Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis (221 page)

Authors: Mary A. Williamson Mt(ascp) Phd,L. Michael Snyder Md

Galactorrhea refers to any persistent discharge of milk or milk-like secretion from the breasts in the absence of a gestational event or beyond 6 months postpartum in a woman who is not nursing.

Overview

Galactorrhea needs to be distinguished from other forms of nipple discharge. Galactorrhea is usually manifested by bilateral milky nipple discharge involving multiple ducts. Green, yellow, bloody, or multicolored fluid should lead the clinicians to look for other causes of nipple discharge. When gross inspection does not permit the identification of the nipple discharge, microscopic examination can be helpful. Milk is rich in lipid content, and thus a fat stain is highly sensitive in confirming the diagnosis of galactorrhea.

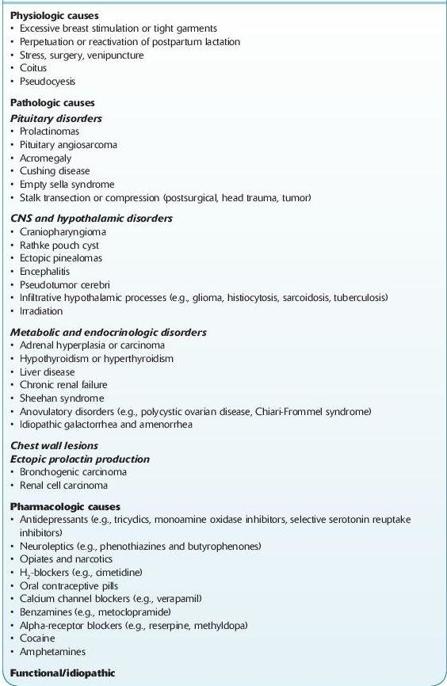

Common Causes (Table

6-6

)

I. Physiologic causes

A. Galactorrhea from perpetuation or reactivation of lactation. This accounts for the vast majority of galactorrhea cases. In general, prolactin levels, menses, and fertility are normal. Reactivation of pregnancy-related lactation may occur after a spontaneous first-trimester pregnancy loss, therapeutic abortion, or ectopic pregnancy.

B. Disorders of the chest wall. Although rare, chest wall injury from surgery such as mastectomy, trauma, infiltrating tumors, and herpes zoster eruptions can produce galactorrhea. Hyperprolactinemia may or may not be present. The mechanism for this milk formation is uncertain, but it may result from chronic neuronal stimulation from the breast to the hypothalamus. Other causes must be ruled out prior to attributing galactorrhea to this cause.

II. Pathologic causes

A. Pituitary tumors. The most important evaluation in a patient with galactorrhea is the consideration of a pituitary tumor.

B. Idiopathic galactorrhea with amenorrhea. Generally, the patients in this group have elevated prolactin levels and normal imaging. Possible mechanisms for this disorder include interference of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH), release in the hypothalamus by prolactin, alternation of pituitary sensitivity to LHRH, or interference with steroidogenic action of gonadotropins at the level of the ovary.

C. Anovulatory syndromes.

1. Chiari-Frommel syndrome. It is characterized by galactorrhea and amenorrhea that occurs more than 6 months postpartum in the absence of nursing and in the absence of a pituitary tumor. Approximately 50% of these women will resume normal menses over the next few months. A small minority may have occult microadenomas of pituitary, which may become clinically apparent with time.

2. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). It is characterized by obesity, oligomenorrhea, infertility, and hirsutism. Elevated prolactin levels may accompany this syndrome, thereby leading to galactorrhea.

D. Endocrinopathies

1. Hypothyroidism is a rare cause of galactorrhea. Prolactin levels may be normal or slightly elevated. Galactorrhea is corrected with restoration of euthyroidism.

2. Galactorrhea is a frequent finding in women with thyrotoxicosis. Serum prolactin is normal, and the mechanism of galactorrhea is unknown.

3. Cushing syndrome and acromegaly can be associated with galactorrhea. Workup for these conditions should be undertaken only if specific signs and symptoms are present.

E. Ectopic prolactin production. It is a very rare cause of galactorrhea, and other causes should be excluded first. Tumors that have been associated with ectopic prolactin production include renal cell carcinoma and bronchogenic carcinoma.

III. Pharmacologic causes

A. Galactorrhea associated with elevated prolactin levels. Most pharmacologic agents that cause prolactin release either block dopamine receptors (e.g., neuroleptics) or deplete dopamine in the tuberoinfundibular neurons (e.g., centrally acting alpha-blockers). All types of antidepressants can cause galactorrhea, but selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) do so more commonly than other antidepressants.

B. Galactorrhea associated with oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Both usage and discontinuation of OCPs can cause galactorrhea. The exact mechanisms are unknown. The abrupt cessation of estrogen and progesterone mimics withdrawal at the time of delivery and can trigger milk production. Estrogen at postmenopausal replacement dose is not associated with galactorrhea.

TABLE 6–6. Causes of Galactorrhea

Who Should Be Suspected?

Differential diagnosis of galactorrhea is broad. The goal is to identify the small number of women with pituitary adenoma or other space-occupying lesions as the cause of galactorrhea.

I. History:

A. Menstrual and reproductive history: Galactorrhea can be seen during pregnancy, including ectopic pregnancy, and in the immediate postpartum period. Hyperprolactinemia can lead to hypoestrogenemia, with amenorrhea and infertility. Higher levels of prolactin are associated with more significant menstrual derangements. Galactorrhea in men suggests a pathologic process and should always have an aggressive workup assessing for a pituitary adenoma and hypogonadism.

B. Medication history.

C. History of chest wall surgery, trauma, or herpes zoster eruption.

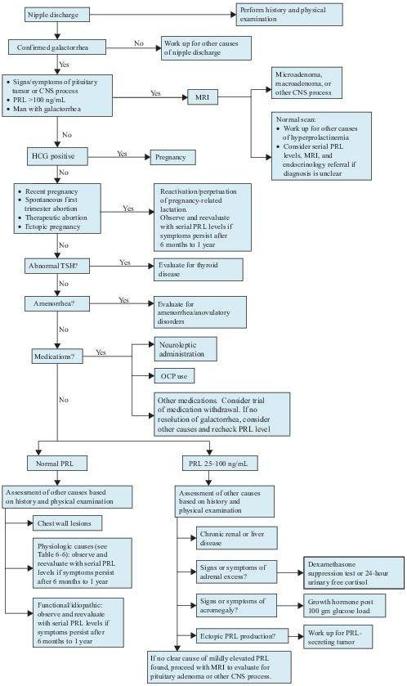

II. Physical examination (Figure

6-11

):

A. Eye examination: Check visual acuity and visual fields and examine the cranial nerves. Assess for symptoms of pituitary diseases such as cranial neuropathies (nerves III, IV, or VI), visual field deficits (bitemporal hemianopsia, optic chiasm, or optic nerve compression), or headache.

B. Breast and chest wall examination: Confirm galactorrhea; palpate for masses, scars, and eruption. Endocrine laboratory testing should be ordered without performing either breast examination or nipple stimulation.

C. Skin examination: Note abnormal skin texture (e.g., myxedema), striae, pigmentation, or hirsutism.

D. Endocrine examination: Assess for thyroid dysfunction, stigmata of Cushing syndrome (striae, buffalo hump, and central obesity), and acromegaly. Abnormalities of temperature, thirst, and appetite regulation suggest hypothalamic disease.

E. Pelvic examination: Check ovarian and uterine sizes for causes of amenorrhea and anovulation.

Figure 6–11

Algorithm for the workup of galactorrhea. CNS, central nervous system; HCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OCP, oral contraceptive pill; PRL, prolactin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Laboratory Findings

1. Serum prolactin: The concentrations may increase slightly during sleep, strenuous exercise, occasionally emotional or physical stress, intense breast stimulation, and high-protein meals. Therefore, a slightly high value should be confirmed before the patient is considered to have hyperprolactinemia. Mildly elevated prolactin levels should prompt investigation for a tumor, even if no other clear cause for the hyperprolactinemia is identified or if symptoms and signs of pituitary and central nervous system (CNS) processes are present. Sample dilutions may be needed in patients with strong suspicion for hyperprolactinemia, but normal or low level of plasma prolactin levels.