Data Mining (108 page)

Authors: Mehmed Kantardzic

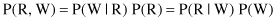

and therefore

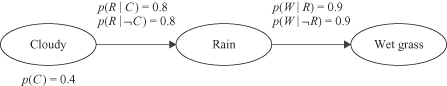

Let us include now more complex problems, and the more complex BN represented in Figure

12.37

. In this case we have three nodes, and they are connected serially, often called head-to-tail connections of three events. Now an additional event, “Cloudy,” with yes and no values is included as a variable at the beginning of the network. The R node blocks a path from C to W; it separates them. If the R node is removed, there is no path from C to W. Therefore, the relation between conditional probabilities in the graph are given as: P(C, R, W) = P(C) * P(R|C) * P(W|R).

Figure 12.37.

An extended causal graph.

In our case, based on the BN in Figure

12.37

, it is possible to determine and use “forward” and “backward” conditional probabilities as represented in the previous BN. We are starting with:

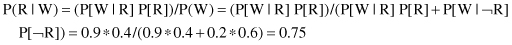

Then, we may use Bayes’ rule for inverted conditional probabilities:

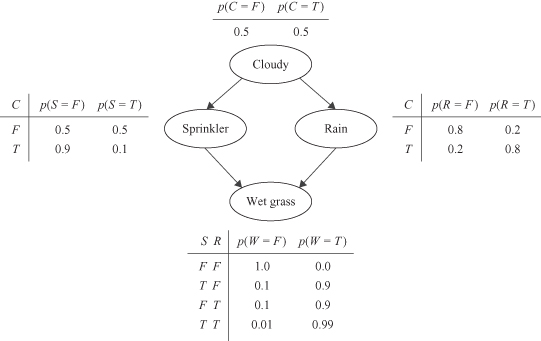

More complex connections may be analyzed in BN. The following Figure

12.38

shows the graph structure and the assumed input parameters.

Figure 12.38.

Four-node architecture of a Bayesian network.

The parameters of a graphical model are represented by the conditional probability distributions in a form of CPT tables for each node, given its parents. The simplest form of a formalized distribution, a CPT table, is suitable when the nodes are discrete-valued. All nodes in Figure

12.38

are represented with a discrete set of states, and corresponding CPTs. For example, “Sprinkler” node (S) may be “on” and “off,” and is represented in the table with T and F values. Sprinkler CPT table is generated including input discrete values for node the “Cloudy” (C). Many algorithms for BN analysis may be expressed in terms of the propagation of probabilities through the graph.

All probabilistic models, no matter how refined and accurate, Bayesian included, describe a distribution over possible observed events, but say nothing about what will happen if a certain intervention occurs. For example, what if I turn on the sprinkler? What effect does that have on the season, or on the connection between wetness and slipperiness? A causal network is a BN with the added property that the parents of each node are its direct causes. In such a network, the result of an intervention is obvious: The sprinkler node is set to “on” and the causal link between the season and the sprinkler is removed. All other causal links and conditional probabilities remain intact. This added property endows the causal network with the capability of representing and responding to external or spontaneous changes. For example, to represent a disabled sprinkler in the story of Figure

12.38

, we simply delete from the network all links incident to the node Sprinkler. To represent the policy of turning the sprinkler off if it rains, we simply add a link between Rain and Sprinkler. Such changes would require much greater remodeling efforts if the network were not constructed along the causal direction. This remodeling flexibility may well be cited as the ingredient that manages novel situations instantaneously, without requiring training or adaptation of the model.

12.6 PRIVACY, SECURITY, AND LEGAL ASPECTS OF DATA MINING

An important lesson of the Industrial Revolution was that the introduction of new technologies can have a profound effect on our ethical principles. In today’s Information Revolution we strive to adapt our ethics to diverse concepts in cyberspace. The recent emergence of very large databases, and their associated data-mining tools, presents us with yet another set of ethical challenges to consider. The rapid dissemination of data-mining technologies calls for an urgent examination of their social impact. It should be clear that data mining itself is not socially problematic. Ethical challenges arise when it is executed over data of a personal nature. For example, the mining of manufacturing data is unlikely to lead to any consequences of a personally objectionable nature. However, mining clickstreams of data obtained from Web users initiate a variety of ethical and social dilemmas. Perhaps the most significant of these is the invasion of privacy, but that is not the only one.

Thanks to the proliferation of digital technologies and networks such as the Internet, and tremendous advances in the capacity of storage devices and parallel decreases in their cost and physical size, many private records are linked and shared more widely and stored far longer than ever before, often without the individual consumer’s knowledge or consent. As more everyday activities move online, digital records contain more detailed information about individuals’ behavior. Merchants’ record data are no longer only on what individuals buy and how they pay for their purchases. Instead, those data include every detail of what we look at, the books we read, the movies we watch, the music we listen to, the games we play, and the places we visit. The robustness of these records is difficult to overestimate and is not limited to settings involving commercial transactions. More and more computers track every moment of most employees’ days. E-mail and voice mail are stored digitally; even the content of telephone conversations may be recorded. Digital time clocks and entry keys record physical movements. Computers store work product, text messages, and Internet browsing records—often in keystroke-by-keystroke detail, they monitor employee behavior.

The ubiquitous nature of data collection, analysis, and observation is not limited to the workplace. Digital devices for paying tolls, computer diagnostic equipment in car engines, and global positioning services that are increasingly common in passenger vehicles record every mile driven. Cellular telephones and personal digital assistants record not only call and appointment information, but location as well, and transmit this information to service providers. Internet Service providers (ISPs) record online activities; digital cable and satellite record what we watch and when; alarm systems record when we enter and leave our homes; and all of these data are held by third parties. Information on our browsing habits is available to both the employer and the ISP. If an employee buys an airline ticket through an online travel service, such as Travelocity or Expedia, the information concerning that transaction will be available to the employer, the ISP, the travel service, the airline, and the provider of the payment mechanism, at a minimum.

All indications are that this is just the beginning. Broadband Internet access into homes has not only increased the personal activities we now engage in online but also created new and successful markets for remote computer backup and online photo, e-mail, and music storage services. With Voice over Internet Protocol (IP) telephone service, digital phone calls are becoming indistinguishable from digital documents: Both can be stored and accessed remotely. Global positioning technologies are appearing in more and more products, and Radio Frequency Identification Tags are beginning to be used to identify high-end consumer goods, pets, and even people.

Many individuals are unaware of the extent of the personal data stored, analyzed, and used by government institutions, private corporations, and research labs. Usually, it is only when things go wrong that individuals exercise their rights to obtain these data and seek to eliminate or correct it. For many of those whose records are accessed through data mining, we do not know it is happening, and may never find out because nothing incriminating is signaled. But we still know that data mining allows companies to accumulate and analyze vast amounts of information about us, sufficient perhaps to create, with the help of data mining, what some have called personality or psychological “mosaics” of the subjects. One result of the entry into the information age is that faceless bureaucrats (in a company, in government, everywhere) will be able to compile dossiers on anyone and everyone, for any reason or for no reason at all. The possibility, even if slim, that this information could somehow be used to our detriment or simply revealed to others can create a chilling effect on all these activities.

Data and the information derived from those data using data mining are an extremely valuable resource for any organization. Every data-mining professional is aware of this, but few are concentrated on the impact that data mining could have on privacy and the laws surrounding the privacy of personal data. Recent survey showed that data-mining professionals “prefer to focus on the advantages of Web-data mining instead of discussing the possible dangers.” These professionals argued that Web-data mining does not threaten privacy. One might wonder why professionals are not aware of or concerned over the possible misuse of their work, and the possible harm it might cause to individuals and society. Part of the reason some professionals are not concerned about the possible misuse of their work and the potential harm it might cause might lie in the explanation that “they are primarily technical professionals, and somebody else should take care of these social and legal aspects.” But sensible regulations of data mining depend on the understanding of its many variants and its potential harms. Therefore, technical professionals have to be a part of the team, often leading, which will try to solve privacy challenges.