fish, has no passage from side to side and whose ascent from back to front is difficult; on whose flanks gorges and precipices yawn, whose sight inspires fear… with the wide understanding and the inner spirit endowed to me by Ea and Bêlit-ilâni, who opened my legs to overthrow the enemy countries, with picks of bronze I armed my pioneers. The crags of high mountains they caused to fly in splinters; they improved the passage. I took the head of my troops. The chariots, the cavalry, the fighters who went beside me, I made fly over this mountain like valiant eagles…’

32

Sargon crossed rivers and mountains, fought his way around Lake Urmiah and perhaps Lake Van and finally conquered

Urartu's most sacred city Musasir (south of Lake Van), taking away the national god Haldia. Urartu was not destroyed, but it had suffered a crushing defeat. At the news of the fall of Musasir, Ursâ (Rusas) was overwhelmed with shame: ‘With his own dagger he stabbed himself through the heart like a pig and ended his life.’

But the Urartians had already had time to rouse anti-Assyrian feelings in other countries. In 717

B.C

. the still independent ruler of Karkemish plotted against Sargon and saw his kingdom invaded and turned into an Assyrian province. During the next five years the same fate befell Quê (Cilicia), Gurgum, Milid, Kummuhu and part of Tabal, in other words all the Neo-Hittite kingdoms of the Taurus. Behind these plots and ‘revolts’ were not only ‘the man of Urartu’, but also Mitâ of Mushki (that is, Midas, King of Phrygia), whom Rusas had managed to attract into his sphere of influence.

At the beginning of 710

B.C.

Sargon was everywhere victorious. The whole of Syria-Palestine (with the notable exception of Judah) and most of the Zagros range were firmly in Assyrian hands; the Medes were regarded as vassals; Urartu was dressing its wounds; the Egyptians were friendly, the Elamites and Phrygians hostile but peaceful. Yet Babylon under Merodach-Baladan remained as a thorn in the side of Assyria, and in that same year Sargon attacked it for the second time in his reign. The Chaldaean had enlisted the help of all the tribes dwelling in the ancient country of Sumer, and for two years he offered strong resistance to the Assyrian Army. Finally, encircled in Dûr-Iakîn (Tell Lahm) and wounded in the hand, he ‘slipped in through the gate of his city like mice through holes’ and took refuge in Elam. Sargon entered Babylon and, like Tiglathpileser III, ‘took the hand of Bêl. The repercussions of his victory were enormous: Midas the Phrygian offered him his friendship; Upêri, King of Dilmun (Bahrain), ‘heard of the might of Assur and sent him gifts’. Seven kings of Iatnana (Cyprus), ‘whose distant abodes are situated a seven days’ journey in the sea of the setting sun’, sent presents and swore allegiance to the

mighty monarch whose stele has actually been found at Larnaka. The repeated efforts made by its enemies to undermine the Assyrian empire had been of no avail; at the end of the reign it was larger and apparently stronger than ever.

As a war-chief Sargon liked to live in Kalhu (Nimrud), the military capital of the empire, where he occupied, restored and modified Ashurnasirpal's palace. But moved by incommensurable pride, he soon decided to have his own palace in his own city. In 717

B.C.

were laid the foundations of ‘Sargon's fortress’,

Dûr-Sharrukîn

, a hitherto virgin site twenty-four kilometres to the north-east of Nineveh, near the modern village of Khorsabad.

33

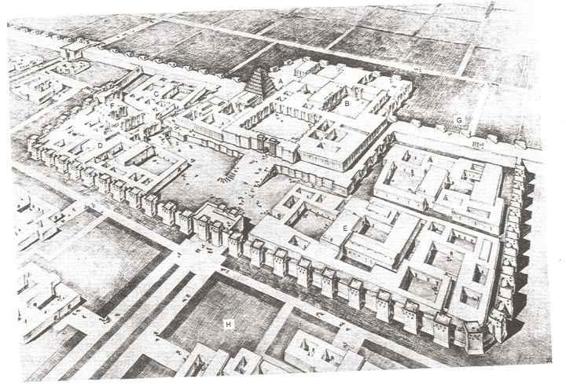

The town was square in plan, each side measuring more than one and a half kilometres, and its wall was pierced by seven fortified gates. In its northern part an inner wall enclosed the citadel, which contained the royal palace, a temple dedicated to Nabû and the sumptuous houses of high-ranking officials, such as Sin-ah-usur, the vizier and king's brother. The palace itself stood on a sixteen-metre-high platform overriding the city wall and comprised more than two hundred rooms and thirty courtyards. Part of it, erroneously called ‘harem’ by the early excavators, was later found to be made of six sanctuaries, and near by rose a ziqqurat of which the seven storeys were painted with different colours and connected by a spiral ramp. A beautiful viaduct of stone linked the palace with the temple of Nabû, for in Assyria the religious and public functions of the king were closely interwoven. As expected, the royal abode was lavishly decorated. Its gates and main doors – as, indeed, the gates of the town and of the citadel – were guarded by colossal bull-men; blue glazed bricks showing divine symbols were used in the sanctuaries, and in most rooms the walls were adorned with frescoes and lined with sculptured and inscribed orthostats, a mile and a half long. Thousands of prisoners of war and hundreds of artists and craftsmen must have worked at Dûr-Sharrukin, since the whole city was built in ten years. In one of his so-called ‘Display Inscriptions’ Sargon says:

The citadel of Dûr-Sharrukîn (Khorsabad). A, ziqqurat; B, Sargon's palace; C, C-E, residences of high officials; F, Nabû's temple; G, outer wall of the town; H, lower town.

From G. Loud and Ch. B. Altman

, Khorsabad,

II, 1938

.

‘For me, Sargon, who dwells in this palace, may he (Ashur) decree as my destiny long life, health of body, joy of heart, brightness of soul.’

34

But the god hearkened not to his prayer. One year after Dûr-Sharrukin was officially inaugurated Sargon ‘went against Tabal and was killed in the war’ (705

B.C

.). His successors preferred Nineveh to the Mesopotamian Brazilia, but Khorsabad remained inhabited by governors and their retinue: until the final collapse of Assyria.

35

CHAPTER 20

Sargon's descendants – the Sargonids, as they are sometimes called – governed Assyria in unbroken succession for almost a century (704 – 609

B.C

.), bringing the Assyrian empire to its farthest limits and the Assyrian civilization to its zenith. Yet the wars of Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, which through the inflated language of the royal inscriptions look like glorious wars of conquest, were, at their best, nothing but successful counter-attacks. At the end of Sargon's reign the Assyrians ruled, directly or indirectly, over the entire Fertile Crescent and over parts of Iran and Asia Minor. They had a window on the Mediterranean and a window on the Gulf; they controlled the entire course of the Tigris and the Euphrates as well as the great trade routes crossing the Syrian desert, the Taurus and the Zagros. Supplied with all kinds of goods and commodities by their subjects, vassals and allies, they lived in prosperity and could have lived in peace, had it not been for the increasingly frequent revolts provoked by their oppressive policy and encouraged – at least in Palestine and Babylonia – by Egypt and Elam. The conquest of Egypt by Esarhaddon and the destruction of Elam at the hands of Ashurbanipal were therefore neither long-range razzias in the traditional style nor the fruits of a planned strategy: they were defensive measures taken by these monarchs to put an end to an unbearable situation; they represent the final outcome of long and bitter conflicts more imposed upon Assyria by her enemies than desired by her. In this endless struggle the Assyrians used up their strength, ruined their own possessions and failed to pay sufficient attention to the capital event which was taking place during that time behind the screen of the Zagros: the formation of a powerful Median kingdom, the future instrument of

their downfall. About 640

B.C

. when total victory seemed at last achieved, when Ashurbanipal rose in triumph over all the foes of Assyria, it suddenly became apparent that the colossus had feet of clay.