Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (733 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

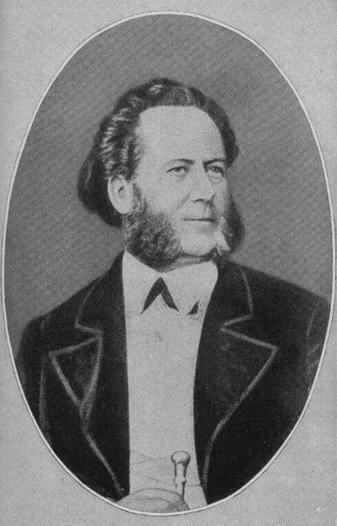

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

While he was writing

The Vikings at Helgeland

, and courting Susannah Thoresen, Ibsen received what seemed a timely invitation to settle in Christiania as director of the Norwegian Theatre; he returned, thereupon, to the capital in the summer of 1857, after an absence of six years. Now began another period of six years more, these the most painful in Ibsen’s life, when, as Halvorsen has said, he had to fight not merely for the existence of himself and his family, but for the very existence of Norwegian poetry and the Norwegian stage. This struggle was an excessively distressing one. He had left Bergen crippled with debts, and his marriage (June 26, 1856) weighed him down with further responsibilities. The Norwegian Theatre at Christiania was, a secondary house, ill-supported by its patrons, often tottering at the brink of bankruptcy, and so primitive was the situation of literature in the country that to attempt to live by poetry and drama was to court starvation. His slender salary was seldom paid, and never in full. The only published volume of Ibsen’s which had (up to 1863) sold at all was

The Warriors

, by which he had made in all 227 specie dollars (or about £25).

The Christiania he had come to, however, was not that which he had left. In many directions it had developed rapidly. From an intellectual point of view, the labors of the nationalists had made themselves felt; the folk-lore of Landstad, Moe and Asbjörnsen had impressed young imaginations. In some of its forms the development was unpleasing and discouraging to Ibsen; the success of the blank-verse tragedies of Andreas Munch (

Salomon de Caus

, 1855;

Lord William Russell

, 1857) was, for instance, an irritating step in the wrong direction. The new- born school of prose fiction, with Björnson as its head (

Synnöve Solbakken

, 1857;

Arne

, 1858), with Camilla Collett’s

Prefect’s Daughters

, 1855, as its herald; with Östgaard’s sketches of peasant life and humors in the mountains (1852) — all this was a direct menace to the popularity of the national stage, offering an easy and alluring alternative for home-loving citizens. Was it certain that the classic Danish, which alone Ibsen cared to write, would continue to be the language of the cultivated classes in Norway? Here was Ivar Aasen (in 1853) showing that the irritating landsmaal could be used for prose and verse.

Wherever he turned Ibsen saw increased vitality, but in shapes that were either useless or antagonistic to himself, and all that was harsh and saturnine in his nature awakened. We see Ibsen, at this moment of his life, like Shakespeare in his darkest hour, “in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,” unappreciated and ready to doubt the reality of his own genius; and murmuring to himself: —

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possess’d,

Desiring this man’s art, and that man’s scope.

With what I most enjoy contented least.

How little his greatness was perceived in the Christiania literary coteries may be gathered from the little fact that the species of official anthology of

Modern Norwegian Poets

, published in 1859, though it netted the shallows of national song very closely, contained not a line by the author of the lovely lyrics in

The Feast at Solhoug

. It was at this low and miserable moment that Ibsen’s talent suddenly took wings; he conceived, in the summer of 1858, what finally became, five years later, his first acknowledged masterpiece, and perhaps the most finished of all his writings, the sculptural tragedy of

The Pretenders

.

The Pretenders

(

Kongsemnerne

, properly stuff from which Kings can be made) is the earliest of the plays of Ibsen in which the psychological interest is predominant, and in which there is no attempt to disguise the fact. Nothing that has since been written about this drama, the very perfection of which is baffling to criticism, has improved upon the impression which Georg Brandes received from it when he first read it forty years ago. The passage is classic, and deserves to be cited, if only as perhaps the very earliest instance in which the genius of Ibsen was rewarded by the analysis of a great critic. Brandes wrote (in 1867): —

What is it that The Pretenders treats of? Looked at simply, it is an old story. We all know the tale of Aladdin and Nureddin, the simple legend in the Arabian Nights, and our great poet’s [Oehlenschläger’s] incomparable poem. In

The Pretenders

two figures again stand opposed to one another as the superior and the inferior being, an Aladdin and a Nureddin nature. It is towards this contrast that Ibsen has hitherto unconsciously directed his endeavors, just as Nature feels her way in her blind preliminary attempts to form her types. Håkon and Skule are pretenders to the same throne, scions of royalty out of whom a king may be made. But the first is the incarnation of fortune, victory, right and confidence; the second — the principal figure in the play, masterly in its truth and originality — is the brooder, a prey to inward struggle and endless distrust, brave and ambitious, with perhaps every qualification and claim to be king, but lacking the inexpressible, impalpable somewhat that would give a value to all the rest — the wonderful Lamp. “I am a king’s arm,” he says, “mayhap a king’s brain as well; but Håkon is the whole king.” “You have wisdom and courage, and all noble gifts of the mind,” says Håkon to him; “you are born to stand nearest a king, but not to be a king yourself.”

To a poet the achievements of his greatest contemporaries in their common art have all the importance of high deeds in statesmanship and war. It is, therefore, by no means extravagant to see in the noble emulation of the two dukes in

The Pretenders

some reflection of Ibsen’s attitude to the youthful and brilliant Björnson. The luminous self-reliance, the ardor and confidence and good fortune of Björnson- Håkon could not but offer a violent contrast with the gloom and hesitation, the sick revulsions of hope and final lack of conviction, of Ibsen-Skule. It was Björnson’s “belt of strength,” as it was Håkon’s, that he had utter belief in himself, and with this his rival could not yet girdle himself. “The luckiest man is the greatest man,” says Bishop Nicholas in the play, and Björnson seemed in these melancholy years as lucky as Ibsen was unlucky. But the Bishop’s views were not wide enough, and the end was not yet.

CHAPTER IV. THE SATIRES (1857-67)

Temperament and environment combined at the period we have now reached to turn Ibsen into a satirist. It was during his time of

Sturm und Drang

, from 1857 to 1864, that the harshest elements in his nature were awakened, and that he became one who loved to lash the follies of his age. With the advent of prosperity and recognition this phase melted away, leaving Ibsen without illusions and without much pity, but no longer the scourge of his fellow-citizens. Although

The Pretenders

, a work of dignified and polished aloofness, was not completed until 1863, it really belongs to the earlier and more experimental section of Ibsen’s works, and is so completely the outcome and the apex of his national studies that it has seemed best to consider it with

The Vikings at Helgeland

, in spite of its immense advance upon that drama. But we must now go back a year, and take up an entirely new section which overlaps the old, namely, that of Ibsen’s satires in dramatic rhyme.

With regard to the adoption of that form of poetic art, a great difference existed between Norwegian and English taste, and this must be borne in mind. Almost exactly at the date when Ibsen was inditing the sharp couplets of his

Love’s Comedy

, Tennyson, in

Sea Dreams

, was giving voice to the English abandonment of satire — which had been rampant in the generation of Byron — in the famous words: —

I loathe it: he had never kindly heart,

Nor ever cared to better his own kind,

Who first wrote satire, with no pity in it.

What England repudiated, Norway comprehended, and in certain hands enjoyed. Polemical literature, if seldom of a high class, was abundant and was much appreciated. The masterpiece of modern Norwegian poetry was, still, the satiric cycle of Welhaven. In ordinary controversy, the tone was more scathing, the bludgeon was whirled more violently, than English taste at that period could endure. Those whom Ibsen designed to crush had not minced their own words. The press was violence itself, and was not tempered with justice; when the poet looked round he saw “afflicted virtue insolently stabbed with all manner of reproaches,” as Dryden said.

Yet it was not an age of gross and open vices; manners were not flagitious, they were merely of a nauseous insipidity. Ibsen, flown with anger as with wine, could find no outrageous offences to lash, and all he could invite the age to do was to laugh at certain conventions and to reconsider some prejudicated opinions. He had to be pungent, not openly ferocious; he had to be sarcastic and to treat the current code of morals as a jest. He found the society around him excessively distasteful to him, but there were no crying evils of a political or ethical kind to be stigmatized. What was open to him was what an old writer of our own defined as “a sharp, well-mannered way of laughing a folly out of countenance.”

Unfortunately, the people laughed at will never consent to think the way well mannered, and Ibsen was bitterly blamed for “want of taste,” that vaguest and most insidious of accusations. We are told that he began his enterprise in prose [Note: “

Svanhild

: a Comedy in three acts and in prose:

Love’s Comedy

, therefore, anew, and he wrote it as a pamphlet in rhyme. It is not certain that he had any very definite idea of the line which his attack should take. He was very poor, very sore, very uncomfortable, and he was easily convinced that the times were out of joint. Then he observed that if there was anything that the Norwegian upper classes prided themselves upon it was their conduct of betrothal and marriage. Plato had said that the familiarity of young persons before marriage prevented enmity and disappointment in later years, that it was useful to know the peculiarities of temperament beforehand, and so, being accustomed to them, to discount them. But Ibsen was not of this opinion, or rather, perhaps, he did not choose to be. The extremely slow and public method of betrothal in the North gave him his first opportunity.

It is with a song, in the original one of the most delicious of his lyrics, that he opens the campaign. To a miscellaneous party of Philistines circled around the tea table, “all sober and all — —” the rebellious hero sings: —

In the sunny orchard-closes,

While the warblers sing and swing,

Care not whether blustering Autumn

Break the promises of Spring;

Rose and white the apple-blossom

Hides you from the sultry sky;

Let it flutter, blown and scattered,

On the meadow by and by.

In the sexual struggle, that is to say, the lovers should not pause to consider the worldly advantages of their match, but should fly in secret to each other’s arms. By the law of battle, the female should be snatched to the conqueror’s saddle-bow, and ridden away with into the night, not subjected to the jokes and the good advice and the impertinent congratulations of the clan. Young Lochinvar does not wait to ask the counsel of the bride’s cousins, nor to run the gantlet of her aunts; he fords the Esk river with her, where ford there is none. Ibsen is in favor of the

mariage de convenance

, which suppresses, without favor, the absurdity of love-matches. Above all, anything is better than the publicity, the meddling and long-drawn exposure of betrothal, which kills the fine delicacy of love, as birds are apt to break their own eggs if intruding hands have touched them.

This is the central point in

Love’s Comedy

, but there is much beside this in its reckless satire on the “sanctities” of domestic life. The burden of monogamy is frivolously dealt with, and the impertinent poet touches with levity upon the question of the duration of marriage:

With my living, with my singing,

I will tear the hedges down!

Sweep the grass and heap the blossom!

Let it shrivel, pale and blown!

Throw the wicket wide! Sheep, cattle,

Let them browse among the best

!

I

broke off the flowers; what matter

Who may graze among the rest!

Love’s Comedy

is perhaps the most diverting of Ibsen’s works; it is certainly the most impertinent. If there was one class in Norwegian society which was held to be above criticism it was the clerical. A prominent character in Ibsen’s comedy is the Rev. Mr. Strawman, a gross, unctuous and uxorious priest, blameless and dull, upon whose inert body the arrows of satire converge. This was never forgotten and long was unforgiven. As late as 1866 the Storthing refused a grant to Ibsen definitely on the ground of the scandal caused by his sarcastic portrait of Pastor Strawman. But the gentler sex, to which every poet looks for an audience, was not less deeply outraged by the want of indulgence which he had shown for all forms of amorous sentiment, although Ibsen had really, through his satire on the methods of betrothal, risen to something like a philosophical examination of the essence of love itself.

To Brandes, who reproached him for not recording the history of ideal engagements, and who remarked, “You know, there are sound potatoes and rotten potatoes in this world,” Ibsen cynically replied, “I am afraid none of the sound ones have come under my notice”; and when Guldstad proves to the beautiful Svanhild the paramount importance of creature comforts, the last word of distrust in the sustaining power of love had been said. The popular impression of Ibsen as an “immoral” writer seems to be primarily founded on the paradox and fireworks of

Love’s Comedy

.

Much might be forgiven to a man so wretched as Ibsen was in 1862, and more to a poet so lively, brilliant and audacious in spite of his misfortunes. These now gathered over his head and threatened to submerge him altogether. He was perhaps momentarily saved by the publication of

Terje Vigen

, which enjoyed a solid popularity. This is the principal and, indeed, almost the only instance in Ibsen’s works of what the Northern critics call “epic,” but what we less ambitiously know as the tale in verse.

Terje Figen

will never be translated successfully into English, for it is written, with brilliant lightness and skill, in an adaptation of the Norwegian ballad-measure which it is impossible to reproduce with felicity in our language.

Among Ibsen’s writings

Terje Vigen

is unique as a piece of pure sentimentality carried right rough without one divagation into irony or pungency. It is the story of a much-injured and revengeful Norse pilot, who, having the chance to drown his old enemies, Milord and Milady, saves them at the mute appeal of their blue-eyed English baby.

Terje Vigen

is a masterpiece of what we may define as the “dash-away-a-manly- tear” class of narrative. It is extremely well written and picturesque, but the wonder is that, of all people in the world, Ibsen should have written it.

His short lyric poems of this period betray much more clearly the real temper of the man. They are filled full and brimming over with longing and impatience, with painful passion and with hope deferred. It is in the strident lyrics Ibsen wrote between 1857 and 1863 that we can best read the record of his mind, and share its exasperations, and wonder at its elasticity. The series of sonnets

In a Picture Gallery

is a strangely violent confession of distrust in his own genius; the

Epistle to H. O. Blom

a candid admission of his more than distrust in the talent and honesty of others. It was the peculiarity and danger of Ibsen’s position that he represented no one but himself. For instance, the liberty of many of the expressions in

Love’s Comedy

led those who were beginning a movement in favor of the emancipation of women to believe that Ibsen was in sympathy with them, but he was not. All through his life, although his luminous penetration into character led him to be scrupulously fair in his analysis of female character, he was never a genuine supporter of the extension of public responsibility to the sex. A little later (in 1869), when John Stuart Mill’s

Subjection of Women

produced a sensation in Scandinavia, and met with many enthusiastic supporters, Ibsen coldly reserved his opinion. He was always an observer, always a clinical analyst at the bedside of society, never a prophet, never a propagandist.

His troubles gathered upon him. Neither theatre consented to act

Love’s Comedy

, and it would not even have been printed but for the zeal of the young novelist Jonas Lie, who, to his great honor, bought for about £35 the right to publish it as a supplement to a newspaper that he was editing. Then the storm broke out; the press was unanimously adverse, and in private circles abuse amounted almost to a social taboo. In 1862 the second theatre became bankrupt, and Ibsen was thrown on the world, the most unpopular man of his day, and crippled with debts. It is true that he was engaged at the Christiania Theatre at a nominal salary of about a pound a week, but he could not live on that. In August, 1860, he had made a pathetic appeal to the Government for a

digter-gage

, a payment to a poet, such as is freely given to talent in the Northern countries. Sums were voted to Björnson and Vinje, but to Ibsen not a penny. By some influence, however, for he was not without friends, he was granted in March,

Brand

and

Peer Gynt

.

All through 1863 his condition was critical. He determined that his only hope was to exile himself definitely from Norway, which had become too hot to hold him. Various private friends generously helped him over this dreadful time of adversity, earning a gratitude which, if it was not expansive, was lifelong. Very grudging recognition of his gifts was at length made by the Government in the shape of another trifling travelling grant (March, 1863), again a handsome sum being awarded to Björnson, his popular rival. In May Ibsen applied, in despair, to the King himself, who conferred upon him a small pension of £90 a year, which for the immediate future stood between this great poet and starvation. The news of it was received in Christiania by the press in terms of despicable insult.

But in June of this

année terrible

Ibsen had a flash of happiness. He was invited down to Bergen to the fifth great “Festival of Song,” a national occurrence, and he and his poems met with a warm reception. Moreover, he found his brilliant antagonist, Björnson, at Bergen on a like errand, and renewed an old friendship with this warm-hearted and powerful man of genius, destined to play through life the part of Håkon to Ibsen’s Skule. They spent much of the subsequent winter together. As Halvdan Koht has excellently said: “Their intercourse brought them closer to each other than they had ever been before. They felt that they were inspired by the same ideas and the same hopes, and they suffered the same bitter disappointments. With anguish they watched the Danish brother-nation’s desperate struggle against the superior power of Germany, and save a province with a population of Scandinavian race and speech taken from Denmark and incorporated in a foreign kingdom, whilst the Norwegian and Swedish kinsmen, in spite of solemn promises, refrained from yielding any assistance.” An attack on Holstein (December 22, 1863) had introduced the Second Danish War, to which a disastrous and humiliating termination was brought in the following August.