Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child (13 page)

Read Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child Online

Authors: JOHN GOTTMAN

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Parenting, #General, #Psychology, #Developmental, #Child, #Child Rearing, #Child Development

39

. In life, it is best not to dwell too long with negative emotions; just accentuate the positive.

T F DK

40

. To get over a negative emotion, just get on with life’s routines.

T F DK

S

CORING

People who are aware of anger and sadness speak about these emotions in a differentiated manner. They can easily detect such emotions in themselves and in others. They experience a variety of nuances with these emotions, and they allow these feelings to be a part of their lives. Such people are likely to see and respond to smaller and less intense expressions of anger or sadness in their children than people lower in emotional awareness.

Can you be high in awareness for one emotion and low for another? This is quite possible. Awareness is not one-dimensional and it can change over time.

ANGER. To compute your score for anger, add up the number

of times you said “true” for the items in List No. 1 below, and then subtract the number of times you said “true” for the items in List No. 2 below. The higher your score, the greater your awareness.

List No. 1

1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 44.

List No. 2

2, 6, 9, 13, 14, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43.

If you responded “don’t know” more than ten times, you may want to work at becoming more aware of anger in yourself and others.

SADNESS. To compute your score for sadness, add up the number of times you said “true” for the items in List No. 1 below, and then subtract the number of times you said “true” for the items in List No. 2 below. The higher your score, the greater your awareness.

List No. 1

4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, 21, 24, 31, 35.

List No. 2

1, 2, 3, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40.

If you responded “don’t know” more than ten times, you may want to work at becoming more aware of sadness in yourself and others.

TIPS FOR EMOTIONAL SELF-AWARENESS

After taking this test, you may find that you want to develop a deeper awareness of your own emotional life. Common ways to tap into your feelings include meditation, prayer, journal writing, and forms of artistic expression, such as playing a musical instrument or drawing. Keep in mind that building greater emotional awareness requires a bit of solitude, something that’s often in short supply for today’s busy parents. If you remind yourself, however, that time

spent alone can help you to become a better parent, it doesn’t seem so indulgent. Couples may want to take turns getting out alone for early morning walks or taking off for a weekend retreat from time to time. Single parents may want to trade child care with one another for the same purpose.

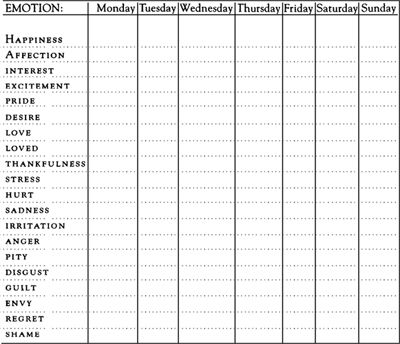

Keeping an “emotion log” is also an excellent way to become more aware of your feelings moment by moment. The chart on the next page is an example of a weekly checklist for keeping track of a variety of feelings as they come up. In addition to the checklist, you may want to keep a brief emotion diary for writing down thoughts about feelings as you are experiencing them. Such logs can help you to become more aware of incidents or thoughts that trigger your emotions and how you react to them. Do you remember, for example, the last time you cried or lost your temper? What was the catalyst? How did you feel about having the emotion? Did you feel relieved afterward or ashamed? Were others aware that you were having these feelings? Did you talk to anybody about the incident? These are the types of things you might note in an emotion log. You can also use the log to take note of your reactions to other people’s emotions, particularly those of your children. Each time you see your child angry, sad, or fearful, you can jot down notes about your own reaction.

Emotion logs can also be helpful for people who feel scared or anxious about their own emotional responses. That’s because the process of labeling an emotion and writing about it can help people define and contain the feeling. Emotions that once seemed mysterious and uncontrollable suddenly take on boundaries and limits. Our feelings become more manageable and they’re not as frightening anymore.

As you work with the emotion log, notice the kinds of thoughts, images, and language your feelings elicit. Look for insights in the metaphors you choose to describe your feelings. For example, do you sometimes see your anger or your child’s anger as destructive or explosive and therefore frightening? Or are you more likely to perceive it as powerful, cleansing, and energizing? What do such images tell you about your willingness to accept and work with negative emotions in your life? Do you notice attitudes or perceptions about emotion that you’d like to change?

Week of:

BEING AWARE OF CHILDREN’S EMOTIONS

Parents who are aware of their own emotions can use their sensitivity to tune in to their children’s feelings—no matter how subtle or intense. Being a sensitive, emotionally aware person, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that you’ll always find your child’s feelings easy to understand. Kids often express their emotions indirectly and in ways that adults find puzzling. If we listen carefully with open hearts, however, we can often de-code messages children unconsciously hide in their interactions, their play, their everyday behavior.

David, a father in one of our parenting groups, told how an incident

with his seven-year-old daughter helped him to understand the roots of her anger and showed him what she needed. Carly had been “in a dark mood” all day, he explained, picking fights with her four-year-old brother, taking offense at all sorts of imagined insults, including the classic: “Jimmy’s looking at me again!” With every interaction, Carly cast Jimmy as the villain, although Jimmy seemed to be doing nothing wrong. When David asked Carly why she was so angry at her easygoing sibling, his questions elicited only silence and tears. The more he probed, the more defensive Carly became.

At the end of the day, David went to Carly’s room to help her get ready for bed. There he found her pouting again. He opened her bureau to get her pajamas and found just one set clean—a tattered, outgrown pair with feet in the bottom. “Do you think these will fit?” he asked with a weak smile as he held them up for his lanky girl to see. David fetched a scissors, and together the two cut the feet off the pajamas so she could wear them. “I can’t believe how quickly you’re growing up,” he told her. “You’re getting to be such a big girl.”

Five minutes later, Carly joined the family in the kitchen for a bedtime snack. “She was like a different kid,” David remembers. She was chatty, upbeat. She even managed to crack a joke for Jimmy.

“Something happened during the business with the pajamas but I’m not sure what,” David told the other parents. After tossing it around the group, however, the answer was clearer to him. A serious, sensitive kid, Carly had always been jealous of charming, sweet-natured Jimmy. And for some reason, on that day in particular, she may have been needing reassurance of her own special place in the family. Perhaps she wanted to know that David loved her in a way that’s different from the way he loved Jimmy. Perhaps her father’s sweet acknowledgment that she’s growing up fast was just the ticket.

The point is, children—like all people—have reasons for their emotions, whether they can articulate those reasons or not. Whenever we find our children getting angry or upset over an issue that seems inconsequential, it may help to step back and look at the big picture of what’s going on in their lives. A three-year-old can’t tell you, “I’m sorry I’ve been so cranky lately, Mom; it’s just that I’ve

been under a lot stress since moving to the new daycare center.” An eight-year-old probably won’t tell you, “I feel so tense when I hear you and dad bickering over money,” but that may be what he’s feeling.

Among children about age seven and younger, clues to feelings are often revealed in fantasy play. Make-believe, using different characters, scenes, and props, allows children to safely try on various emotions. I remember my own daughter, Moriah, using her Barbie doll in this way at age four. Playing in the bathtub with the doll, she told me, “Barbie is really scared when you get mad.” It was her way of opening up an important conversation between us regarding what makes me angry, how my voice gets louder when I’m angry, and how that makes her feel. Grateful for the chance to talk it over, I assured Barbie (and my daughter) that I didn’t mean to scare her and that just because I get angry sometimes doesn’t mean that I don’t love her. Because Moriah was taking on the persona of Barbie, I talked directly to the doll and comforted her. This, I believe, made it easier for Moriah to continue talking about how she felt when I got angry.

Not all messages from children are this easy to decipher. Still, it’s common for children to act out their fears through games with serious themes like abandonment, illness, injury, or death. (Is it any wonder that children like to pretend they have the strength and magic of a Mighty Morphin Power Ranger?) Alert parents can take cues from the fears they hear expressed in their children’s play. Then, later on, they can address these fears and offer reassurances.

Hints of children’s emotional distress may also show up in behaviors such as overeating, loss of appetite, nightmares, and complaints of headaches or stomachaches. Children who have been potty-trained for some time may suddenly start wetting the bed again.

If you suspect that your child is feeling sad, angry, or fearful, it’s helpful to try to put yourself in their shoes, to see the world from their perspective. This can be more challenging than it sounds, especially when you consider how much more life experience you’ve had. When a pet dies, for example,

you

know that grief passes with time. But a child having this feeling for the first time may feel much more overwhelmed than you do by the intensity of the experience. While you can’t eliminate the differences in your experience, you

can try to remember that your child is facing life from a much fresher, less experienced, more vulnerable perspective.

When you feel your heart go out to your child, when you know you are feeling what your child is feeling, you are experiencing empathy, which is the foundation of Emotion Coaching. If you can stay with your child in this emotion—even though, at times, the feeling may be difficult or uncomfortable—you can take the next step, which is to recognize the emotional moment as a chance to build trust and offer guidance.

S

TEP

N

O

. 2: R

ECOGNIZING THE

E

MOTION AS AN

O

PPORTUNITY FOR

I

NTIMACY AND

T

EACHING

I

T IS SAID

that in Chinese the ideogram representing “opportunity” is encompassed in the ideogram for “crisis.” Nowhere is the linking of these two concepts more apt than in our role as parents. Whether the crisis is a broken balloon, a failing math grade, or the betrayal of a friend, such negative experiences can serve as superb opportunities to empathize, to build intimacy with our children, and to teach them ways to handle their feelings.

For many parents, recognizing children’s negative emotions as opportunities for such bonding and teaching comes as a relief, a liberation, a great “ah-ha.” We can look at our children’s anger as something other than a challenge to our authority. Kids’ fears are no longer evidence of our incompetence as parents. And their sadness doesn’t have to represent just “one more blasted thing I’m going to have to fix today.”

To reiterate an idea offered by one Emotion-Coaching father in our studies, a child needs his parents most when he is sad or angry or afraid. The ability to help soothe an upset child can be what makes us “feel most like parents.” By acknowledging our children’s emotions, we are helping them learn skills for soothing themselves, skills that will serve them well for a lifetime.

While some parents try to ignore children’s negative feelings in the hope that they will go away, emotions rarely work that way. Instead, negative feelings dissipate when children can talk about their emotions, label them, and feel understood. It makes sense, therefore,

to acknowledge low levels of emotion early on before they escalate into full-blown crises. If your five-year-old seems nervous about an upcoming trip to the dentist, it’s better to explore that fear the day before than to wait until the child is in the dentist chair, throwing a full-blown tantrum. If your twelve-year-old feels envious because his best friend got the position he coveted on the baseball team, it’s better to help him talk over those feelings with you than to let them boil over in a row between the two buddies next week.